The inquiry was set to begin on Friday, Dec. 15, 1905. That day started early for Cameron. It was cloudy but mild, and butterflies were flitting about the garden. She thought it an unusual sight, so near to Christmas. The shops in town were gearing up for another holiday season, but twinkling lights, Swiss chocolates, sweet meats and fat turkeys were far from her mind. She was in a very sombre mood. This was her last day as a teacher and principal at South Park School. A group of the boys from her school wished to show their support for their principal and took a British Blue Ensign, which they had previously won in a drill-team competition, reversed the Jack and raised the flag at half-mast. It stayed that way for the remainder of the day.

When Cameron walked through the dramatic arched entrance of Bastion Square and into the notable, castle-like courthouse, the ghosts were not active, or if they were no one took any notice. Facing her was an exquisite, ornate gilded birdcage-style elevator that would take her up to the third floor where her case was being heard. The intricately entwined grillwork was not unlike her case, which was similarly entangled. It was a strange coincidence that her fate would be decided in a building that had been designed by the same architect who built South Park School. When Cameron walked into the courtroom, the dark panelled walls smelled faintly of beeswax. The wide planked floors rested heavily with the weighty issues that trod upon its timbers.

The courtroom was packed with teachers, school administrators, newspaper reporters and a substantial assemblage of students from South Park School. Cameron sat quietly with an air of composed determination. Everything she had worked for, her professionalism, her integrity and the person she had become, hung in the balance. She would have her say and hoped to be finally vindicated.

On Friday, Feb. 23, 1906, His Honour Judge Lampman handed his findings in the drawing-book case to the provincial secretary, F.J. Fulton. Cameron’s lawyer had always been forthright about her chances of success, but she was not prepared for Lampman’s summation. His report was well thought out, and exhaustively detailed all aspects of the case in a 33-page document. He found that there was a great deal of ruling and that the examiners’ decision to toss out the students’ workbooks was completely justified. He chastised Cameron for failing to ensure the students’ work was done fairly and according to the rules and regulations: “If Miss Cameron, when she certified to the books, did not know of the ruling she should have known it. … I think she was careless.”

The ruling was a crushing blow for her, although she must have suspected at various points throughout the hearings that the case was not going in her favour. It was also a difficult decision for her supporters to hear. Cameron felt that she had let everyone down.

It is impossible to dissect the rationale for her actions; that lay deep within her psyche. On the surface, she said she believed that she had to protect the integrity of her students. It is possible that she may also have been weary of the constant haranguing she received from the school trustees and hoped to teach them a lesson. She brought professionalism to the job of teaching and was possibly impatient with those who were not as conversant as she was in educational methodology.

She was not inflexible and unbendable as her opponents claimed. She was present at the beginning of the development of the public school system in British Columbia, which was still struggling to find its way. In every sense, she helped to shape that system. At times, she was at loggerheads over the purpose of education. She was uncomfortable with the direction away from a classical and liberal arts curriculum toward a more practical, job-oriented approach.

Although she was aware of the important interplay between education and the economy, apprenticing for occupations, she often said, was best learned on the job, but should be augmented by a classical education. She believed that logic, debate, writing and mathematics were critical to any job and should not be crowded out by vocational courses.

The trustees, too, were caught in the shifting sands of power. As duly elected officials they were responsible to their voting public who were concerned about the rising cost of education and the continual controversies besetting education. As the arbiters for curriculum, they often came head-to-head with teachers when they unilaterally tried to affect the actual process of learning — a realm that teachers felt was best decided by themselves and their professional teacher associations. The teachers found decisions about the course of education were often politically motivated and frequently based on conjecture and supposition about the state of the economy and the current direction of society.

One of the problems with the drawing-book exercises, which were at the root of the case, was the amount of subjectivity, both in the design of the questions and in the marking. Lack of objectivity necessarily leads to bias and prejudice. It was impossible to test the strengths and weaknesses of [the examiner] David Blair’s system, as he had not developed any criteria to analyze the reliability and the validity of his drawing program. It is likely that Blair’s system would fail both measures today. Many of the teachers decried the lack of such measures for assessing their students’ work.

