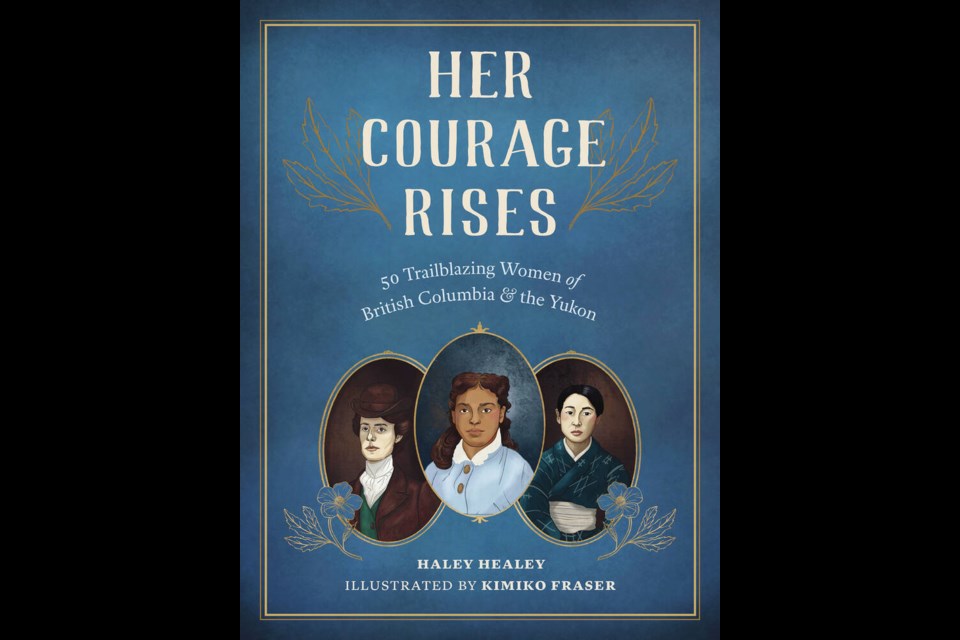

Excerpt from Her Courage Rises: 50 Trailblazing Women of British Columbia and the Yukon by Haley Healey, illustrated by Kimiko Fraser (Heritage House, 2022), reprinted with permission of publisher.

A B.C. bestseller, Her Courage Rises is a beautifully illustrated collection of inspiring life stories of 50 extraordinary historical women from B.C. and the Yukon.

In honour of International Women’s Day today, read about three exceptional women from Victoria: Isabella Mainville Ross, a Métis woman and the first female landowner in B.C.; Hannah Maynard, the first official photographer for the Victoria Police Department; and B.C.’s first professionally educated librarian, Alma Russell.

Isabella Mainville Ross: Landowner; 1808-1885

Many on Vancouver Island know of Ross Bay Cemetery, but fewer know of the woman who once farmed the land where the cemetery sits. This woman was Isabella Mainville Ross, and she was the first female registered landowner in what is now British Columbia.

Isabella was born on January 10, 1808, likely near modern-day Fort Frances, Ontario. Her mother was Ojibway and her father was French and Spanish. In 1822, Isabella married Charles George Ross, a boatman for the Hudson’s Bay Company. The couple moved from Fort Frances to Fort Vancouver and then to Fort McLoughlin — a fur trade outpost on Campbell Island near modern-day Bella Bella. There, when Isabella was trading on behalf of her husband, who was away, a man pulled a knife on her son. Isabella grabbed a knife of her own, charged at the man, and chased him out of the fort.

The family’s final move was to Fort Victoria, in 1843. Charles was promoted to Chief Trader for the HBC, and was in charge of supervising the construction of Fort Victoria. He died suddenly, leaving Isabella widowed at 36 years old, with nine children, including a newborn, a toddler, and three children under 10. They moved to Fort Nisqually near Puget Sound, Washington, where they lived for eight years.

The family eventually moved back to Victoria and, with money left to her in Charles’s will, Isabella purchased 99 acres of land. This acquisition was significant and historic for several reasons. It made her the first female landowner, and likely the first Indigenous person, to own land under colonial law in what is now British Columbia.

Isabella named her property Fowl Bay Farm, after the area’s waterfowl.

Isabella’s children attended school while she worked the land. Isabella sold livestock and farm produce. Though she couldn’t read or write English, she spoke French, Ojibway, and likely Chinook Jargon, a language used for trade. All her children lived to be adults — an unusual occurrence in days of high infant mortality rates and rampant disease.

