Pure electric cars, not to be confused with engine/electric hybrids, are gaining popularity these days in spite of such disadvantages as limited driving range, high cost and extra weight. The range is improving with more powerful batteries, and initial cost is partly offset by government grants.

But electrics are far from new, being present at the birth of the automobile at the end of the 19th century and continuing for a surprisingly long period.

When cars were in their infancy, electrics vied for supremacy with steam and gasoline engines. Each had advantages and disadvantages.

Electrics were clean, quiet and easy to drive, but their limited driving range made them essentially urban vehicles. Although steamers were quiet and powerful, they required a skilled operator and took time to generate steam. Gasoline cars were easier to operate than steam and had good driving range, but were noisy, sometimes cantankerous and had the onerous task of being crank-started.

When records started being kept, electrics held the world land speed record from December 1898 to April 1902. The highest speed attained was 105.9 km/h by Belgian Camille Janetzy on April 29, 1899, the first car to exceed 100 km/h.

That lasted three years until broken by a Serpollet steamer driven by Frenchman Leon Serpollet at 120.8 km/h on April 13, 1902.

A few months later, Serpollet’s record fell to W.K. Vanderbilt Jr., in a gasoline-powered French Mors at 122.5 km/h. All records after that went to gasoline cars until the advent of the 1960s “rocket cars.”

The arrival of the electric self-starter on the 1912 Cadillac was a watershed development. It eliminated the gasoline engine’s biggest disadvantage and enabled gasoline cars to surge ahead, although electrics would hold a tiny share of the market until the Second World War.

The longest running was the Detroit Electric, initially manufactured by the Anderson Carriage Co., founded by William C. Anderson.

Anderson was born in Milton, Ont., in 1853 and moved to Michigan as a boy. He founded Anderson Carriage Co. in Port Huron in 1884, relocating to Detroit in 1895. Noting the growing interest in horseless carriages, he began building his Detroit Electric automobiles in 1907, producing 126 chain-drive runabouts (open cars) that year.

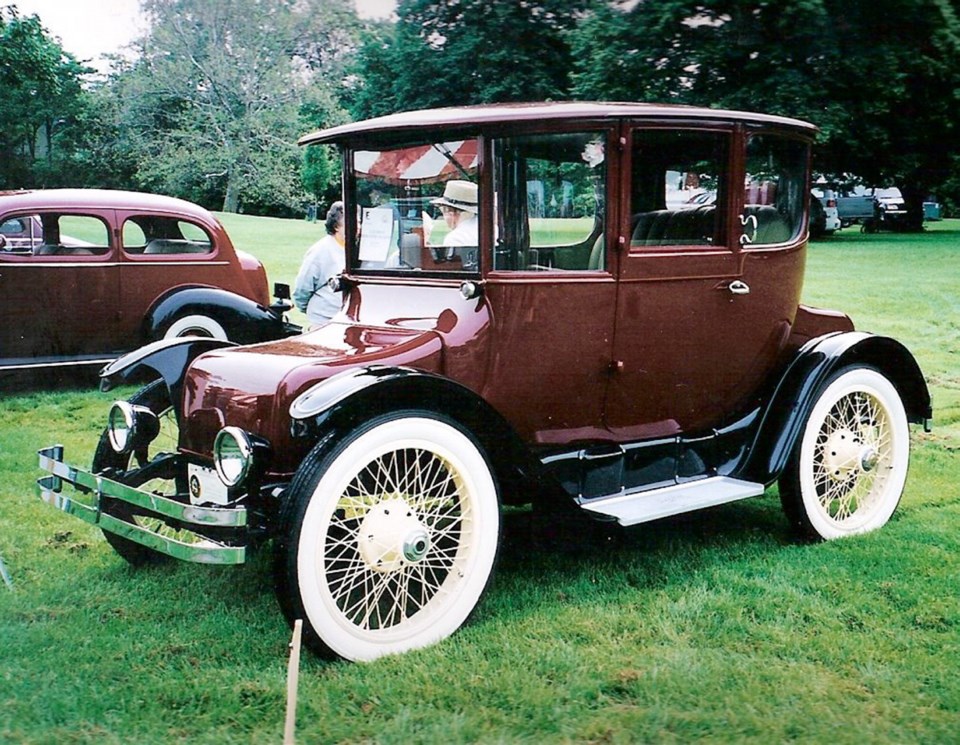

Anderson offered a closed Detroit in 1908, one of the first closed cars available. Called the Inside-Drive Coupe, it provided a cosy ride when most gasoline cars exposed passengers to the elements.

To gain control of its motor manufacturing, in 1909 Anderson bought Elwell-Parker Co., of Cleveland, which made motors for the Baker Electric. Anderson could now make almost everything for his cars.

Detroit Electrics established a reputation as well built and easy to drive. Production reached 400 in 1908, 650 in 1909 and 1,500 in 1910. While small compared with Ford’s 32,000 1910 gasoline cars and Buick’s 20,000, it was respectable for a gradually fading technology.

In 1911, the name changed to Anderson Electric Car Co., and Detroits went from chain drive to a shaft from a centrally located electric motor that was powered by batteries under the “hood” and in the trunk. It was capable of about 40 km/h and claimed a driving range of 130 km.

The handsome, beautifully constructed white ash frame bodies were covered with sheet aluminum. They had luxuriously finished interiors with silk brocade fabrics and deep, richly upholstered seats. Buyers specified silver or gold trim.

Although Detroits offered left-hand, right-hand and rear-seat drive, the most common layout had the driver on the left side. Control was through two horizontal levers — a longer steering lever for the right hand and shorter speed-control lever for the left. Detroits later changed to steering wheels. A foot pedal engaged the rear-wheel brakes, and pulling the speed-control lever back provided additional braking by a drum ahead of the motor.

Detroit Electrics survived in a world dominated by gasoline cars by offering a wide variety of models including taxis and limousines. By 1914, annual production was approximately 2,000.

The First World War’s gasoline shortage sent 1916 production to 3,000 and Detroit gained needed factory space by purchasing Walker Vehicle Co., builder of the Chicago electric car. This would give it some added publicity when Pope Pious X rode in a Chicago electric “Popemobile.”

In 1919 Anderson became the Detroit Electric Car Co., and when car sales flagged badly in the 1920s, it began concentrating on commercial vehicles.

After a blip in sales in 1930 and ’31, Detroit Electric saw steady decline. Although it lasted until the end of the decade and underwent another name change to the Detroit Electric Vehicle Manufacturing Co., in later years it built only to order, usually with Willy-Overland bodies.