Salt Spring Island naturalist, artist and author Briony Penn has spent decades studying the flora and fauna of the West Coast. In her new book, A Year on the Wild Side, she shares her unique perspectives — and enchanting illustrations — on the social and natural history of more than 98 plant and animal species found on the coast. In the following excerpts, she shares her observations about the springtime migration of grey whales, and the oft-hidden Calypso Orchid.

Grey Whales: Where the Sea Breaks Its Back

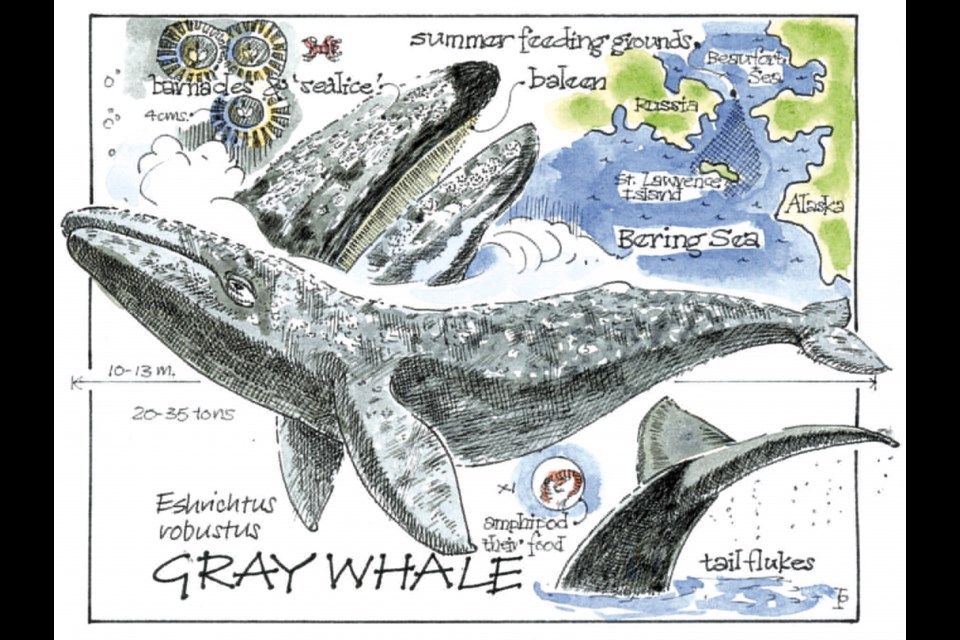

The Aleut word agunalaksh means “the shores where the sea breaks its back.” The sea that breaks its back is the Bering. It is where the poet Corey Ford said the “war between water and land is never ending.” Every spring, 26,000 grey whales travel along the West Coast to one of the harshest places on Earth. To grey whales, it has always been a banquet hall. The wars of water and land, driven by wind and current, have thrown their dead up from the bottom. The dead are delivered as carbon — the black gold of the sea, the matter on which everything relies. Carbon is the manna of phytoplankton, in turn the feast of zooplankton, which fuel the amphipods that feed the kings of the sea — the great behemoths of the Bering. There they feed on amphipods, the tiny shrimp-like animals that live in the mud, before returning to Baja to calve and breed.

In the past 30 years, the grey whale population has rebounded, returning to historic levels that would have been observed in the Bering before they were hunted into near extinction. Now every March/April, we watch thousands of them pass by as they migrate up along the outer coast of Vancouver Island, feeding right into rocky-ledge shores along the way. Lots of them stay all summer and then join the southbound migration back to Baja in October. A small group has even returned to Puget Sound in the south Salish Sea for summer foraging. They are called Sounders, plowing up the estuaries to filter out ghost shrimp.

A behemoth was thrown up from the bottom of the Salish Sea 7,000 kilometres short of agunalaksh, it died on “the shores where the sea laps the rock” under a flashing sign that said “Moby Dick’s Pub” on Salt Spring Island. The animal died of starvation and was the ninth to die in British Columbia that year. The causes of death in any whale population are always complex. Populations travelling that far with young will always suffer a few losses. Whale scientists point to various causes of declining food stocks, including population saturation, as numbers rise back to historical levels. There are constant pressures on the migrating whales, including cruise-ship collisions and the stress of whale-watching when the whales will forgo the best feeding grounds for the quietest. Other causes are the declining richness of their banquet hall.

Vitus Bering first crossed the sea that took both his name and his life 250 years ago. The brilliant German naturalist Georg Steller accompanied him. Steller, with his articulate pen and mandate from the Russian fur traders, recorded the type and numbers of the flora and fauna between the warring lands and water.

