If a study by the Capital Regional District is correct, significant portions of the Saanich Peninsula and several Gulf Islands could suffer devastating sea inundations by the year 2050.

The study presented to the environmental services committee envisages a rise in ocean levels of half a metre over the next 35 years. It also assumes this rise is accompanied by the highest tide of the year (using a 19-year average) and by a 1.3-metre storm surge.

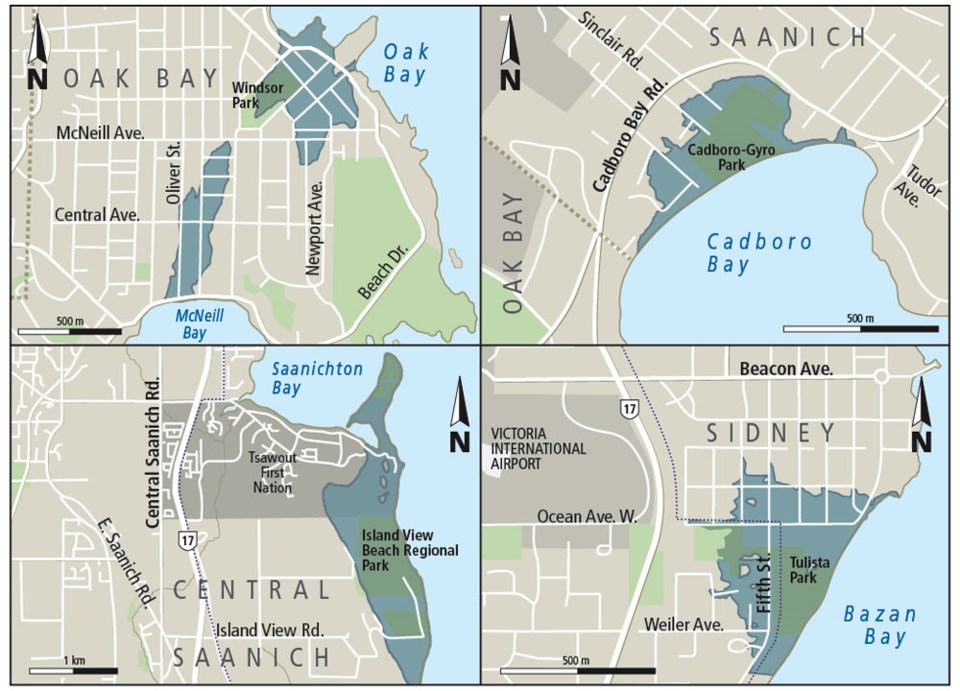

In such an eventuality, about 25 hectares of Oak Bay stretching inland behind the marina, most of Port Renfrew, about a third of Cadboro Bay’s beachfront and a good part of south Sidney would be temporarily flooded.

As well, some installations of Victoria’s Inner Harbour are vulnerable, as are Esquimalt Harbour and Tsehum Harbour in Sidney. Sections of Highway 14 between Sooke and Jordan River, the upper reaches of the Gorge waterway and Dallas Road would also be inundated.

The study was prepared by a consulting company, AECOM, to assist the CRD in future zoning and land-use planning.

Clearly, these are disaster-scale projections, not on a par with the destruction of New Orleans by hurricane Katrina perhaps, yet bad enough. But what are we to make of them?

By most estimates, ocean levels have risen over the past century by about 20 centimetres. A 50-cm lift in just 35 years would require a dramatic acceleration of that trend.

Nevertheless, these are the planning parameters issued by the provincial Environment Ministry. Shoreline geography might affect flooding severity in specific locations. But a 50-cm baseline, in the ministry’s view, is a reasonable framework to work with.

What then should be done?

On one hand, it would be irresponsible for local governments to sit idle.

If the ministry is correct, we’re talking about thousands of homes and businesses at risk, port installations and transportation infrastructure potentially destroyed. There could be legal liability for any municipality that failed to guard against such havoc.

On the other hand, what steps would be required to prevent such inundations? Dikes might have to be built around much of the Saanich Peninsula, and parts of the Gulf Islands, as well. Is that feasible?

Alternatively, local governments could designate flood zones, so that anyone purchasing property in such an area would be warned of the potential risk. That might relieve a municipality of legal liability should damage occur in the future. But what would it do to property values?

It’s difficult to know how to think about this. Earthquake planning encounters some of the same difficulties.

We can predict, with a fair degree of confidence, that a major seismic event will in fact occur. But we do not know when.

The same uncertainty exists here. A sea-level rise of half a metre during the next century is one thing. In such a scenario, there is no immediate urgency.

But if it happens in just over three decades, we are already backed into a corner. Work would have to begin in short order to get ready in time.

Perhaps the most critical question is whether the CRD believes these projections. They were published in an obscure corner of its website. There has been no concerted effort to garner attention, no serious attempt to get local municipalities moving.

Why not? Isn’t the protection of life and public safety the first duty of government?

Both the ministry and the CRD owe us an explanation. Is the threat imminent, or is it not? For if it is, we need action, not navel-gazing, and we need that action to start now.