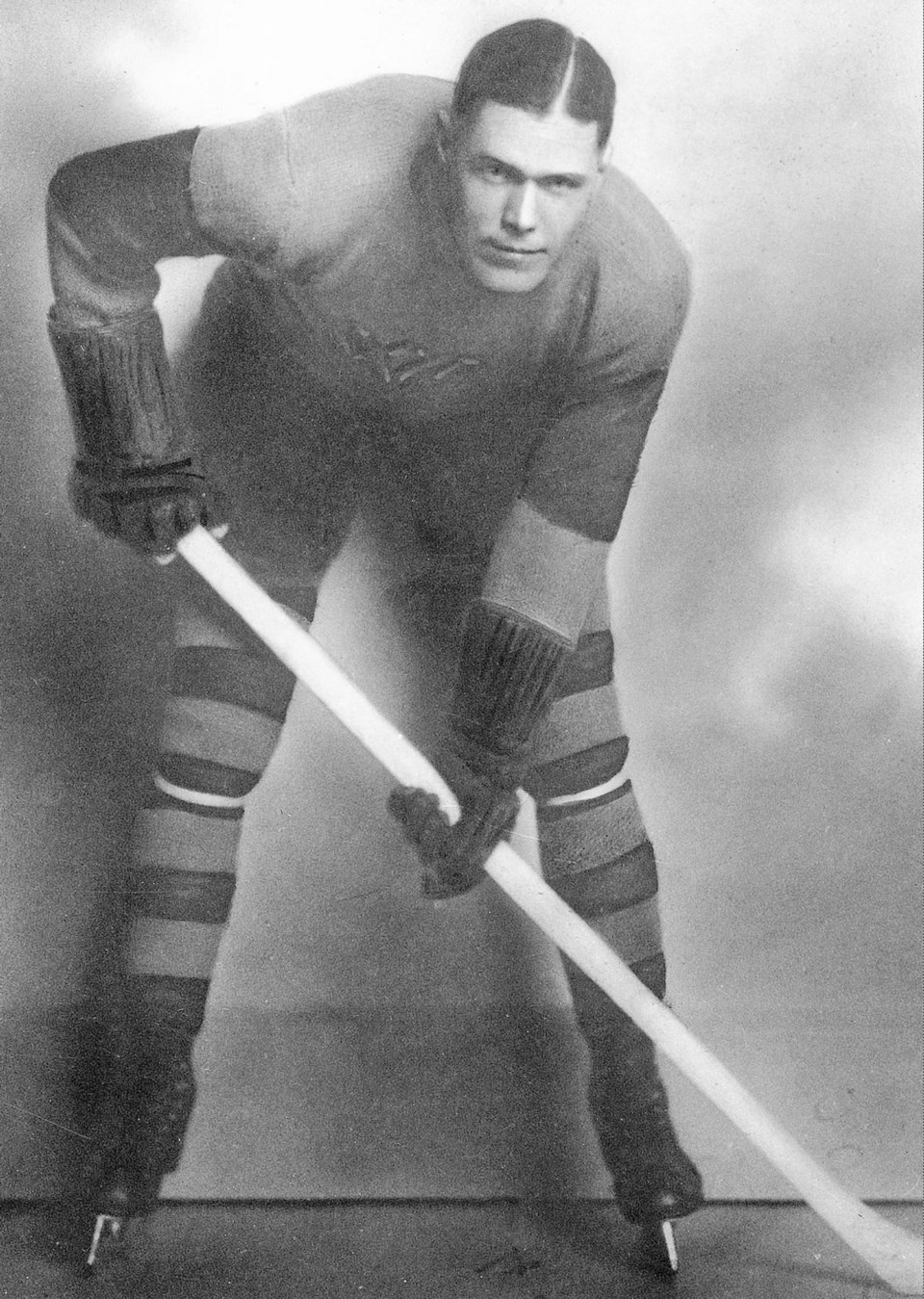

Winnipeg-born Frank Fredrickson was an all-star hockey player, Olympic gold medallist, gifted violinist and valued airman with the 223rd Battalion/Royal Flying Corps/RAF, in which he served from 1916 to 1919. His story is one of 30 profiled in a new book about the impact of war during the early years of pro hockey in Canada.

