A perplexing murder in Victoria’s Chinatown in 1904 is revisited in this excerpt from Susan McNicoll’s dramatic true-crime collection spanning a century of foul play in British Columbia.

The chicken oath notwithstanding, Wong Gow and Wong On were not believed in 1904 when they declared their innocence in the murder of Chinese theatre manager Man Quong. He had been brutally beaten and then thrown over the balcony onto the stage of his own theatre. It seemed like an open-and-shut case when two men were arrested for murder after being identified by witnesses as the killers. In the theatre, though, everything is an illusion — and as in most good murder mysteries, this one had a twist.

British Columbia’s Chinese community was thriving, but it had a dark side. The population of Victoria’s Chinatown in 1904 was growing quickly, and Chinese immigrants gravitated to a six-block radius in the downtown core. Most of them joined “tongs,” essentially Chinese guilds, associations or secret societies.

Tongs were very important to Chinese immigrants because they recreated familiar institutions from home, giving the immigrants a sense of social security in a new land where they were often excluded. Tongs protected their members from outsiders, and fights between warring tongs in China even occasionally found their way to Chinese communities overseas. Tongs would also play a major role in the murder of Man Quong.

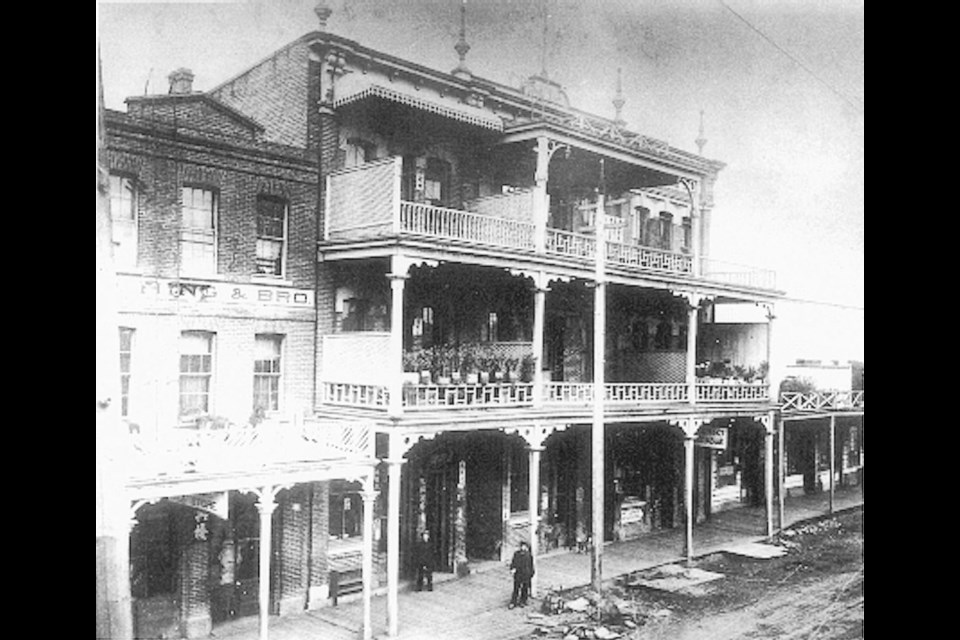

Quong was an actor and manager of the Chinese Theatre, which was located in Theatre Alley off Cormorant Street in Victoria. Both Theatre Alley and the more famous Fan Tan Alley formed the core of Chinese nightlife in the city at the turn of the 20th century. Fan Tan Alley, in fact, had the first gambling houses in British Columbia.

Only 60 metres long and too narrow to allow two people to walk through side by side, the alley still held numerous gambling houses and many restaurants to feed the gamblers. Most immigrants were male (often leaving wives and children in China), had low-paying jobs and lived in rundown rooming houses. They drank and gambled to relieve loneliness.

Prostitution was rampant, and opium houses did a steady business. In fact, opium addiction was becoming a problem in Victoria at that time, although the opium houses were completely legal and the British Columbia government made a great deal of money by imposing annual licensing fees on the operations.

Off Cormorant Street, Theatre Alley was also thriving in those days. Slightly wider than Fan Tan Alley, it held the Chinese Theatre, which was entered from a wooden staircase in the alley. It was a big room filled with long wooden benches and lit by only a few bare-bulb drop lights. Heat was provided by two wood stoves, and on each side of the stage was a stairway leading to the balcony, whose front consisted of a low, white picket fence. Off the balcony, a door led to dressing rooms, including one where Quong lived.

