With Nelson Mandela on life-support in a South Africa hospital eight days before his 95th birthday, his “death watch” attracting international media coverage, a flood of tributes and TV specials about the country’s first black president seems inevitable.

Jason Bourque, a Vancouver-based filmmaker who launched his career writing and directing shorts, commercials and music videos in Victoria, is also finally attracting attention for his passion project about the anti-apartheid revolutionary.

Music for Mandela, which he started shooting in June 2011, is unlike any other portrait of the global icon and Nobel Peace Prize winner, who was jailed for 27 years before being elected president in 1994, says Bourque, 40.

The documentary he developed with producer Ken Frith, his partner in Gold Star Productions, explores the role music plays in Mandela’s life and how the freedom fighter used it as a weapon against apartheid and to inspire hope and change worldwide.

“It’s surreal, because at that point, there wasn’t a lot of interest in Mandela,” said Bourque, recalling the film’s genesis. “Our goal was to make a tribute to the world’s greatest living icon and now we’re seeing a groundswell based on his health.”

Bourque and Frith were inspired to make the documentary by watching Peter Gabriel, Simple Minds, Sting and other favourite musicians perform during the Free Nelson Mandela 70th-birthday tribute broadcast from London’s Wembley Stadium in 1988. It would become a celebration of Mandela’s “legacy with a backbeat,” its subtitle.

“For me, finding out about Nelson Mandela was through music,” said Bourque. “Music let me incorporate more of my passion and allowed for a more creative angle, on how he used it politically and personally and how his perseverance, simple messages of hope and especially forgiveness could inspire musicians.”

When Bourque wasn’t working on his bread-and-butter projects — from Darwin’s Brave New World, which he co-directed, to Stonados, his SyFy Channel disaster flick filmed here about the deadly impact of stone-filled tornados in Boston — he quietly developed his Mandela project, being distributed in Canada by Kinosmith, with Frith and executive producer Toby Dormer of Remedy Productions.

Their mutual love of music and Mandela’s story prompted Bourque and Frith to make a successful documentary pitch for funding through the Harold Greenberg Fund. Doors started closing, however, after initial attempts to reach out to U2, Beyoncé and other cultural ambassadors, with all roads dead-ending at the Mandela Foundation.

With no broadcaster involved, it took them a while to figure out how to proceed.

“It’s when we hit the ground running in Africa that doors really started to open,” said Bourque, who opted for a more personal approach as the documentary, fuelled by co-operation from exiled musicians and South African crews, took on a life of its own.

While the film contains stock footage to address the historical background of one of the world’s most documented figures, Bourque chose to focus more on musicians and inspirational visuals.

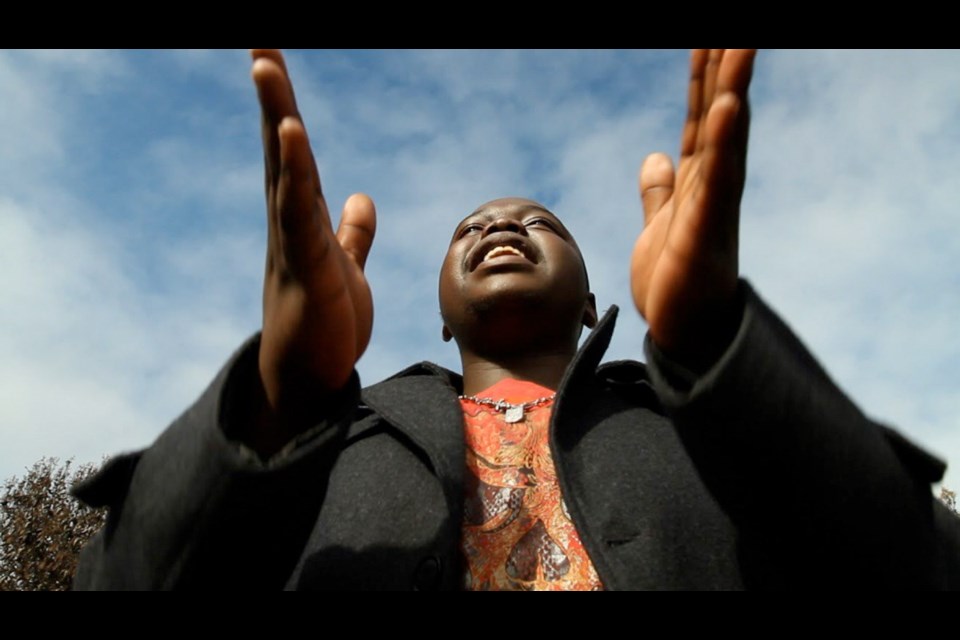

“We focused more on the grassroots of how he inspired musicians in the townships,” said Bourque, whose subjects include Ladysmith Black Mambazo; Mandela’s grandson, hip-hop artist Bambatha Mandela; B.B. King; Eddie Daniels; Welsh opera star Katherine Jenkins; Emmanuel Jal; Vusi Mahlasela; and the Soweto Gospel Choir.

“Instead of going to L.A., we went to Johannesburg and Cape Town,” Bourque said.

Highlights included when Mandela’s right-hand man, politician Ahmed Kathrada, gave Bourque a tour of the infamous Robben Island prison where Mandela spent 18 years, and the lime quarry where he worked.

First-hand accounts by Mandela’s longtime friend and former inmate Eddie Daniels were particularly revealing, he said.

“He described Mandela giving concerts in jail cells to prisoners to lift their spirits,” said Bourque, whose film also acknowledges the “cultural war” — how Mandela print material and images were banned, and tracks inspired by Mandela were scratched off records.

Kathrada eloquently expanded on a topic the political prisoners rarely talk about, Bourque said.

“Hearing about these songs they’d sing at the lime quarry was fascinating,” he said. “They were singing workers’ folk songs, and at the same time, Mandela compared the apartheid struggle to the motion of an oncoming train. It was very subversive.”

Other highlights include guerrilla-style footage of street dancing in Mandela Square and the interview with B.B. King they did when the blues legend was in Vancouver.

“He was incredibly funny and charming and touched,” Bourque recalled. “He said he wished the world had more Mandelas.”

No stranger to documentaries, Bourque is best known for Shadow Company, his exposé of the private military industry.

“It’s easier to knock a documentary out of the park than a SyFy Channel movie,” he jokes, referring to Stonados. Its April 27 broadcast date was twice delayed (until November) because of sensitivity over Hurricane Sandy and the Boston bombings.

“You cannot pick on Boston right now, even with ‘stonados,’ ” he said.