A tall, handsome headstone in Ross Bay Cemetery bears Isabella’s name, on the very land where she used to grow potatoes and raise livestock. She was the first woman to own land on Vancouver Island and a prominent Victoria woman whose name will remain in the city where she lived her pioneer life.

Hannah Maynard: Police photographer; 1834-1918

It’s 1898 and you enter a building off Johnson Street in Victoria. You walk through a shoe shop, up a staircase, and pull back a black velvet curtain. Welcome to Hannah Maynard’s Photographic Gallery.

Hannah was born in Cornwall, U.K., in 1834 and married her childhood sweetheart. They moved to Canada, first living in Bowmanville, Ontario, then in Victoria. Victoria was booming and Hannah wasted no time in opening her studio on Johnson Street. Photography was in high demand and Hannah had taught it to herself while in Bowmanville.

Innovation is evident in all of Hannah’s work. Throughout her career, she experimented with cutting-edge photographic techniques, like image manipulation, mirrors, masking, and multiple exposure. Hannah loved self-portraits and composites that showed the same subject multiple times. One photo plays with trick photography and pokes fun at the ritual of teatime. It shows three Hannahs: one sitting at a table pouring tea and another looking at the camera from a picture on the wall, pouring milk on the head of a third Hannah.

Photography was an unusual profession for a woman in Hannah’s day. Some people boycotted her gallery, not wanting to support a female business owner. But Hannah persevered, eventually teaching her trade to her husband Richard and even hiring an assistant.

In 1887, Hannah’s career took an exciting turn. She became the first official photographer for the Victoria Police Department. Criminals of all sorts came to her studio for mug shots. Hannah cleverly used a mirror to get a full face and profile in the same shot. Hannah retired in 1912, not because she was tired, but because she wanted to give the next generation a chance. She died in 1918 and was buried in her family plot in Victoria’s Ross Bay Cemetery.

Hannah Maynard was a stunning original — the late 1800s version of what we might call an “early adopter” of technology. It was remarkable enough to be a female entrepreneur in her time, but even more so to innovate the way she did. She constantly experimented with techniques decades ahead of her time. And yet, despite the complexity and unprecedented nature of her work, it has gone largely unrecognized. Hannah, a talented, creative photographer who made whimsical, haunting photos that are eye-catching to this day, is a surprisingly unknown figure today.

Alma Russell: Librarian, archivist, and preserver of history; 1873-1964

After completing high school in the late 1800s, Alma Russell left her hometown of Victoria for New York City. Born in the Maritimes and raised in Victoria, she sought higher education in New York.

She studied at the Pratt Institute of Library Sciences in Brooklyn and upon graduating, was offered a job in New York City. She turned it down and returned to Victoria. Within the year, she was offered a job as librarian and archivist at the Legislative Library. It was 1897, and Alma Russell had become British Columbia’s first professionally educated librarian —woman or man.

Alma got straight to work cataloguing and classifying thousands of books in the library. Although community members could access the library, Members of Legislative Assembly (MLAs) were the most frequent patrons. Despite her expertise and recent education, Alma wasn’t paid adequately and didn’t obtain full-time work. But she persevered. She created a system for archives to be searched using catalogue cards. Her library was the first in B.C. to use the Dewey decimal system—a library classification system that shelves books with others of the same subject.

Preserving history was part of Alma’s job and one she took seriously. She lovingly looked after the Pacific Northwest History collection and created a wartime memorial project of her own. The project was an extensive collection of letters and photos from B.C. soldiers of the First World War.

Alma often spoke and wrote about British Columbia’s history. She was the first woman to be president of the B.C. Historical Association. She also served as vice president and then president of the B.C. Library Association.

In New York, Alma had learned about the Travelling Libraries program. She started one on Vancouver Island, successfully delivering reading materials into the hands of farmers, miners, and people living in Vancouver Island’s far-off nooks and crannies. This was in a time before public libraries existed.

Throughout her career, Alma wasn’t given the credit she deserved. It was only when she came out of retirement in 1934 that she was granted the title of provincial librarian and archivist. She hadn’t been given it before, because she was a woman. Today, two islands off Ucluelet bear Alma Russell’s name.

Haley Healey is a high school counsellor and registered clinical counsellor and the bestselling author of three books on trailblazing women in B.C.

Kimiko Fraser is an illustrator and historian-in-training who holds a bachelor of arts from the University of Victoria.