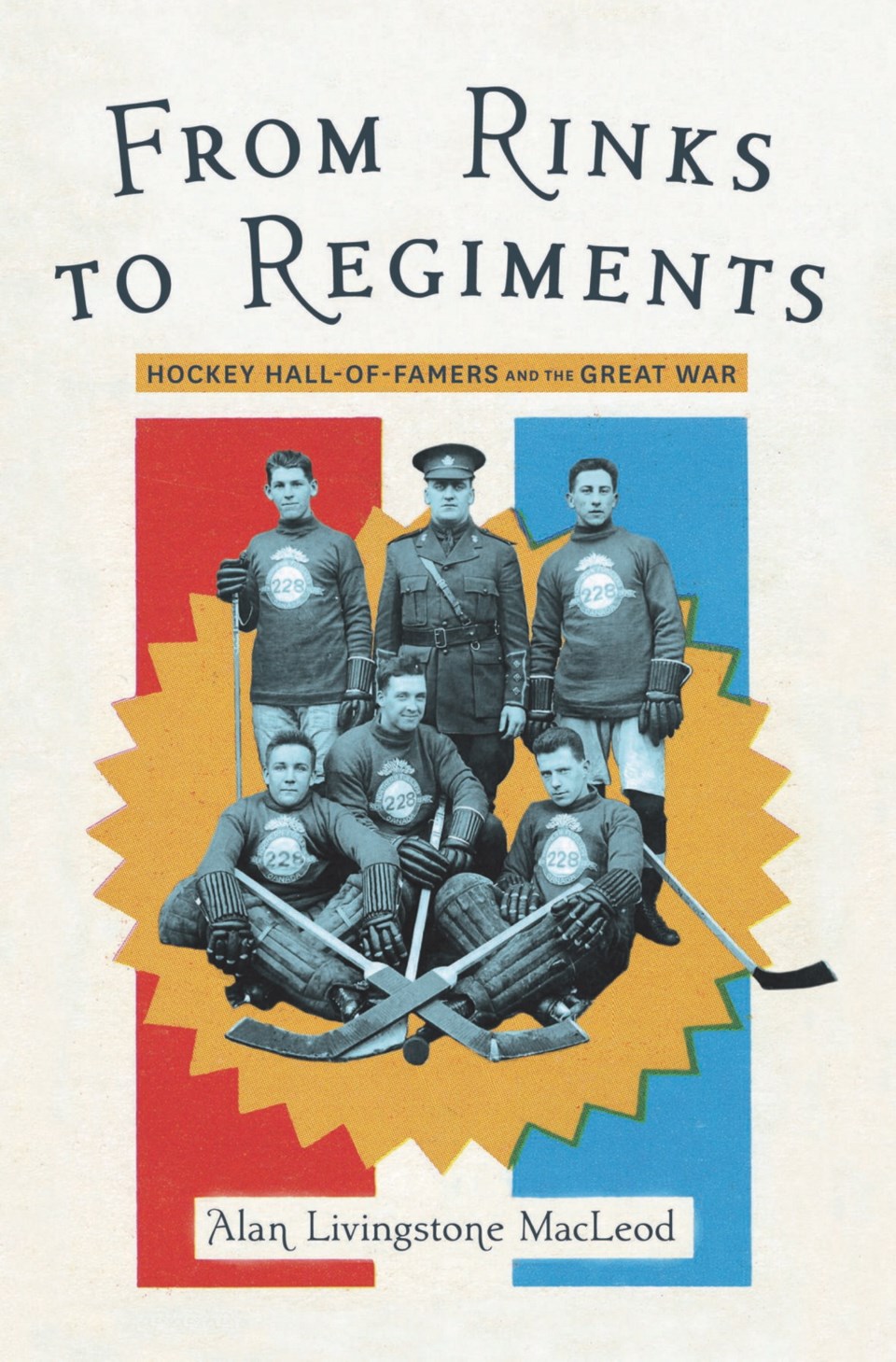

©Alan Livingstone MacLeod, Heritage House, 2018

His blue eyes and fair complexion notwithstanding, Sigurdur Frank Fredrickson experienced discrimination in his early years in Winnipeg. Born in Canada, Fredrickson was the son of parents who had immigrated to Manitoba from Iceland toward the end of the 19th century. He spoke only Icelandic before he went to school.