The plays produced were very stylized and similar to today’s soap operas. They had innumerable acts that continued for weeks. You could see Act 1 on Monday and then pick up the story in a later act on Friday. In Chinese tradition, all the cast was male, with female roles being played by men dressed as women. The villain always wore white makeup to be easily recognizable. The orchestra played at intervals throughout the performance and usually consisted of a one-string fiddle, a three-string banjo, drums and gongs. Scenery was almost non-existent, mainly chairs and wooden planks.

After the performance each night, Quong would make his way to the clubs in Fan Tan Alley where he enjoyed all they had to offer. In early 1904, however, all was not well in Theatre Alley. Quong had been threatened repeatedly for a couple of weeks, although by whom he did not say. Fearing for his safety, he had refused to go out except in broad daylight and in the company of his friends.

Since the threats began, Quong had been unable to do the rounds, and he missed all the nightly entertainment. So, on Jan. 31, 1904, Quong decided to bring his friends to the theatre for some revelry instead. He would feel safe there and would have control over who entered.

By midnight, the play was over, and the actors had left. Shortly after that, Quong’s guests arrived. It was close to 12:30 a.m. He vigorously inspected the arrivals for any concealed weapons. He was very tense, but food, Chinese wine and opium soon lightened the mood considerably for him and the others.

About an hour later, according to eyewitnesses, there was a loud knock on the door leading out into Theatre Alley. Quong thought it might be a late guest and opened the door a crack. It was flung back forcefully and two men stood in front of him, with others behind.

The intruders rushed at Quong. They grabbed him by his queue (the traditional plaited pigtail the Chinese then wore) to stop his escape and then beat him with iron bars. Carrying his battered body through the door onto the theatre’s balcony, they flung it over the edge, more than four metres to the stage below. Quong’s body struck a table onstage before landing on the ground.

The assailants quickly disappeared. Some of the guests rushed into Theatre Alley and gave chase, while others headed to the police station to report the attack. Const. George Carson was the first policeman on the scene. He found Quong still lying on the stage, in obvious pain but conscious. After helping Quong into a chair, Carson went off to summon Dr. Robinson.

When the two returned, they found Quong had been taken to his bed by friends. The doctor quickly realized that Quong was seriously injured and sent him to Jubilee Hospital. He died there about 6 a.m. Some of his friends reported that when Quong realized he was dying, he told them he knew who some of his assailants were and begged that they be arrested. He had given their names to his friends.

Three iron bars reportedly used to beat Quong were found in a small passageway near his room. Later in the morning, Det. George Perdue was added to the investigation. Quong’s friends told Perdue that one of the dead man’s assailants had been Wong Yuen, a musician at the theatre who had recently seen his salary reduced by the Chinese state. He and Quong had had a previous fight, but things were smoothed out and Yuen was allowed to stay in the orchestra. Nevertheless, witnesses told the court that Quong and Wong Yuen had quarrelled again the night before the assault.

The musician was not to be found after the murder, but two of his cohorts were — Wong On and Wong Gow. They were quickly identified by the witnesses as two of those who had attacked Quong, and they were arrested.

The Wongs were infamous in British Columbia, as evidenced by this report in the Vancouver Daily Province from Feb. 3, 1904: “[One of the Wongs] in this city has gone to Victoria ostensibly for the purpose of directing the defence of men since arrested …Wong Sai Yow, popularly known in the Chinese colony of Vancouver as the Gold Tooth Fellow, went to Victoria on Monday. He bears the reputation of being the leader of the Wong family, which is a very bad lot, and just as many as possible of its members are now being gathered in by the Victoria police. Wong Sai is said to be an ex-convict from the State of Oregon and is said to have been high in the councils of the Highbinders.”

On Feb. 8, 1904, the jury at the inquest ruled “murder by person or persons unknown,” although that wasn’t quite accurate. They did know, because three days later the preliminary hearing of Wong On and Wong Gow for the murder of Man Quong began.

