Churchill and Fisher: The Titans at the Admiralty who fought the First World War

By Barry Gough

James Lorimer, 600 pp., $39.95

Victoria historian Barry Gough has been setting the world on fire, one might say, with his remarkable string of books on history, a strong reflection of a lifetime devoted to probing deeper and deeper into the past.

It’s not just the number of books that makes Gough notable, it is the range of topics. From Victoria High School to the early maritime history of the Pacific coast to Winston Churchill, Gough’s range is breathtaking.

It’s not easy to average a book a year on similar topics, but it can be done. To have a series of books on widely differing topics is next to impossible, something that nobody bothered to tell Gough.

His books are highly acclaimed; Gough is considered one of the leading authorities on the history of the Royal Navy.

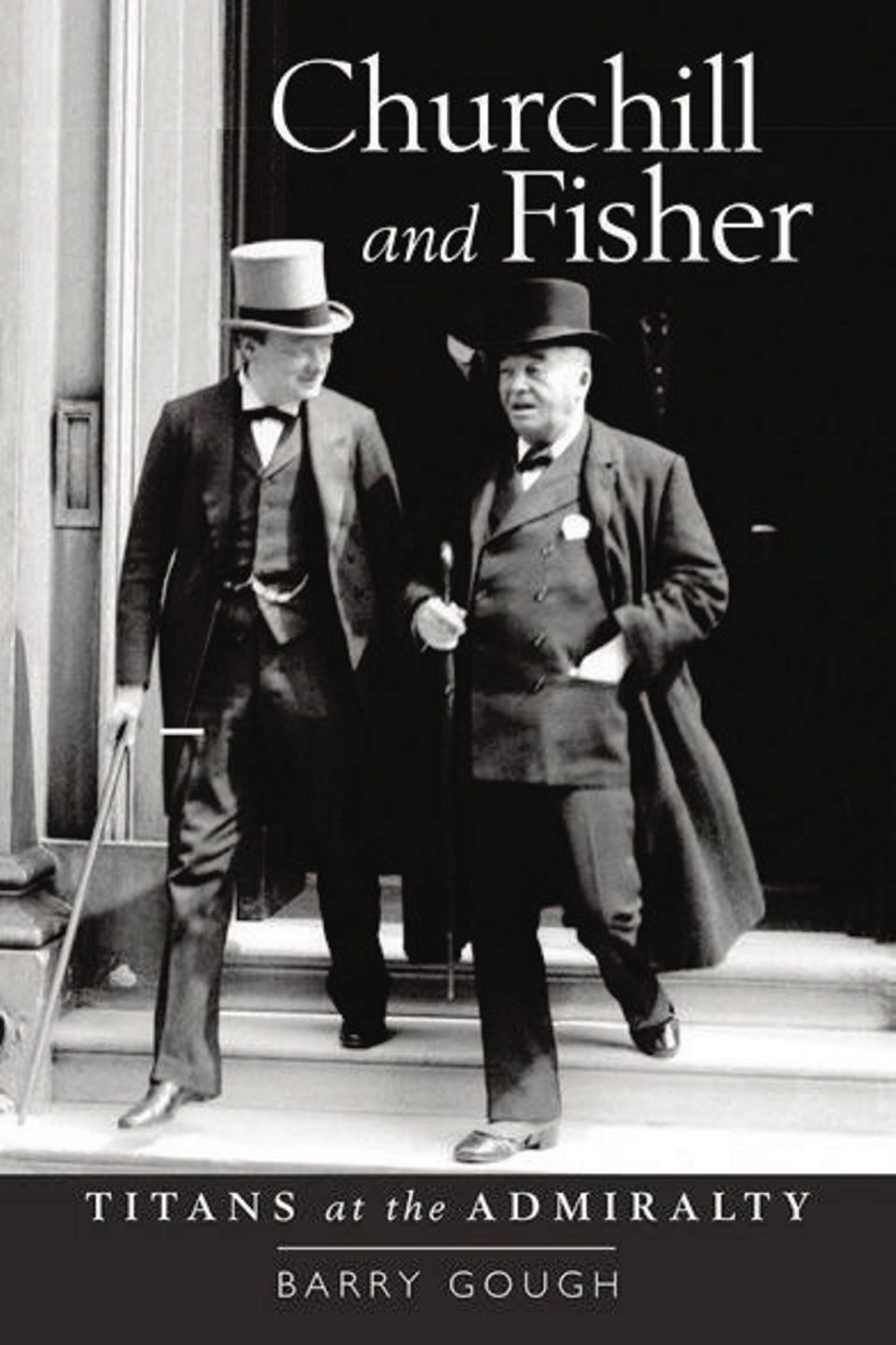

Churchill and Fisher is an exhaustive account of the careers of two men who came together to help lead the United Kingdom’s fight in the First World War.

Admiral Jacky Fisher had already left a huge mark on the navy as the person who introduced dreadnoughts to the fleet. These heavily armed ships became the standard battleship design during the First World War.

Fisher also left his mark on Greater Victoria. His efforts to reshape the navy included a strong commitment to redeploy resources closer to the British Isles, which meant pulling back from bases in the far reaches of the world.

In 1904, a government report said there would be economic advantages in closing five overseas stations, including Halifax and Esquimalt in Canada.

The argument for closing Esquimalt was simple: Advances in technology and transportation, as well as a major rethinking in politics, had effectively made it redundant.

The base could not hold off an attack from the Americans, and such an attack was considered unlikely in any event. Troops could be sent to the Pacific coast from eastern Canada within six days, from Hong Kong in 20 days, and from Great Britain in 26 days, including seven for preparation.

On March 1, 1905, the Pacific station at Esquimalt was closed, with its munitions and stores transferred to Hong Kong. By 1908, only two sloops and a survey ship were still based at Esquimalt, and in 1910 the base became part of the new Canadian naval service.

Four years later, war broke out, and Churchill and Fisher played important roles in the Admiralty. Both men were tough, demanding, impatient leaders, and although they were not easy to deal with, they earned the respect of those who reported to them.

Fisher was 74 years old when Churchill, as first lord of the admiralty, brought him back to help with the war effort. Together, they were a formidable force leading the British naval forces.

The war came to the Pacific in November 1914, at the misguided battle at Coronel off the coast of Chile. Four hopelessly mismatched British ships engaged a German squadron, and the battle ended with the loss of two of the British ships, as well as 1,600 men. It was the first British naval defeat in more than 100 years.

The following May brought the sinking of the Lusitania passenger ship off Ireland, with the loss of 1,198 people, including several from Victoria. The Admiralty, under Fisher and Churchill, came under fire in the House of Commons for neglect.

Both men blamed the captain of the Lusitania for the sinking, actions that Gough says “smack of dishonour.” It is clear that there was plenty of blame to go around.

Soon, both men were gone from the Admiralty. Fisher resigned to protest Churchill’s continued interference in his work, and then Churchill was demoted.

The two men had had a huge impact in the early years of the war, but their departure was inevitable from the start. They were both firm in the belief that they were right, and Churchill’s refusal to consult with the much more experienced Fisher on key decisions drove him out — although Fisher himself was not without fault.

The tremendous power wielded by these two incompatible leaders is a key part of the story of the First World War, and Gough’s comprehensive Churchill and Fisher will help to bring it to a wider audience.

The reviewer is the editor and publisher of the Times Colonist.