B.C. embarked on a first-in-Canada experiment at the beginning of this year, decriminalizing small amounts of certain drugs in an effort to realign its response to the toxic drug poisoning crisis toward a health-oriented approach.

Six months later, the reviews are mixed.

While police seizures and arrests for simple drug possession are trending down, critics say the pilot project is only of limited help in addressing the province’s climbing overdose death toll — 11,171 since a public emergency was declared in 2016.

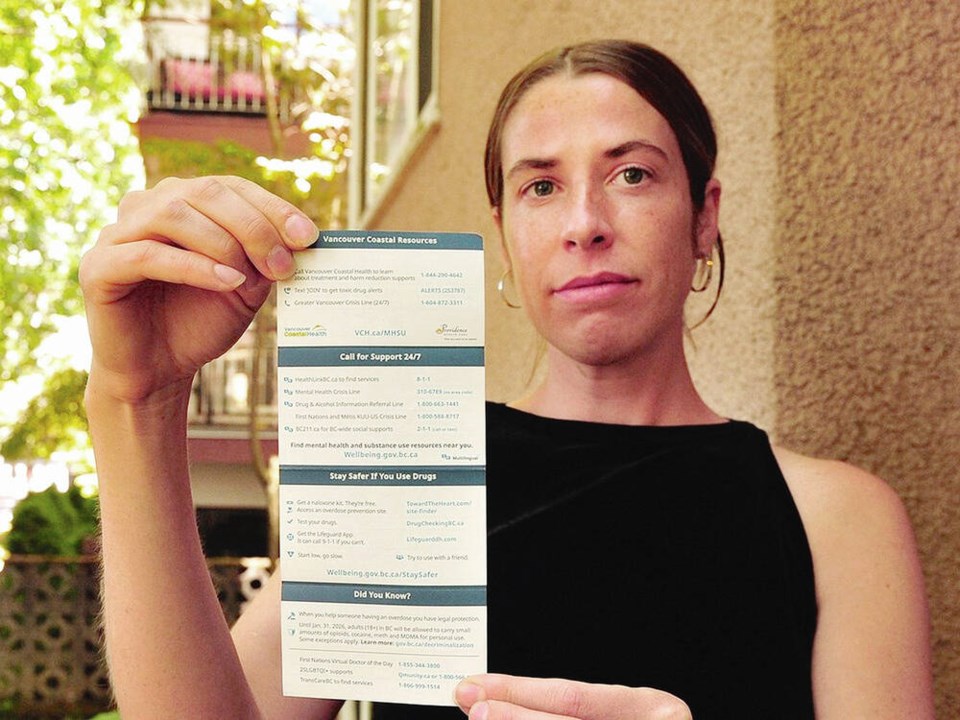

Instead of administering handcuffs, police are now trained to offer wallet-sized “health service referral cards” that list phone numbers for treatment in their region to adults found with up to 2.5 grams of opioids, cocaine, methamphetamine or MDMA.

But what some law enforcement, drug users and researchers say is still needed to bridge the gap between those found with the drugs and the help they are being encouraged to seek is an expansion of publicly funded treatment and services.

Only 3,237 publicly funded community substance use treatment beds exist in the province — even though an estimated 100,000 residents have been diagnosed with opioid use disorder, according to B.C. Centre for Disease Control figures.

Not everyone found with drugs on them is happy to be receiving health resource cards, of which 140,000 were printed and distributed to police agencies in B.C.

Garth Mullins, a Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users organizer who has spent time in jail on heroin possession charges, said the last thing he would do is accept a handout from police.

“Getting our drugs seized and being arrested has been ruining our lives for decades,” said Mullins, who described his journey with substance use treatment as riddled with barriers, including long waitlists.

“I had to wait and call every day to try to get into a detox. Once you’ve done that, you’ve got to do the same thing to get into a treatment centre that doesn’t cost you thousands out of your own pocket,” he said.