Today, the Bering Sea seems to be a shadow of what it was. There have been major declines in marine mammals, bird populations and forage fish. What contemporary scientists have found is that the history of what has happened can be tracked annually in the long baleen plates of filter-feeding whales, like tree rings.

Each summer, as the whales feed in the sea, a certain percentage of carbon 13 is laid down in a layer of baleen that reflects the amount of phytoplankton that year. At an archeological site on an island in the Bering Sea, a strip of a sled runner made out of baleen was recovered from a house site abandoned in 1871. It provided a benchmark of how much carbon 13 could be expected to provide for the richness that Bering described.

The percentage of carbon from whales that had lived during the second half of the 20th century was within the same range until 1965, when it started to decline severely. Zooplankton levels in the Bering are correspondingly low and the forage fish that rely on them have suffered too. Changing climate, currents, or the natural limits to growth are all causes. There are no simple answers, but when you watch the emaciated carcass of a dead whale lie under the undignified lights of a bar, you know that it is humans that can break or not break the sea’s back.

Calypsos and Quests

This is a story for my two boys. They are hearty men now full of earthy wit and valour, well on in their manhood quests. Every spring before puberty, they would join me on a smaller quest to find Calypso orchids hidden in the forest. This is the lecture in comparative mythology that I delivered before they ran kicking and laughing into adolescence. Poor kids, but they turned out all right.

There once was a shy nymph from the island of Ogygia. She was the goddess daughter of Atlas and went by the name of Calypso. One day, Odysseus, the son of the King of Ithaca, was shipwrecked on her island. Odysseus was a handsome, hearty hero and full of earthy wit and valour. He discovered Calypso concealed in the forest and she fell desperately in love with him. He was stranded and couldn’t leave the island, and she begged him to stay forever, promising him eternal youth. Odysseus was young and longed to get back to his quest, and eternal youth had no appeal. After seven years of holding Odysseus captive, Calypso finally relented and built him a raft, releasing him back to his quests and the prospect of old age. He left behind a lover, gazing out to the Adriatic after him.

In the forests of our islands in the Pacific, you might remember discovering Calypso. The name of the coast’s most beautiful and secretive wild orchid commemorates that Greek goddess. Although I usually put up quite an opposition to names that are derived from stories made up almost 20,000 kilometres away, I have to admit a certain fondness for Calypso (the Haida called them Black Cod Grease). She embodies an eternal human condition — unrequited love, and she behaved well in the end. She made him a raft, she put together some sandwiches and a Thermos flask, and she kissed him and waved him a fond farewell. And Odysseus embodied another eternal human condition — the need for quests — and he behaved well, too. He was true to his own nature and never lied. He also knew better than to trade his soul for eternal youth.

One day, you might want to go and visit those Calypso orchids. It is the kind of beauty you would expect to flourish on a magical island with nothing but the sun, wind, forest, and waves to cultivate. There are five dancing sepals and petals, the colour of which can only be described as sweet Calypso madder. They catch the droplets of dew and direct the mead and pollinators into the fecund lips of mottled sienna, white and raw ochre where all creation begins.

Remember this image of creation. In one sense, Calypso is a subtle and fragile beauty — not to be spoken about, as if in the mentioning of it, it will be lost, just like her tenuous hold to the Earth through a few spiderweb-like root filaments attached to her bulb (or corm) or her rare scent, which only hits you in the aftermath of an April shower soaking into the dark forest duff.

Like the goddess, the orchid’s real essence flourishes in association with an earthy character — like Odysseus. Calypso only germinates and grows when there is a particular species of mycorrhizal fungus whose own filaments penetrate the seed to convert unusable starches into usable sugars. That association is most intense in the first seven years, as the embryo plant develops to maturity. Pollen is the lover, but fungus is the friend — a nurturing but vital type of friend. If truth be known, it is better to pine for a good friend than grow immortal with an unwilling lover.

When you were little it was easy to spot Calypso, as you were so near to the ground and had an eye for small things concealed under the windfall of the winter storms. Odysseus showed his true heroic qualities by finding her as an adult and then leaving her. There are many who don’t. There will probably be a while that you don’t, too.

You’ll join the throng of audacious mortals who charge through the forests of our islands, tripping on the delicate filaments attached to the earth while wired to pounding tunes, throbbing wheels or pulsing chainsaws. You’ll try out manufactured scents that drown out the ephemeral perfume riding on the air. And the unmentionable subtle colours of Calypso-madder lips spotted with dew will be outshone by the fluorescent glow of your Nike Icons.

But halfway through the quest, I hope your memories of something richer will kick in, and you will notice this rare plant once again. And I hope that you will do the heroic thing and leave her, since once picked, the orchid dies forever.