Local governments want the province to help make building tiny homes easier.

Tobi Elliott, who advocates for tiny homes as an alternative and more affordable form of housing in rural and coastal communities, said they exist in a “regulatory grey area.”

“It’s tough to make defined calls on what is or is not appropriate,” said Elliott, a trustee for the Gabriola Island Local Trust Committee who lives in a tiny home on the island.

Until the pandemic hit, Elliott ran tiny home education workshops in rural communities around the province.

The need for more diverse housing options, particularly on the Gulf Islands, is high, because land is scarce and prices are rising, she said. Tiny homes can be a form of “missing middle” housing in rural communities like the Gulf Islands, Elliott said.

But building them can be difficult because the B.C. Building Code doesn’t directly address them and some of the standards are difficult to meet when building a tiny home, Elliott said.

The Union of B.C. Municipalities asked the province to review its code to recognize tiny homes and provide building requirements for them to make the process easier on local governments. The request came in resolutions from the 2022 UBCM convention and was initiated by the Regional District of Nanaimo and Oliver in the Interior.

A resolution from the Regional District of Nanaimo said the province struggles with a “critical lack of affordable and available housing,” and facilitating the building of tiny homes can help increase options.

In a response in February, the Ministry of Housing said the code has no limits on how small a house can be built as long as it meets minimum standards for protecting people and the environment. The code establishes minimum safety standards on structural integrity, smoke alarms, egress and ventilation.

“Reducing or removing these measures compromises the health and safety of building occupants,” the ministry said.

Several manufacturers in B.C. have successfully designed tiny homes that meet the code’s safety standards, it said.

Elliott said the province’s response is “unsatisfying,” but agreed it is technically possible to build a tiny home that meets the code. “But you have to be really creative and innovative, and not a lot of builders or designers have been successful,” she said. That makes it difficult for prospective tiny home owners to build their own homes.

Some of the challenges of building to code include minimum distances required between a fireplace or hot water heater and flammable materials, and emergency exit requirements that are difficult to meet in a small space, Elliott said.

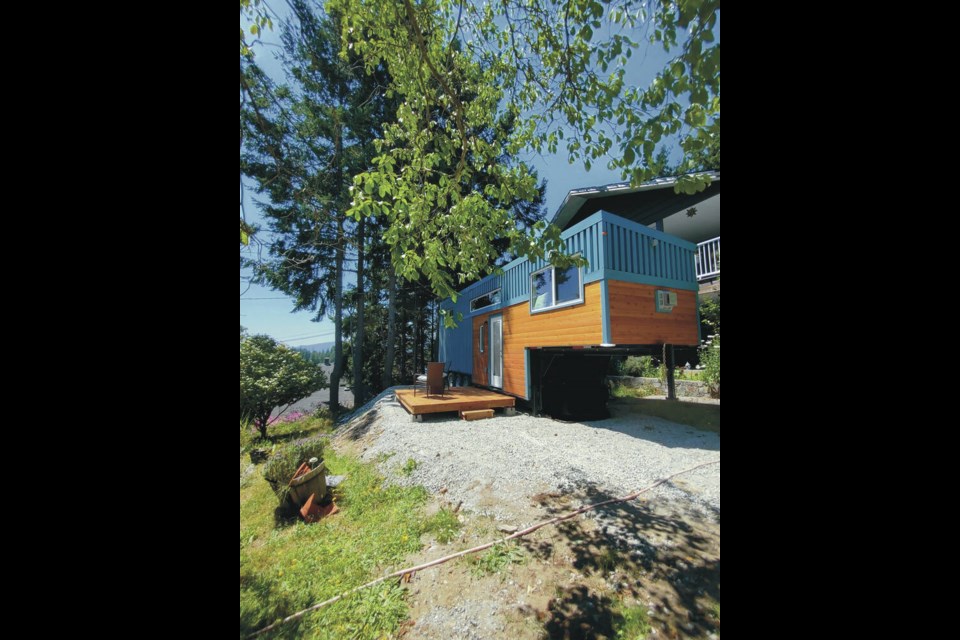

Pam Robertson, owner of Sunshine Tiny Homes on the Sunshine Coast, which builds and sells tiny homes, said tiny homes don’t quite fit under standards for manufactured homes or RV homes. Most companies build to RV standards, Robertson said.

But municipalities won’t recognize RVs as a primary, permanent residence, which can create problems for those living in them, such as with insurance. Because the homes exist in such a grey area, insurance companies are unsure how to handle them, and her clients have had quotes ranging from $800 to $3,000 per year for their tiny home, Robertson said.

“It’s never the same way twice for any of my clients,” she said.

Robertson has completed a tiny home build that meets standards for manufactured homes set out in the Canadian Standards Association. The cost is higher, but it can be recognized as a primary residence, she said. Still, there are challenges. She cannot advertise the loft in the home as a bedroom or sleeping area and, instead, has to call it a storage space, even though it meets egress requirements, she said.

Elliott said if the province doesn’t want to address tiny homes in the building code, the government could look to areas in the U.S. which allow third-party agencies to inspect and certify them.

“If they inspect your home and they give it the stamp of approval, then that would make it easier for building inspectors to be able to say: ‘Oh, this meets some kind of code, it meets a standard.’ So that would probably be the way forward,” she said.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]