During the 1860s, the British engraver Frederick Whymper sketched his way through the Pacific Northwest as an artist-for-hire with survey expeditions to B.C., Alaska and Siberia. In this excerpt from his biography of Whymper, Peter Johnson shares impressions from the artist’s travel journals of the Cowichan Valley region, about 1864.

In early June of 1864, Whymper was formally offered the position as official artist for the Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition. Whymper began recording what he had learned of Vancouver Island’s history almost immediately. He wrote: “In 1864, but few of the settlers in this colony had penetrated 10 miles back from the towns and settlements of the east coast.” He had learned of the previous jaunts of Capt. Richards, Commander Mayne, and Messers Pemberton and Pearce, and wanted to know more; they “had already made very interesting journeys into the interior, yet the results of their explorations were little known.”

It didn’t take long, however, for Whymper to discover that the expedition was little more than a government-supported ruse to search for “homegrown” Island gold that might shake Victoria from its economic doldrums. He wrote: “Victoria had been built and sustained by the [mainland] British Columbia gold mines, and fluctuated with them.”

Though the Fraser River gold rush of 1858 had produced unprecedented growth in Victoria, its city lots increasing in value 40 times in less than a year, Victoria’s boom-time population of 30,000 soon plummeted. By 1860, most of the miners had given up panning and wandered, defeated, back to America.

With Victoria’s Hudson’s Bay Company outpost essentially defunct, and local mining suppliers rapidly going broke, the economic outlook of the city had once again become bleak. By 1863, Victoria was facing yet another recession.

In April of 1864, Gov. Arthur Edward Kennedy visited the gold diggings on Goldstream Creek, just west of Victoria. He, too, knew that Victoria was sustained largely by the mining activity on the mainland, so he readily backed a plan for an “official mapping survey” of the unexplored interior of Vancouver Island. Under that pretext, the survey would prospect for Vancouver Island gold and help Victoria achieve its hoped-for economic independence. The success of the expedition was so certain that Kennedy vowed to match public donations for the venture two to one.

The committee’s makeup hardly hid the obvious. Committee chairman Selim Franklin was a local auctioneer and land agent who had made his money on the gold miners, both in San Francisco and in Victoria; committee member Dr. John Ash was later made B.C.’s first minister of mines; and committee member “Major” John Downie had already garnered a considerable reputation as a prospector. Other committee members were surveyors, botanists, merchants and naval officers, but their “real” job, as the governor understood it, was clear.

With a “God’s speed” send-off from Kennedy, the expedition left Victoria on the Royal Navy gunboat HMS Grappler on June 7, 1864, bound for Cowichan Bay. Cautious yet affable, Whymper soon befriended the Grappler’s master, Captain Verney, “an ardent promoter of the proposed explorations.” Verney showed the cockney underling “much kindly courtesy.”

Whymper wrote: “On arrival at Cowichan Bay, we landed at the pretty little settlement of Comiaken, a place which boasts a Roman Catholic mission and several farms and settlers’ houses. In one of the latter we enjoyed so much hospitality that it was a serious question whether some of us would not stop there and let our travels end where they had begun!” Such drinking and partying were common in all of the settlements Whymper visited on the frontier. With only a few sanctimonious missionaries about, British civility and decorum, especially when the liquor ran freely, soon evaporated.

At Comiaken, the expedition hired an elderly chief, Kakalatza, who acted as their guide up the Cowichan River to Cowichan Lake. Kakalatza exploited his high status as a “tyhee” by slave trading and dressing as much as possible like the trim Royal Navy officers he had once seen at Cowichan Bay. The best he could manage, however, was to wear “a battered chimney-pot hat, given to him by some settler.” That hat became Kakalatza’s totem, and he simply refused to go anywhere without it or the box he kept it in. “Every night afterwards he carefully deposited his beaver in it, before retiring to his blankets.”

Whymper was rapidly loosening up and beginning to appreciate the foibles of the human condition. His growing sympathy toward the local people would soon be reflected in his art.

A one-armed French-Iroquois man named Tomo also joined the group at Comiaken. Tomo had travelled with surveyor general J.D. Pemberton in 1857 when he made a preliminary reconnoitre of the interior of Vancouver Island via the Nitinat River. As a guide, Tomo was invaluable. Not only was he an excellent marksman, but he could also speak any number of Indigenous dialects. Whymper noted that “when drunk, he was a devil.”

Tomo was paid $50 per month, while Whymper, along with most other members of the party, received $60. The other Indigenous members of the crew, despite their fear of being kidnapped, desperately needed the work and were hired as porters. They were paid much less.