They ate different food, went to a different church and spoke accented English, but Fredrickson and his friends were perfectly Canadian in their enthusiasm for the game of hockey. Shunned by lads of other ethnic origins, the Icelanders organized themselves into hockey teams of their own. Soon enough, they were beating everyone in sight.

By age 18, in 1913, Fredrickson was the leading light of the Winnipeg Falcons, almost all of them ethnic Icelanders. That year, their first in the Independent Hockey League, the Falcons finished last. It took only a year for them to reverse their fortunes: In 1914-15 they won the league championship.

In February 1916, Fredrickson — known to all by now as Frank, rather than Sigurdur — volunteered for the Canadian Expeditionary Force. He enlisted in the 196th Battalion, but soon moved to the 223rd Battalion (Canadian Scandinavians). Enrolled in the University of Manitoba at the time, he listed his “trade or calling” as student.

The 223rd embarked from Halifax in early May 1917, arriving in Liverpool on May 15. It didn’t take long before Frederickson decided that the life of a foot soldier in an infantry battalion might not be the best option on offer in King George’s combined forces. He decided to become an airman and, together with two fellow Falcons, managed to get a transfer to the Royal Flying Corps.

Aboard the troopship Aragon, the Icelanders departed Taranto, Italy, for Alexandria, Egypt, to do their air training. Shortly after their safe passage, the Aragon was torpedoed by a German U-boat, which resulted in the loss of more than 600 lives.

While learning to fly at the British airbase in Aboukir, the Winnipeggers managed to squeeze more than a little fun into their days. Fredrickson took a camera wherever he went; photographs taken during his time in Aboukir show him at the Sphinx, riding a camel and wearing his airman uniform but with an Egyptian fez on his head. There is a standard feature in every image — Fredrickson’s beaming smile.

In May, his flight training successfully completed, Fredrickson departed Alexandria for the return voyage across the Mediterranean. He had avoided disaster on his outward journey but he was unluckier this time. On May 28, the transport ship he was travelling on, the Leasowe Castle, was struck by a German torpedo. Ninety-two men were lost.

Fredrickson was a highly accomplished violinist. As men fled the sinking Leasowe Castle, he put his cherished violin in the hands of a lifeboat captain. There was no room for Fredrickson, but once in the water he managed to scramble into a different lifeboat. The violin was saved, and so was Fredrickson.

Once in Britain, he was posted to a Royal Air Force airbase in Gullane, Scotland. The average life expectancy of a fighter pilot operating over the Western Front was less than 20 hours of flying time, but Fredrickson struck it lucky again. Because he was a talented flier and able communicator, his commanders decided the best use the RAF could make of him was as a flying instructor and test pilot.

He flew an array of machines: the Sopwith Camel and Pup, Bristol Fighter, Nieuports and the superb new Royal Aircraft Factory scout, the SE5A.

As he had done at Aboukir, Fredrickson made a point of balancing duty with fun. Charmed by a young Edinburgh woman, Fredrickson decided to do some “sensational flying” over a tea party she had arranged. On returning to Gullane, the engine of his SE5A failed. He crash-landed, sustaining multiple and widespread cuts, contusions and bruises. But he survived again.

Gullane was close enough to Edinburgh that Fredrickson was able to take frequent advantage of the city’s amenities, and he attended many theatrical events and concerts. He was a capable photographer and took impressive images of Edinburgh landmarks and kept a diary recording detailed impressions of the city and the urban attractions he liked best. While flying out of Gullane, he experienced the occasional hair-raising landing but suffered nothing worse than bruises and lacerations.

Nov. 11 brought the end of the war. Fredrickson had come through.

