Strathcona Provincial Park, established in 1911, has not always been the serene and majestic wilderness area it is known as today. Current visitors might not be aware that mining and logging still took place in the park well into the 1980s.

With A Journey Back to Nature: A History of Strathcona Provincial Park, just published by Heritage House, historian Catherine Marie Gilbert unearths the complex origins of B.C.’s first provincial park. She details the century-long effort to define, access, preserve, develop and exploit the area on Central Vancouver Island.

In this excerpt, Gilbert, whose master’s thesis focused on the unique environmental history of the park, lays out the early and ongoing struggles to build access roads for park visitors.

^

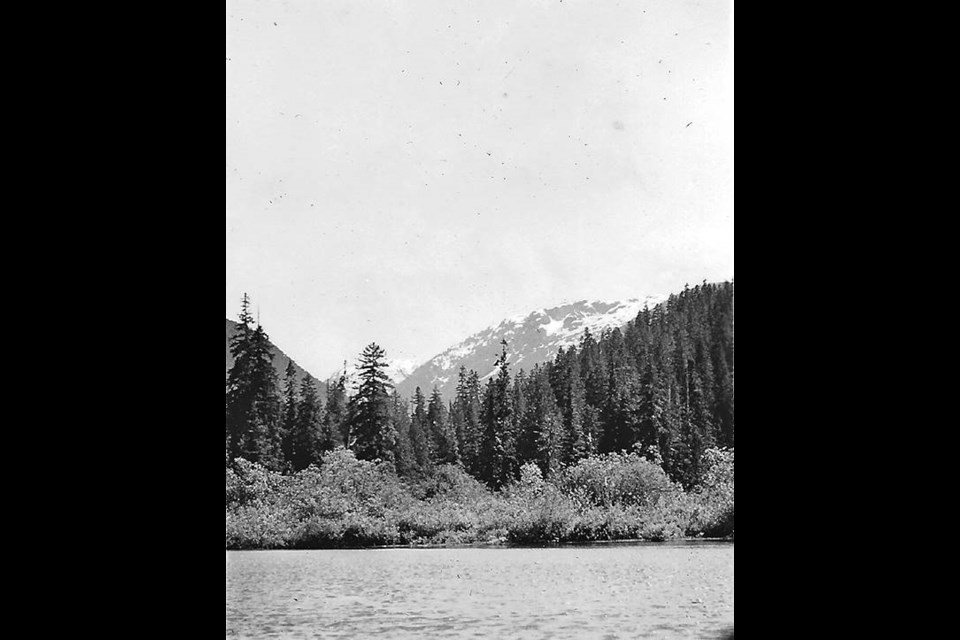

The industry topmost in the minds of the creators of Strathcona Provincial Park was tourism. The future of the park looked promising in 1911, when premier Richard McBride’s Conservative government established it based upon reports by early explorers of its stunning vistas, rugged mountains, jewel-like lakes and magnificent waterfalls.

There were lofty plans to transform this new park into the next Banff, with visions of rail lines extending 275 kilometres from Victoria to this remote location, and first-class accommodation awaiting travellers.

A significant obstacle to developing the park as a tourist destination was that until the late 1950s, it was challenging for visitors to access the park by automobile. Forestry companies had opened up much of the area with logging roads, but they were not suitable for the average car.

The McBride administration hired Seattle engineer Reginald H. Thomson to develop the park as a tourist mecca, due to his experience in large projects in the United States.

His first task as Strathcona Park engineer was to “secure access to, and into, the rugged, isolated park.” At that time, the points of access to the park, all difficult, were from Alberni to the southwest, the Bedwell Valley to the west, Gold River and Campbell River.

Thomson at first envisioned access from Alberni, which had the advantage of road access to Victoria, but once he undertook the trip himself, he recognized the difficulty and abandoned the idea.

The provincial government undertook building a road west from Campbell River to the Buttle Lake region in 1912. Surveyor William J.H. Holmes in 1913 described the route:

“A wagon road, at present a very poor one, runs from Campbell River in a westerly direction about 7 miles to McIvor Lake, and thence around this lake for another two miles to Forbes Landing at the east end of Lower Campbell Lake; thence it continues as a horse-trial via Gooseneck Lake along Upper Campbell Lake and Upper Campbell River to Buttle Lake, within park limits. Along this trail a first-class road is at present under construction, which it is expected will be completed in about two years, giving easy access to Buttle Lake for those on pleasure bent.”

