A B.C. psychiatrist said she believes hospital physicians are “actively avoiding” speaking to families and care providers about people brought to hospital under the Mental Health Act, which is why she supports efforts by a B.C. Liberal MLA to require better communication before deciding whether to admit someone involuntarily.

Dr. Diane McIntosh, a psychiatrist and advocate for improved mental health care, has long been frustrated by the lack of dialogue between hospital physicians and patients’ mental health care providers.

“One of the reasons I became a very burned-out psychiatrist several years ago was because I would send a patient to hospital — and the last thing on earth that I want to do is send a patient to hospital, I have to be really, really worried about them — and invariably, no one would ever call me, and they would be just simply be discharged,” McIntosh said, adding that she is exasperated by B.C.’s “imploding” mental health system.

“Here we have a life-or-death situation and families are dismissed, not heard, and … actively avoided, in my mind,” she said.

Elenore Sturko, B.C. Liberal critic for mental health and addictions, on Wednesday introduced a private member’s bill that would require hospital staff to seek more information from relatives or care providers before deciding whether a person should be involuntarily admitted under the Mental Health Act.

The bill would amend Section 28 of the Mental Health Act to require doctors and nurse practitioners to make “reasonable attempts” to contact the family or care providers of those brought to hospital by police because they are believed to be a danger to themselves or others.

Jonny Morris, CEO of the B.C. branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association, applauded Sturko’s efforts to prevent suicides by people in mental health crisis after a visit to hospital.

“We need a greater focus on family involvement in care where appropriate,” said Morris, who has heard from families who want more input on whether a loved one is admitted to hospital under the Mental Health Act.

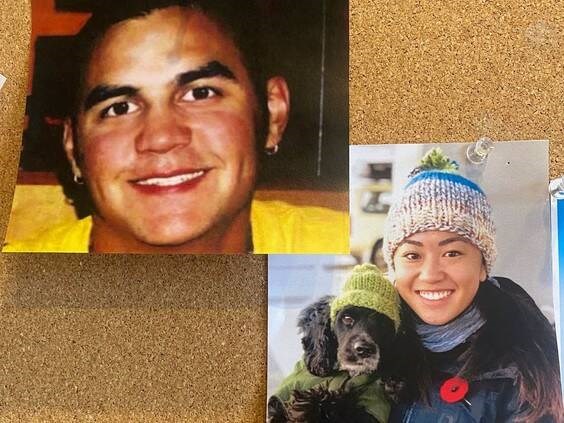

The bill was endorsed by the families of Todd Marr and Vancouver police Const. Nicole Chan, both of whom died by suicide a day after being discharged from hospital.

Marr’s parents, Lorraine and Chuck, and Chan’s sister, Jenn Chan, stood beside Sturko during a news conference at the legislature on Wednesday and tearfully pleaded for bipartisan support for the bill, which includes reforms that they are convinced could have saved their loved ones and might prevent future deaths.

Morris said there have been several coroner’s inquests into the deaths of people who took their own lives after being discharged from hospital. He cited the case of 38-year-old Eddie Young, who was discharged from Burnaby Hospital and immediately died by suicide. Staff did not notify his mother, Kim Young, that he was being discharged despite her pleas they do so.

Under the Mental Health Act, the director of a mental health facility must send notice to a “near relative” immediately after a patient’s admission, discharge, or an application to extend the person’s hospital stay. That rarely happens, McIntosh said, which has “resulted in many, many, many deaths.”

Jenn Chan said if she was told her sister was being discharged from Vancouver General Hospital two hours after being apprehended under the Mental Health Act, she would have checked in on her. Chan died by suicide on Jan. 27, 2019, after she alleged improper conduct, including sexual harassment and assault, against three male colleagues.

The jury in a coroner’s inquest made 12 recommendations, including better communication between community health providers, police and paramedics and the hospital physician treating the person in mental health crisis.

“I think if there was more information and communication between different parties … she might have been kept a little bit longer and her life might have been saved,” Jenn Chan said during the news conference Wednesday. “So I’m hoping this [bill] can prevent future deaths and other people having to go through what we’re going through.”

Todd Marr jumped to his death from an overpass on Sept. 9, 2009. The day before, his mother, Lorraine Marr, took the 32-year-old stonemason to Langley Memorial Hospital hoping he could get a psychiatric assessment for his suicidal thoughts.

She said the hospital staff did not talk to her about her son. If they had, she would have told them he tried to take his life the previous day.

Sturko was one of the RCMP officers who responded to the scene where Marr died. Sturko, who left the RCMP last year when she was elected to represent Surrey South, struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder and flashes of anger at the health system for not holding Marr involuntarily when he was in crisis.

Asked about the private member’s bill, Premier David Eby thanked Sturko for “giving voice to the concern of these families.”

Eby said he shares that concern and will take every opportunity to improve the “information that’s available to physicians or nurses when they’re making that incredibly difficult decision about whether or not to hospitalize someone who is in crisis.”

The situation is complicated, he said, and changes need to be made carefully to ensure there are no unintended consequences.

Mental Health and Addictions Minister Jennifer Whiteside said her office will be talking to health authorities, front-line providers and physicians with respect to what the practices are, “so that we understand precisely what they are dealing with in those interactions with patients.”

Private member’s bills are rarely passed by the government, but B.C. Green party MLA Adam Olsen urged the NDP to at least call it for debate.

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, call 1-800-784-2433 (1-800-SUICIDE), or call your local crisis centre. Help is available in over 140 languages. You can also reach the mental-health support line at 310-6789 (no area code needed).