He returned to Canada in time to resume playing for the Winnipeg Falcons in 1919-20. He hadn’t lost a step, once again leading the league in scoring with 23 goals in just 10 games. After establishing themselves as the best team in Manitoba, the Falcons took on the University of Toronto for the Canadian amateur championship — and the Allan Cup. They won easily, outscoring U of T 11-5 in a two-game series.

On the strength of that victory, the Falcons earned the right to represent Canada in the first Olympic Games that included hockey. Fredrickson and the Falcons travelled to Antwerp, Belgium, for the 1920 Games. In the quarter-final against Czechoslovakia, the Canadians won easily, 15-0. The semifinal was tougher, as they were facing Moose Goheen and his fellow Americans, but the Canadians won, 2-0.

The gold medal game against Sweden was a cakewalk: a 12-1 victory.

Iceland could take as much pride in the gold medal as Canada did: the Canadians were almost entirely sons of Icelandic immigrants, men named Johannesson, Halderson, Fridfinnson and Fredrickson. The boys with odd-sounding names had turned themselves into world champions.

As this great adventure was drawing to a close, Fredrickson was offered another. He learned that an Icelandic company was looking for an ethnic Icelander to introduce people to flying. Fredrickson seized the opportunity to travel to the land of his forebears and take Icelanders into the air in a 504K Avro. While in Iceland, he crash-landed — and survived — again.

One more great adventure lay in store. Mulling his options at age 26, Fredrickson was contemplating a career in the Royal Canadian Air Force. Then Lester Patrick made him an offer he couldn’t refuse: $2,500 to play a 24-game season with his Victoria club in the PCHA. Fredrickson agreed.

What followed was a storied six-year career in British Columbia’s capital. The pride of Icelandic Winnipeg led his club in scoring all six years and was a league all-star in all but one of those years. In 1922-23, he scored 39 goals and added 16 assists to win the league scoring title by 18 points over the second-best scorer. In 1925, he led the Victoria Cougars to a Stanley Cup victory over the Montreal Canadiens. It was the last time a club not part of the NHL would have its name inscribed on the Cup.

Fredrickson had one more kick at the cup the following year, 1925-26, but this time the Cougars lost to the Montreal Maroons. It was a finale for the league too; the Western Hockey League folded after the Stanley Cup series.

In 1926-27, Fredrickson and several of his Victoria teammates found themselves reconstituted as the Detroit Cougars of the NHL. Fredrickson reached another pinnacle: earning $6,000 for the ’26-27 season, he was the highest-paid player in pro hockey. He played only 16 games in Detroit before he was parcelled up and shipped to the Boston Bruins for Gordon Keats.

In his 30s by this time, Fredrickson would not shine in the NHL as brightly as he had done in Victoria. He played three years in Boston and liked his situation there, but in 1928, he was dealt to the Pittsburgh Pirates. He played two seasons there before returning to Detroit for one final go-round in 1930-31. By age 35, he was done.

In 1929-30, while still a player, Fredrickson had taken over as Pittsburgh coach. The new role was not rewarding: the Pirates won only five times in a 44-game schedule and finished 21 points behind next-worst Detroit. The following year, the franchise was moved to Philadelphia and Fredrickson was replaced as coach by none other than Cooper Smeaton.

In 1933, Fredrickson accepted a job as coach of Hobey Baker’s alma mater, Princeton University. There was another Princeton rookie that year, a physicist-mathematician who had decided that Adolf Hitler’s Germany was no longer a tolerable place to call home. The learned man had something in common with Fredrickson: he, too, was an accomplished violinist. They struck up a friendship and often walked to campus together. The other violinist? Albert Einstein.

When the Second World War erupted in 1939, Fredrickson stepped forward again. He joined the RCAF, commanded an air force flying school, and coached an air force hockey team, the Sea Island Flyers, from 1940 until 1945. After the war, he took over as coach of the University of British Columbia and was highly regarded by the Thunderbirds who played for him.

Another member of the Hockey Hall of Fame class of 1958, Frank Fredrickson lived long and well. He died two weeks short of his 84th birthday, in Vancouver, in 1979.

• All are welcome to attend a free talk by author Alan MacLeod at 2 p.m. on Saturday, Nov. 24, at the Victoria Public Library Central Branch.