The first full day of the hearing began uneventfully with a drawing of the theatre being shown and Constable Carson testifying about where he found Quong’s body. Haw Fat Chung, an actor in the Chinese Theatre who had been present at Quong’s party, was then called to the stand. This precipitated a major problem over the nature of the oath he would be required to make before his testimony.

The oath used in 1904 was a Christian oath, but the Canada Evidence Act allowed substitute oaths for non-Christian witnesses. When Chinese witnesses testified, three oaths could be used:

The Paper Oath — The witness wrote his (or her) name on a piece of paper and, while burning the paper, took an oath that if he did not tell the truth his soul would be consumed by fire just as the paper was.

The Saucer Oath — On the stand, the witness knelt down, the clerk handed him (or her) a china saucer and the witness broke it against the box. The witness then took an oath that his soul would be cracked like the saucer if he did not tell the truth.

The Chicken Oath — A chicken was obtained. The witness was handed a piece of paper that said words to the effect, “Being a true witness, I shall enjoy happiness and my sons and grandsons will prosper forever. If I give false evidence, I shall die on the street, I shall forever suffer in adversity, and all my offspring will be exterminated. In burning this oath, I humbly submit myself to the will of heaven which has brilliant eyes to see.”

The witness, court and jury would then retire to a convenient place outside the building where the oath could be administered. In addition to the poor chicken, a block of wood, an axe or knife, no fewer than three punk sticks (small pieces of rotting wood usually used as kindling), a pair of candles and Joss paper (traditionally made from coarse bamboo paper and decorated with seals, stamps or motifs) were also needed.

The candles were stuck in the ground and lit. The oath was read aloud by the witness, who then wrapped it in the Joss paper. The witness would then place the chicken on the block of wood and chop its head off, set fire to the oath with the candles and hold the burning paper until it was consumed.

Witnesses in court were usually asked to pick the oath they thought would be most binding on them to tell the truth. With Haw Fat Chung now preparing to take the stand in the Wong trial, the issue of the oath took centre stage. W.J. Taylor, who represented the accused, quoted an authority in which it was asserted the chicken oath was the most binding. The choice was up to the person testifying, and Haw Fat Chung chose the chicken oath.

The proceedings quickly came to a halt again because the translation of the oath was so poor that the court interpreter refused to administer it because of “conscientious scruples.” An adjournment was ordered until 2 p.m. so that a new form of the oath could be translated into Chinese.

This time, Haw Fat Chung was satisfied and signed the oath. It seemed as though the hearing was at last moving forward-until an argument broke out between the prosecution and the defence over who was responsible for paying for the chicken, punk sticks and everything else needed for the oath.

The prosecution claimed it was up to the defence to provide the chicken. Taylor refused to do so, as did George Powell, appearing for the prosecution. The judge announced that the case could not go on, but something had to be done to give the prisoners a preliminary hearing. Finally, the prosecution relented and said they would supply the chicken, but they needed time to do so.

The judge, wanting to move forward, suggested to the witness that he consider choosing one of the other two oaths. Haw Fat Chung said neither of those would be as binding on him as the chicken oath. An adjournment was called until the next day.

Finally, Haw Fat Chung took the stand. He testified that he knew both the accused men and Quong and that there had been a fight between Quong and Wong Yuen the night before the murder. At the end of the fight, he said, he had told the crowd to disperse and testified that Wong On told him: “Oh, you’re taking Man Quong’s part. We’ll bring you out and cut you to pieces … Look out for tomorrow. You’ll die then.” Along with a number of others, Haw Fat Chung then fingered Won On and Wong Gow as two of those who attacked Quong with the iron bars before throwing him down onto the stage.

This was enough for the judge, who bound the two prisoners over for trial, to begin May 4, 1904.

Among those who testified for the defence was Dr. Davie, who stated that no one could be beaten with iron bars without marks showing up on the body. There were none. There were also witnesses for Wong On who proved he was elsewhere that night. On the other hand, eight other witnesses all swore that he and Wong Gow were among the killers. On May 9, the jury found the two Wongs guilty of murder and Justice Irving sentenced them to be hanged July 22, 1904. Four accomplices were still at large, and the Chinese Benevolent Society issued a proclamation against the Wong clan and offered a reward of $150 for each of the missing four.

British Columbia Murders: Notorious Cases and Unsolved Mysteries © 2010 Susan McNicoll. Heritage House, heritagehouse.ca