In 1905, teacher training had not been significantly addressed, nor had learning goals been clearly established. There was no way to ensure the existing teaching methods were appropriate. In the absence of such self-examination, Lampman’s only option was to find fault with the actions of Cameron. This was a tiff that had spiralled out of the control of all the parties in question; a Royal Commission should never have happened.

Lampman’s decision pained her deeply because it questioned not only her integrity but also her professionalism. The trial had lasted for 16 weeks. She was exhausted in body and soul and was deeply in debt over the cost of the case and the fight to retain her house. Try as she might she could not summon up her mother’s adage of never letting sorrows or hardship take the joy out of life. Some years later she wrote: “When I think how I suffered those days in that iniquitous Royal Commission watching the door for a messenger from home where the dear Mother was slipping away from me hour by hour, I have murder in my heart.”

The teachers in the province took note of the decision. The 36th Annual Report of the Public Schools of British Columbia, 1906-1907 stated that the biggest improvement in individual subjects that year was in drawing and art. Many of the schools increased their time spent teaching freehand drawing from objects and incorporated art with the other subjects of the curriculum. Blair had won the day, but he was a deeply unpopular man, and his drawing program was not well liked by the teachers.

Book excerpt

Book excerpt

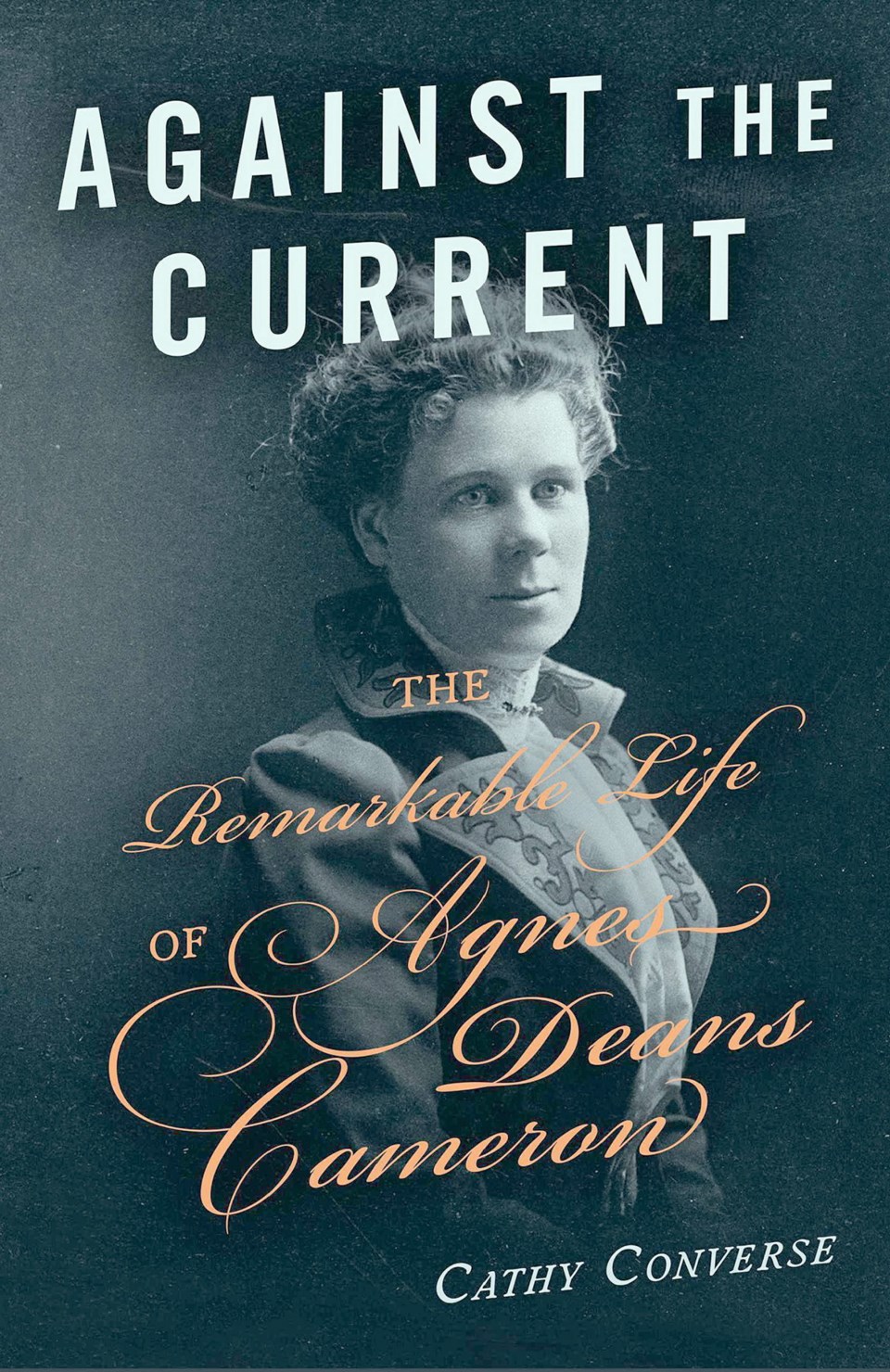

Against the Current: The Remarkable Life of Agnes Deans Cameron

TouchWood Editions ©2018 Cathy Converse

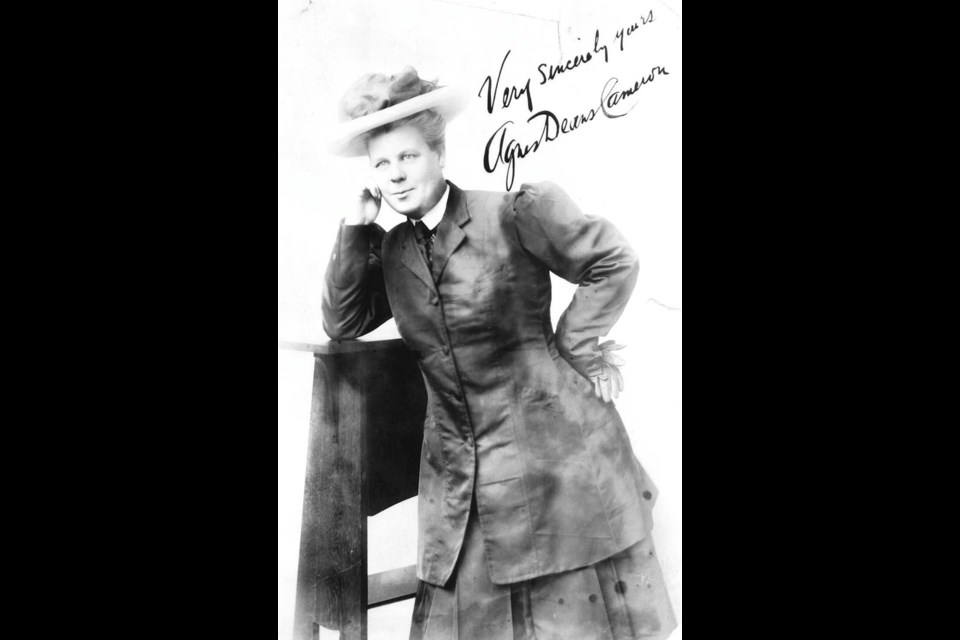

Agnes Deans Cameron (1863-1912) was an author, journalist, sportswoman, orator, adventurer, international celebrity and British Columbia’s first female principal, a post she filled at Victoria’s South Park School. Despite an illustrious career, she was periodically at odds with the arbitrators of education and, for many years, the school trustees sought a way to dismiss her. Their opportunity came at the end of term in 1905 when she was accused of allowing her students to use forbidden rulers to draw lines and triangles in their final examination booklets for drawing and art. The result was a long, drawn-out battle that led to a Royal Commission. In Against the Current, a new biography of Cameron, local author Cathy Converse recounts the events of her life, her power struggles with the school trustees, and the adventures she embarked on following her suspension from her career in education.