R.H. Thomson’s 1914 progress report concerning planning for the park contains details of the road construction, and his enthusiasm for the undertaking is plain to see when he remarks that as all roads lead to Rome, “all roads lead to Strathcona Park.”

Eric Sismey, an early surveyor on the road referred to by Holmes, described his journey to the surveyor’s camp at Gooseneck Lake, marvelling at the enormous trees he passed on the way.

While Holmes was “blazing the park boundaries,” Sismey’s group surveyed the proposed route along Lower Campbell and Upper Campbell Lakes to Buttle Lake, and developed pack horse trails along the Campbell River. Once the existing horse trail became a serviceable road, his crew forged a trail into the Park that extended past the end of the surveyed road, until November rains prohibited further work.

By 1915, the road itself was completed to within about 11 miles of the park’s entrance. At 20 miles long, the road terminated near Jasper Sutherland’s provisioning camp on the shores of Upper Campbell Lake, from where it was possible to get a boat and travel by water to the end of Upper Campbell Lake, then complete the trip to the park by hiking in nine miles to Buttle Lake.

Despite the growing interest in visiting the park among those with the income and leisure to undertake the journey, construction on the highway ceased in 1915, a year after the First World War broke out. Funds were diverted away from the project toward the war effort, and a lack of manpower, as road crews enlisted or were conscripted, further inhibited progress.

It is interesting to speculate whether finances from timber sales would have encouraged officials to push the road to completion. Historian William Wilson notes that resentment of Thomson’s non-Canadian status as well as his high salary contributed to his decision to return to the U.S. in 1915.

The dream of using the park to promote tourism on Vancouver Island did not die altogether, despite the war. A deputation of Island civic elites met with Premier McBride and Public Works Minister Thomas Taylor on November 1915 in Victoria. Some expressed hopes that with tourists cut off from Europe because of the conflict, the North American continent would become an inviting tourist destination, offering soothing wilderness respite from the vagaries of war.

Herbert Cuthbert of the Tourist Association of Victoria submitted figures to show that tourism had become an industry, and the expansion of rail construction in the Pacific Northwest of the United States was bound to benefit Vancouver Island.

He believed it was critical for the Island to expand its own rail transportation system beyond Nanaimo, as well as to have road work completed in the north central part of the Island.

McBride and Taylor made it clear, however, that there would be no further development of Strathcona Park “as would put that area in such shape as to make it available for tourists and warrant advertising it as a tourist resort. The need of conserving the financial resources of the Province to meet urgent expenditures in other directions precluded any considerable outlay on Strathcona Park.”

With the war over in 1919, groups such as the Island Automobile Association were lobbying for the opening up of roads to such destinations as Strathcona Park.

In that same year, Campbell River was at last connected to Victoria by road via Courtenay. There was now an alternative to having to take a coastal steamer to get to Campbell River, but the journey to the park was a distance of about 30 miles, and since stoppage of work on the road to the park in 1915, access from Campbell River itself had not been improved upon.

The road completed by the government in 1915 had clearly deteriorated in the intervening years, since the entire route from Forbes Landing to where the road ended at Upper Campbell Lake was driveable at that time.

Indeed, a 1915 government report predicted that if work on the road was delayed, it would inevitably become obliterated once subjected to the region’s heavy rains.

The Courtenay Board of Trade and Associated Boards of Trade of Vancouver Island, citing the increasing volume of tourist traffic in the region, continued to urge the opening up of the park.

Their 1924 Resolution observed that “to carry the road through to Strathcona Park would cost a considerable amount of money; but to finish it to Upper Campbell Lake is comparatively inexpensive and should be done at once.”

Again in 1925, the local Board of Trade argued that since so much money had already been spent on constructing the Strathcona Park road, and since such a road would be an asset to the province, it should be completed regardless of cost.

Lands Minister T.D. (Duff) Pattullo responded that the province had no immediate interest in constructing a road to Strathcona Park.

A year later, the Daily Colonist wondered if the government would develop Strathcona or cancel its designation as a park.

Local interests continued to lobby for the improvement of these roads west from Campbell River and asked for completion of a road to the Buttle Lake entrance of the park.

When the road was finally completed and improved upon, so that the public could easily drive from Campbell River to Buttle Lake, then down the east side of Buttle Lake to its southern end, it was not the Department of Public Works that financed the projects.

Instead, the B.C. Power Commission built sections of the road in 1951 and 1958, followed by Western Mines Ltd., which in 1965 completed the road, illustrating the provincial government’s waning interest in tourism and growing interest in opening up the park to industry.