In 2014, the Supreme Court of Canada legally recognized 1,750 square kilometres of Crown land southwest of Williams Lake as Tsilhqot’in First Nation Aboriginal title land. It represented about two per cent of traditional Tsilhqot’in territory.

Ten years later, on April 22, British Columbia’s NDP government introduced a bill to recognize Haida Nation Aboriginal title over 100 per cent of Haida-claimed territory, which represents all of Haida Gwaii’s approximate 10,000 square kilometres.

“For years, we’ve envisioned and worked towards re-establishing an economy that aligns with our values and traditions,” said Haida Nation President Gaagwiis Jason Alsop when the agreement was announced. “We can now take hold of that vision and create a future where the land and sea will nurture us for generations to come.”

Bill 25, the Haida Recognition Amendment Act—otherwise known as the Rising Tides Haida Title Lands Agreement—has been met with questions about what Aboriginal title will mean for Crown resources, parks and private properties on Haida Gwaii.

The agreement states fee simple interests will be “honoured” and will continue under provincial jurisdiction. But Aboriginal law experts are divided on the question of how private fee simple lands can co-exist in a region where Aboriginal title exists.

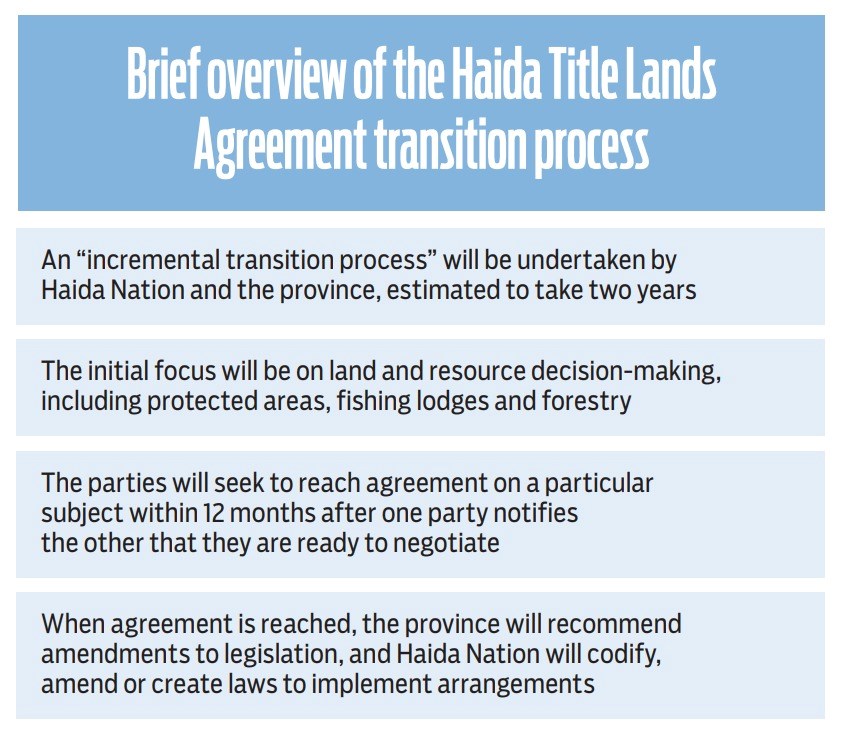

There are also questions with respect to jurisdiction over parks and other Crown resources, and answers to those questions will reportedly be worked out over the course of a transition period. What will become of Naikoon Provincial Park on Haida Gwaii, for example, is one such question.

“I think there will likely be discussions with the Haida around how the parks are ultimately managed,” B.C. Environment Minister George Heyman told BIV.

“But they’ve given no indication that they want to change the fundamental nature of these being parks that are accessible,” he said. “We have a couple of other examples of First Nations where we reached reconciliation agreements, and part of the agreement was to give the nation essentially title over the park, but part of the agreement was that they continue to be operated in much the same way they have in the past.”

Agreement avoids having the courts decide title

Haida Gwaii’s geographic isolation makes it unique in B.C. No one contests the Haida Nation’s continuous and exclusive occupation of Haida Gwaii. Nor do the nation’s claims overlap with the claims of other nations—as is often the case with many other First Nations—so the Haida appear to have an even stronger case for proving title than did the Tsilhqot’in.

What has raised questions and concerns was Premier David Eby suggesting that this settlement agreement could become a template for other First Nations, and that it might serve as an alternative to formal treaty negotiations.

Asked by IndigiNews if the Haida approach could replace the treaty negotiation process, Eby said: “I think for some nations, this would be a preferable approach.”

What, then, is the approach?

“Premier Eby’s musing about the Haida agreement being a template suggests everyone in B.C. should ponder how this arrangement could affect them, if something similar is implemented where they live,” B.C. economist Jock Finlayson and lawyer Mary MacGregor recently wrote in a joint analysis for the Fraser Institute.

In an interview with BIV, Minister of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation Murray Rankin qualified the premier’s remarks, saying he had said it was a “template for the art of the possible.”

“The circumstances in Haida Gwaii are unique. Whether those can be replicated elsewhere will be determined over time,” Rankin said.

The law firm Fasken has noted the bilateral agreement between B.C. and the Haida “is a first-of-its-kind negotiated agreement that is not a treaty, but rather part of a reconciliation process, making its nature and effect legally uncertain.”

It also suggests that the agreement could create expectations among other First Nations seeking similar recognition.

“However unique the province may claim Haida is, other Indigenous governments will likely demand the same type of agreement,” Fasken noted.

Other recent decisions on the reconciliation front could add to concerns that the B.C. government—guided more by a United Nations declaration than by existing Canadian legal principles—may be willing to abridge the rights of non-Aboriginal citizens when trying to address and redress the rights of First Nations.

