The Financial Services Regulatory Authority of Ontario has announced that as of June 1, insurance companies are no longer allowed to sell segregated funds with deferred sales charges.

This decision will bring the regulation of segregated funds in line with the regulation of mutual funds, for which DSCs were banned on June 1, 2022, after a prolonged period of consultation with industry groups, regulators and investors. It is expected that other provincial and national regulators will follow Ontario’s lead soon.

The FRSA also said that they are planning to launch consultations on another regulatory change that would address concerns regarding DSCs in segregated funds that have already been sold.

“Consumers deserve to have access to their own investments,” Huston Loke, executive vice-president of market conduct at FSRA, said in a statement. “When people have to pay to withdraw their own money from segregated funds, they feel they are being cheated. We’ve now banned these charges on new sales to better protect consumers.”

Insurance licence

When we meet with prospects who have segregated funds in their portfolio, we will first explain to them the licensing component of financial professionals.

Insurance advisers that only have an insurance license are limited on the investment options that they are permitted to discuss, purchase and sell. The three main types of investment insurance products are: segregated funds, guaranteed insurance contracts (GICs), and annuities. They cannot sell other securities that trade on a stock exchange (individual stocks) or even sell investments that trade under a traditional prospectus (i.e. regular mutual funds). We explain this to the prospect because the individual they are working with may be limited to selling insurance products (if they are licensed only as an insurance adviser).

In our opinion, individuals looking for investment advice should always work with either a wealth adviser or a Portfolio Manager who has the option to offer all types of securities. (As we’ve noted previously, some wealth advisers and portfolio managers also have their insurance license — essentially, they do not have the same limitations.)

What is a segregated fund?

The best way to understand segregated funds is to compare them to mutual funds. Like mutual funds, various clients’ capital is pooled together and invested by an insurance company. Segregated funds are an insurance contract issued by an insurance company and are regulated by the Insurance Act, as opposed to securities legislation.

There are a few differences that are worth highlighting. The first is that the management expense ratio is significantly higher. Mutual funds are already criticized for the higher costs; segregated funds are even higher than mutual funds.

The second is that they are considered an insurance contract and beneficiaries can be named. This is more important for clients that have a non-registered account where a traditional investment account (not insurance) can not name a beneficiary.

The third difference is that segregated funds include guarantees to the original investment. There are two types of guarantees: death benefit guarantee and maturity guarantee.

Death benefit guarantee

The death benefit guarantee provides that the named beneficiaries will receive either the market value of the investments or a stated percentage of the original principal invested, whichever is higher, in the event of death of the investor.

Segregated funds must provide at least a 75 per cent death benefit guarantee, but the guarantee can be up to 100 per cent. The higher the guarantee, the greater the management expense ratio.

The biggest component that has changed over the years with death benefit guarantees and segregated funds is the age restriction on when they can be purchased.

For example, when I first became insurance licensed nearly two decades ago, segregated funds could be purchased for individuals who had not yet reached their 90th birthday with a 100 per cent guarantee with no asset mix restrictions. This enabled individuals to invest in a 100 per cent equity segregated fund and have the potential upside (with higher costs), with full protection for the downside (100 per cent guarantee of the original investment) if they passed away.

Over the years, insurance companies have made changes such as only offering 75 per cent guarantees or limiting the investment options (i.e. having a more conservative portfolio) for older clients with 100 per cent guarantees, depending on the insurer. A lot of the changes have made these investments less attractive than in the past.

The maturity guarantee

The maturity guarantee provides that the investor will receive between 75 and 100 per cent of the original deposit at maturity of the contract (usually 10years), even if the market value of the investments declined. As noted above, the added insurance component with segregated funds comes with a higher daily management expense ratio than comparable mutual funds (that do not have the guarantees).

In our opinion, a 100 per cent guarantee after 10 years is very weak. Using the rule of 72 as a guide, if your capital was earning 7.2 per cent a year, your capital should have doubled during that same period — giving significantly more than just receiving your original funds back.

Fees to purchase segregated funds

When an investor decides that they want to purchase a segregated fund, there are a few ways to purchase them. The most common ways are initial sales charge (ISC) and deferred sales charge (DSC).

With the ISC, an adviser has the option to negotiate the fee, which can be anywhere from zero per cent up to five per cent. This fee is paid to the adviser’s firm at the time of purchase.

With the DSC option, the fee is paid by the investor to the adviser or investment firm when they sell a fund. This can be based on the original cost of the fund or the current value (depending on the firm) and how long they were held.

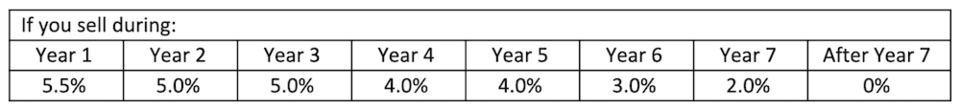

A DSC is typically a percentage that is charged if an investor decides to sell their investment within a certain time period. This percentage declines over time to zero, encouraging investors to remain invested. DSC’s can result in hefty commissions for investors who decide to change their mind and sell their investment within the first few years after buying it. A DSC schedule might look similar to this:

So, let’s assume Jane decides that she wants to sell her segregated fund that she bought on a DSC basis. Jane has held the fund for three years and originally invested $500,000. Based on the schedule above, Jane would have to pay five per cent based on the original cost — $25,000. If the current market value of the fund was $525,000, then Jane would only receive $500,000 ($525,000 - $25,000).

Now let’s assume that Jane is selling the fund because of poor performance. If the current market value was $475,000, then she still must pay the $25,000 (five per cent of the original $500,000 even though it’s declined, leaving her with $450,000. That is because this fund’s DSC schedule is based on the original cost of the investment.

To put this another way, on the day that Jane purchased this fund, her insurance adviser was paid $25,000 in commissions from the insurance company and was immediately locked into the DSC schedule.

Higher ongoing fees

Compared with mutual funds, the segregated funds MER tends to be significantly higher given the insurance features like the death benefit guarantee and the maturity guarantee.

Both segregated funds and mutual funds have similar structures when it comes to their ongoing fees. We wrote an article back in 2020 describing why we avoid mutual funds and one of the reasons is the initial fees, ongoing fees, and different layers of embedded fees. My investment approach is to avoid mutual funds .

There are two broad types of fees for the ongoing management of segregated funds:

• Management expense ratio (MER)

• Trading expense ratio (TER)

The TER represents the amount of trading commissions incurred when the portfolio management team buys and sells assets within a given fund.

The MER, on the other hand, is made up of several components. It includes the trailing commission, investment management fee, operating costs, and taxes. MERs for segregated funds vary and can be as high as 2.93 per cent for a Canadian Stock Fund or 3.86 per cent for a Special Situations Fund. The trailing commission is an ongoing charge for services and advice provided by your advisor and their firm, and usually varies between 0.25 per cent and 1 per cent.

All of the various fees have a direct impact on a client’s performance.

We are very happy to see regulators are taking another step toward protecting investors, and hope that other provincial regulators announce similar changes in the following months. We also hope that new rules are put in place soon to protect investors who have already bought segregated funds with DSCs. We look forward to DSCs being a thing of the past.

Kevin Greenard CPA CA FMA CFP CIM is a Portfolio Manager and Senior Wealth Advisor with The Greenard Group at Scotia Wealth Management in Victoria. His column appears every week at timecolonist.com. Call 250-389-2138. greenardgroup.com