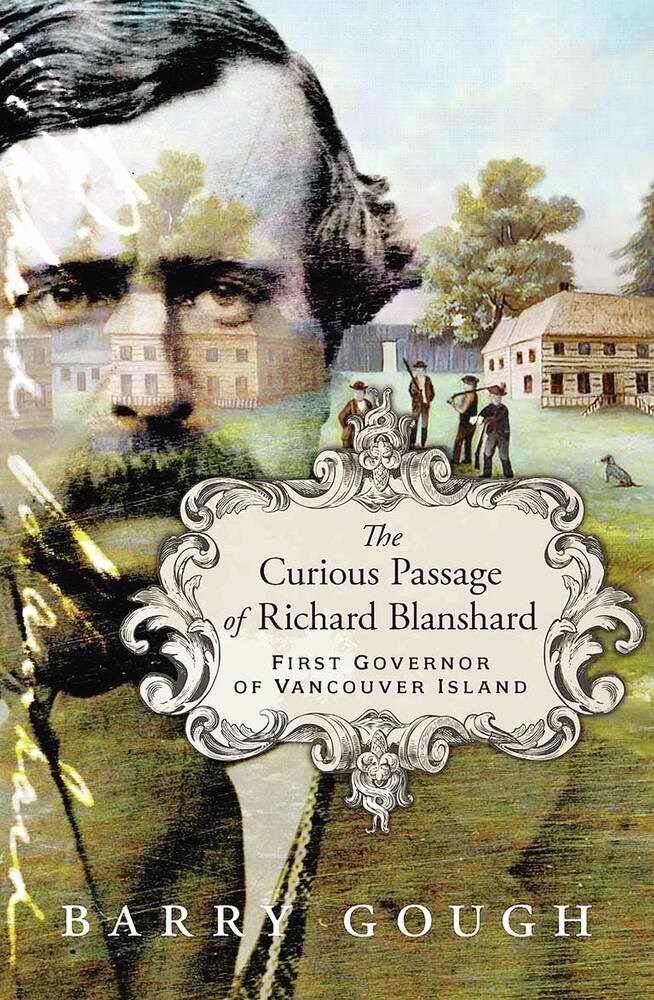

The Curious Passage of Richard Blanshard: First Governor of Vancouver Island

By Barry Gough

Harbour, 329 pages, $38.95.

Reviewed by Dave Obee

Richard Blanshard has a notable place in the history of British Columbia. He was the first colonial governor of Vancouver Island, which meant he was also the first governor the British government appointed west of Ontario.

One of the most important streets in Victoria and Saanich bears his name, as does a provincial government building at the intersection of Blanshard and Pandora Avenue.

Blanshard’s role is, however, easy to forget, because he was here for only 18 months, from March 1850 to September 1851, and he failed to accomplish most of what he set out to do. Besides, everyone knew that James Douglas, the chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, was really in charge.

At that time, Vancouver Island was still under the firm hand of the company, and Douglas was not about to relinquish his control to the newcomer.

Several books have been written about the role of Douglas in developing Vancouver Island and, later, all of British Columbia, but this is the first major look at the life of Blanshard. It’s about time.

Barry Gough, the preeminent historian on the early years of this area, has written a biography that casts Blanshard in a new light. It is a sympathetic view that allows the reader to gain a better appreciation for the challenges that Blanshard faced.

For one thing, he was repeatedly stymied by Douglas. While Blanshard’s list of accomplishments is not long, he was up against the largest corporate monopoly ever seen in western Canada.

Blanshard was not paid for his service. He was not even fully reimbursed for the cost of his travel to and from Vancouver Island. The thinking had been that as settlers arrived and resources were extracted, there would be money to pay for the operation of a government, including a salary for its governor. He soon realized that he would have to wait a long, long time.

He found that the cost of living was high, because everything had to come from the Hudson’s Bay Company. Blanshard paid the top rate for what he needed, while his nemesis Douglas got a staff discount.

Before leaving England, Blanshard was promised 1,000 acres in the new colony. He dreamed of establishing an estate suitable for himself and Emily Hyde, the love of his life, who was waiting for him in England. He was not given the land.

He thought he would arrive to a house in keeping with the importance of his role. Nothing was ready for him, and Douglas did little to encourage speedy construction of the governor’s cottage.

Beyond all of that, Blanshard was ill, suffering from a virulent form of malaria. That would have been made worse by the lack of medical help here, and the need to live in rough conditions such as an unheated storage shed.

Despite all of the obstacles facing him, Blanshard established the government on Vancouver Island. That government of the runt of a colony led to the province of British Columbia that we know today.

Blanshard’s task was much harder than other historians might have considered, and it was certainly harder than it was for the man who succeeded him as governor, James Douglas. Blanshard deserves praise for his role, not the belittling that has become common.

But wait, there is more — because Gough does not restrict his work to Blanshard’s life and times. He goes well beyond the first governor by setting the scene with comprehensive background information that covers many years before and after Blanshard’s term.

That additional material includes a thorough look at the issues that arose from the settling of the international boundary, and reminds us of the concern felt on the Island when it seemed that the United States was going to try to gain control.

All in all, this is an enlightening book, one that meets the high standard that we have come to expect from Barry Gough.

Given the common perception of Blanshard and a shortage of source documents, it would not have been easy to tackle this project — but Gough’s willingness to take it on is fitting. After all, it wasn’t easy for Richard Blanshard, either.

The reviewer is the editor and publisher of the Times Colonist.