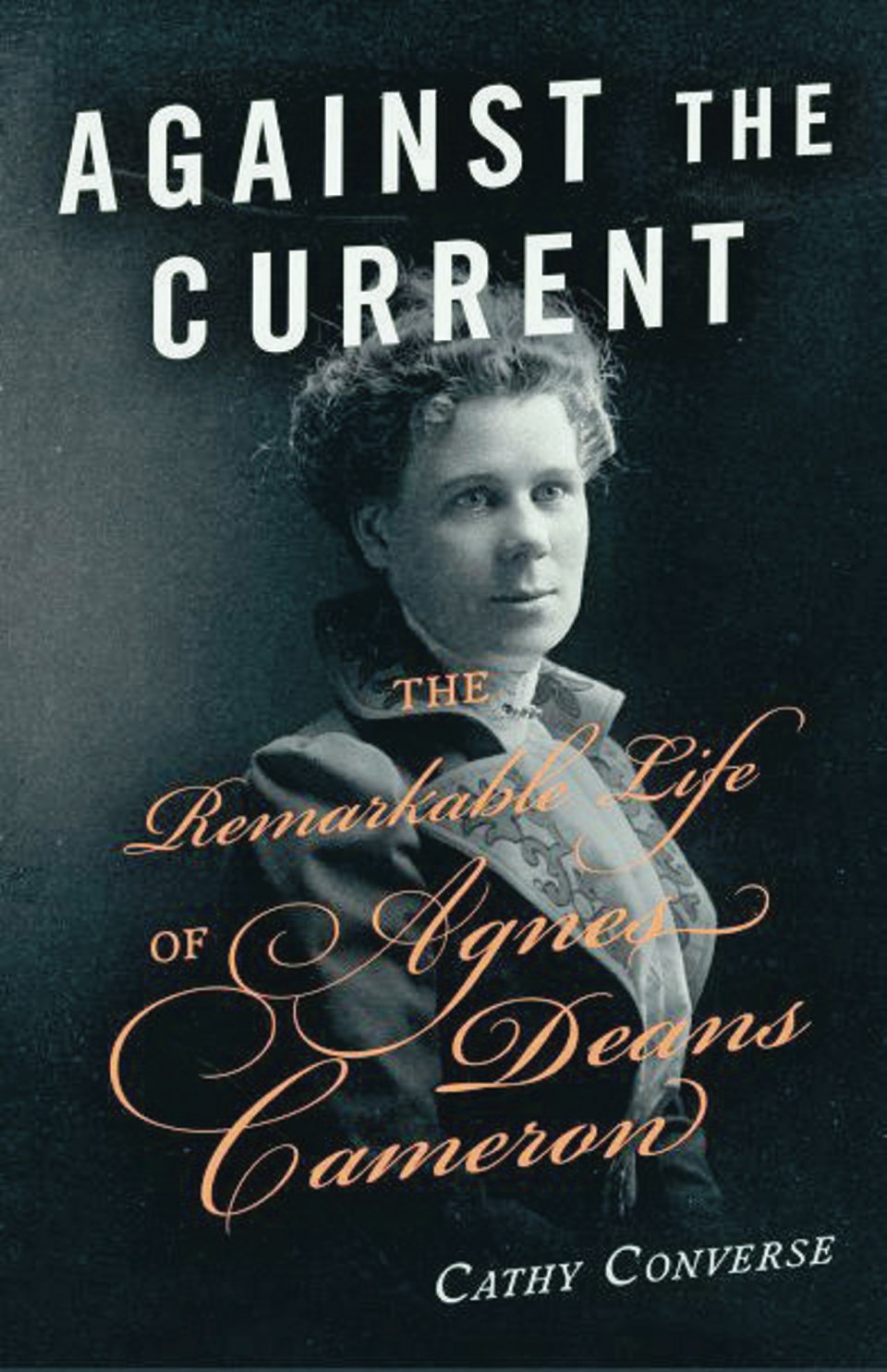

Against The Current: The Remarkable Life of Agnes Deans Cameron

By Cathy Converse

Touchwood, 296 pp., $30.

Agnes Deans Cameron truly was, as this book’s title suggests, a remarkable woman who helped shape our education system, helped prove that women could travel to the toughest places in the country and helped put realistic information about British Columbia into the hands of readers throughout North America.

All of that was crammed into a life of just 48 years.

Cameron was ahead of her time. She was the first female high-school teacher in the province, and in 1894 became the first female school principal.

She fought for the right of women to vote, a victory that was not won until after her death. She took a liking to bicycles, and this book is a reminder that clashes between cyclists and everyone else are nothing new.

Against the Current: The Remarkable Life of Agnes Deans Cameron by Cathy Converse is a long-overdue look at Cameron’s life.

Cameron was a tough teacher, using methods that would likely get her fired today. Remember that the strap was still used in B.C. schools into the 1970s, and Cameron taught 80 years before that.

In 1905, the school board fired Cameron after a dispute over the perceived failure of her students in drawing examinations. Along with the dismissal, Cameron’s teaching credentials were suspended for three years, effectively curtailing her ability to make a living.

The firing ended up in the courts, with plenty of attention from Victoria’s two daily newspapers, but Cameron was not able to retain her job.

The status of her job was just one of three battles Cameron was fighting at one time. Her mother Jessie was dying, and Cameron was fighting an ultimately losing battle to retain her house, at the time the oldest in Victoria, against a plan to extend Government Street.

Soon after losing her job, Cameron was elected a school trustee, but resigned the position a few months later after missing two meetings. She left Victoria for a life of adventure and productivity elsewhere.

She became known across the continent as a writer, with her work appearing in esteemed publications such as the Saturday Evening Post.

“Because of Cameron, England, the United States, along with the rest of Canada, learned about the western and northern part of the Dominion, showcasing a complex and varied geography and population,” Converse writes.

Against the Current helps the reader visualize life in early Victoria, describing the muddy streets and even the smells.

At times, however, the detail can be distracting. Was Converse fleshing out the story of Cameron’s life, or was she filling in gaps because of a lack of information about Cameron? It can be hard to tell.

As with many books on local history, this one would have been better with more maps. There is one that shows her route to and from the Arctic, but what about the location of her family home in Victoria? The location clearly mattered, since the fight over it was a pivotal part of Cameron’s life.

Despite her many successes, Cameron has not received the recognition she deserves; to this day, a woman standing up to authority seems to be a problem. This book helps to bridge the oversight by giving Cameron the credit she deserves.

And now, what about other trailblazing women, such as Maria Grant and Rosalind Young? Both women made great strides in a world dominated by men, just as Cameron did.

Against the Current whets the appetite. More, please, more.