On June 9, “after a ‘hyas wa-wa’ (big talk),” the expedition’s leader, Robert Brown, was able to hire a large canoe. Whymper wrote that Brown put “the larger part of the stuff therein and sent it up the Cowichan River in the charge of one white man of our party and several Indians. The larger of us proceeded by land direct to the village of Somenos, where we found several large lodges or rancheries,” as they were termed in the colony.

By June 11, after making a series of small portages, the party camped for two days at a place called Qualis, a natural clearing on the Cowichan River. Appreciative of a day’s rest on the Sabbath, the group turned to organizing stores, arranging tents, washing and hunting. On June 13, as the canyons of the Cowichan began to appear, they found respite from a continuous downpour by holing up in two deserted lodges. Whymper sketched the sodden explorers sleeping in one lodge, stretched out on abandoned Indigenous mats.

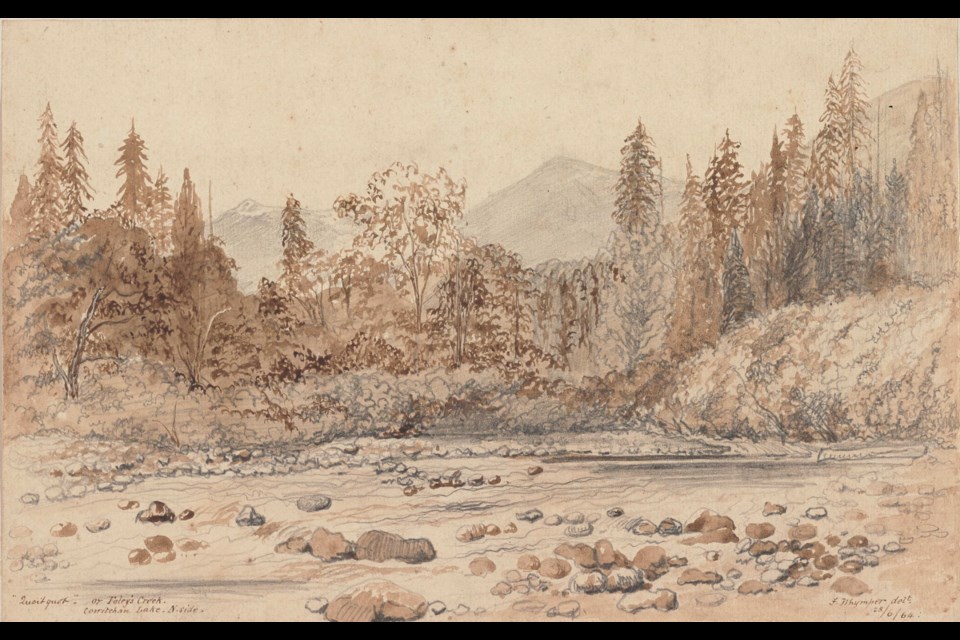

By the third week of June in 1864, the party had followed the Cowichan River upstream to a large lake. Whymper wrote: “The river was a succession of ‘riffles,’ or rapids — small and large — alternating with comparatively quiet water. … We found the banks thickly timbered, and where the Douglas pine, spruce and hemlock had grown under favourable circumstances, the place resembled a beautiful park; but for the most part it was a tangle of underbrush, mingled with fallen logs in all stages of decay, and woods in all degrees of luxuriance.”

Whymper noted that massive logjams occurred at almost every bend. Ever business-minded, he considered the idea of an industry that collected the rosin and turpentine from living trees (much like the sap from the sugar maple) growing in the bush, as was the case he had heard of in the forests of Oregon. He noted happily that such an enterprise in America created quite a profit.

Whymper discovered that the Cowichan people weren’t particularly anxious to be engaged as porters for the expedition: “The natives were drying fish and clams on strings hanging from the rafters of their dwellings, and were by no means anxious to engage in our service. … [T]hey lived so easily, getting salmon, deer and beaver meat in abundance, and consequently were indifferent to anything but extremely high pay.”

As well, they were afraid. Whymper wrote of “their fear of the surrounding tribes, especially those of the west coast, ” which was well-founded. Those tribes would occasionally “kidnap ‘unprotected males,’ and carry them off as slaves.” For most Cowichan Bay natives, any foray into alien territory farther west was extremely dangerous.

Author Peter Johnson will give a free talk on the life of Frederick Whymper at Bolen Books at 7 p.m. on Monday, Nov. 12.

A Not-So-Savage Land: The Art and Times of Frederick Whymper, 1838-1901, by Peter Johnson. Heritage House, 2018