But Mike Serr, chief of the Abbotsford Police Department and member of B.C.’s core planning table on decriminalization, believes the reason some individuals are not accepting health referral cards is because “they are not ready to accept help.”

There is currently no indication how many cards police have been distributed or whether any of them have been used to make a successful referral to treatment.

While a B.C. Ministry of Mental Health Addictions training manual obtained by Postmedia through a freedom-of-information request recommends officers “document that a resource card was offered and whether it was accepted it not,” the strategy is not being tracked.

When Postmedia inquired about the measure in early July, the province said in a statement: “So as not to incentivize the distribution of resource cards unless required, police were not asked to track the number of cards they hand out.

“Instead, the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions and health authorities are closely tracking the bulk number of cards that are distributed to RCMP districts and municipal detachments in each region.”

Asked whether the health resource cards have led to increased calls for help, Vancouver Coastal Health said, “evaluation of the pilot is being conducted provincially.”

Fraser Health said it is also not tracking whether resource cards are leading to referrals to its Virtual Care Line.

“The resource card is a new initiative and we are continuing to work with our partners to improve access to substance use treatment services throughout the Fraser Health region,” said spokesperson Dixon Tam.

Some municipal and police leaders say decriminalization has left them with a new public safety issue: people consuming drugs in public spaces near children.

“Parents are calling us frustrated to be getting a waft of crack smoke in their face while they’re out for a walk with their kids,” Serr said.

Police no longer have the means to remove drug use from “inappropriate” public spaces such as playgrounds and recreation centres, he said. That is because prior to decriminalization, officers relied on drug seizures and arrests as “a tool” to manage public drug use near children.

“Police would always try to direct people to a safer location, but if they were defiant and didn’t move, then we would take their drugs.”

B.C. is consulting municipalities on the matter, with new public consumption limits expected in the fall. Municipalities including Campbell River and Port Coquitlam have already passed bylaws that ban drug use at city parks, playgrounds and recreation centres.

But legal advocates have expressed concern that a crackdown on public drug use could ruin the intent behind decriminalization — to reduce stigma that has prevented people from accessing life-saving supports and services.

“We didn’t want to see people who have historically been criminalized the most for drug use — such as those living in poverty, the unhoused and people of colour — pushed further out of sight, because it could increase their chances of dying from a toxic drug overdose,” said Caitlin Shane, a lawyer with Pivot Legal Society.

Shane is among those asking the province to stand behind its current decriminalization model, which only lists airports, child-care facilities and schools as places where possessing small amounts of drugs remains illegal.

Kora DeBeck, a research scientist with B.C.’s Centre for Substance Use, says a key measure of success of the pilot project will be whether there is a notable decline in police seizures of drugs, arrests and charges.

“When people have their drugs taken away, it is a traumatic experience for them,” DeBeck said. “Many say they feel rushed to find a new supply of drugs and use without first testing them or utilizing harm-reduction equipment, which increases their risk of blood-borne infections.”

DeBeck said decriminalization only has the power to impact public perception of drug use, by limiting the interactions between police and drug users.

“Decriminalization is not poised to have a big impact on overdose fatalities — because the majority of deaths are occurring most often out of the public eye in private homes due solely to B.C.’s toxic drug supply.”

The province says it plans to release figures in the next few weeks measuring decriminalization’s outcomes with police drug seizure, arrests and charge data, figures of overdose deaths, and surveys from police training and clients of harm-reduction services.

“The federal and provincial governments are working closely to evaluate and monitor the exemption to ensure it is meeting the desired outcomes of decriminalization and there are no unintended consequences,” the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions said in an email.

Decriminalization has already begun to show positive signs in Delta, where police have reported 20 per cent fewer interactions for drug possession since the project went into effect, compared to those same six months in 2022.

Delta police’s interactions for drug possession declined from 50 between January and July last year to 10 during the same time this year. Drug seizures also dropped from 29 to nine.

“We have not recommended charges for any drug possession or trafficking offences in the 2023 period,” said acting Insp. James Sandberg.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]