Three days after the Haida Title Agreement was introduced, B.C.’s Ministry of Environment announced it would close the popular provincial park Joffre Lakes to the general public for several weeks this year for the exclusive use of First Nations.

And earlier this year, the B.C. government came under fire for planned amendments to the Land Act that were intended to bring it in line with the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA).

The government moved to change the act to include consent-based agreements that would give First Nations co-decision-making powers with respect to land use in B.C.

The way in which the government rolled out the Land Act amendment process, without much transparency or forewarning, caused a backlash that forced the province to press pause on the initiative.

It is DRIPA—implemented in 2019—that some critics to point to when questioning some of the B.C. government’s recent initiatives.

“It was unclear at the time what it would mean for government policy, law and administrative practice in the future,” MacGregor and Finlayson write.

“But we’re beginning to see how B.C. policymakers plan to advance the goal of ‘reconciliation’ with Aboriginal peoples following the adoption of UNDRIP several years ago.”

Robin Junger, an Aboriginal law expert with McMillan, has criticized DRIPA and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP), on which it is based. He said Canadian law—Supreme Court of Canada rulings and Section 35 of the Constitution—provide all the guidance necessary for balancing Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal rights.

“The UN declaration does not require a balancing of interests like Canadian law does,” he said.

B.C.’s official opposition party BC United, which voted in favour of implementing DRIPA in 2019 and in favour of the Haida Recognition Act last year—called for the Haida Recognition Amendment Act (Bill 25) to be deemed an exposure draft, which would mean halting it at first reading until after the provincial election in October.

When Bill 25 was given first reading, there were only five weeks left in the B.C. Legislative session, and less than five months until the provincial election, said Michael Lee, BC United shadow critic for Indigenous relations and reconciliation.

“This is not the time to be doing this kind of fundamental change,” he said. “We need greater transparency, consultation and engagement.”

Can private land exist within Aboriginal title land?

In 2002, British Columbians who voted in a referendum on treaty negotiations made it clear they felt neither parks nor private lands should be on the table when negotiating modern treaties with First Nations.

It is unsurprising, then, that one of the biggest concerns about the Haida Title Lands Agreement is what it means for private landowners if the entirety of Haida Gwaii comes under Haida title and governance.

The Aboriginal law teams at two law firms—Cassels and McMillan—suggest Aboriginal title and fee simple land cannot co-exist.

Even the B.C. government’s own lawyers have characterized the notion of fee simple and title land co-existing an “absurdity.”

“The existing authority, which is approved by the Supreme Court of Canada, is the notion of Aboriginal title and fee simple title co-existing is an ‘absurdity,’” said one of the lawyers acting on behalf of the province during 2017 proceedings in the Haida-versus-B.C. case.

Aboriginal title land, as defined by the courts, is communal in nature.

“The rights in land which flow from both a fee simple interest and Aboriginal title interest (which is constitutionally defined and protected) include exclusive rights to use, occupy and manage lands,” writes Tom Isaac and Mackenzie Hayden at Cassels. “The two interests are fundamentally irreconcilable over the same piece of land.”

Merle Alexander, an Indigenous resource lawyer at law firm Miller Titerle, disagrees. He said the Haida Title Agreement resolves this conflict by simple agreement to allow private land to continue under provincial jurisdiction.

“It’s so glaringly clear that fee simple land rights are being protected,” he said. “It’s almost as if this idea comes from not even reading [the bill].

“I think the agreement itself actually tries to give greater certainty to fee simple holders, because the courts really haven’t given us a lot of guidance on this. I think, if you negotiate the actual framework, and you expressly and directly deal with fee simple interests, I think there’s much greater certainty to negotiated language.”

Geoff Plant, who was attorney general and treaty minister under the Gordon Campbell government, also said the agreement itself is quite clear on the protection of private, fee simple lands.

The Haida Title Lands Agreement itself states that: “The Haida Nation consents to and will honour fee simple interests, including those held by Haida citizens,” and that “the Haida Nation consents to fee simple interests on Haida Gwaii continuing under British Columbia jurisdiction.”

“It would be difficult to be any clearer than this,” Plant has written.

“You don’t need to be a lawyer to read plain English. To argue that this agreement somehow threatens fee simple property rights on Haida Gwaii is to misread the agreement.”

Rankin told BIV that 2.2 per cent of Haida Gwaii is fee simple land, and half of it is owned by the company Mosaic Forest Management.

“We’ve had many conversations with the mayors of the three main communities, and I can tell you there is an understanding that fee simple is not—repeat, not—on the table. It’s protected in perpetuity.”

But even if First Nations consent to honour fee simple lands, McMillan warns that private landowners may still be affected by how First Nations use their title and governance powers.

“Will the Haida Nation’s ability to regulate uses of private fee simple land be similar to local government’s zoning powers?” McMillan asked in its analysis. “If so, how will this reconcile with the local government powers? Will it matter that non-Haida residents cannot vote in Haida elections?”

McMillan pointed out that, while 95 per cent of the Haida approved of the Haida Title Agreement in a referendum, non-Haida citizens on Haida Gwaii were given no similar referendum vote.

“The government would be wise to answer the questions raised by Bill 25, instead of dismissing those who are posing them,” McGregor and Finlayson wrote.

“The province also needs to get serious about the difficult but necessary process of engaging in consultation and substantive dialogue with non-Aboriginal British Columbians on the broader push for reconciliation. Because B.C. is out there alone, nearing a point of no return on its fast-moving reconciliation agenda, one should not underestimate the harm that mismanaging these issues may cause.”