The following excerpt from Pat Kramer’s popular history of totem poles traces the emergence of the poles on the Northwest Coast to the start of the sea otter trade with Europe around 1780. Over the next decades, as indigenous communities gained wealth and acquired new materials and techniques, local artists could experiment with producing their centuries-old traditions of mask- and crest-carving on a much larger scale.

American, British, French, Spanish and Italian ships all plied the waters along North America’s Pacific coast during the heyday of the sea otter trade. Though many forays arrived between 1780 and 1830, these naval traders did not always venture into the villages. Many preferred to remain on board, trading from the quiet security of their ships.

However, the trade process had an effect on the native communities. With the sudden increase in wealth and goods, and an abundance of new metal tools, tradition dictated a corresponding need for the upper classes to mount potlatch feasts. Each chief strained to outdo his rivals in terms of grandeur, honours, memorials, remembrances and ceremonials. Researchers speculate that totem poles, as they are known today, evolved during this period.

In 1786, the La Pérouse expedition visited the Tlingit people at Lituya Bay, Alaska. Though they travelled with an artist, there is no mention of totem poles. In 1787, Captain George Dixon visited the native people at Yakutat Bay in Alaska and on Haida Gwaii. Though his artist recorded details of native spoons and trays, there is no mention of totem poles.

However, only a few years later, in 1791, Spanish artist José Cardero, a member of the Italian Malaspina expedition, made drawings of several mortuary figures in the same village. Potlatch feasts of the day included the carving and dedication of memorials. This might explain the sudden appearance of the figures.

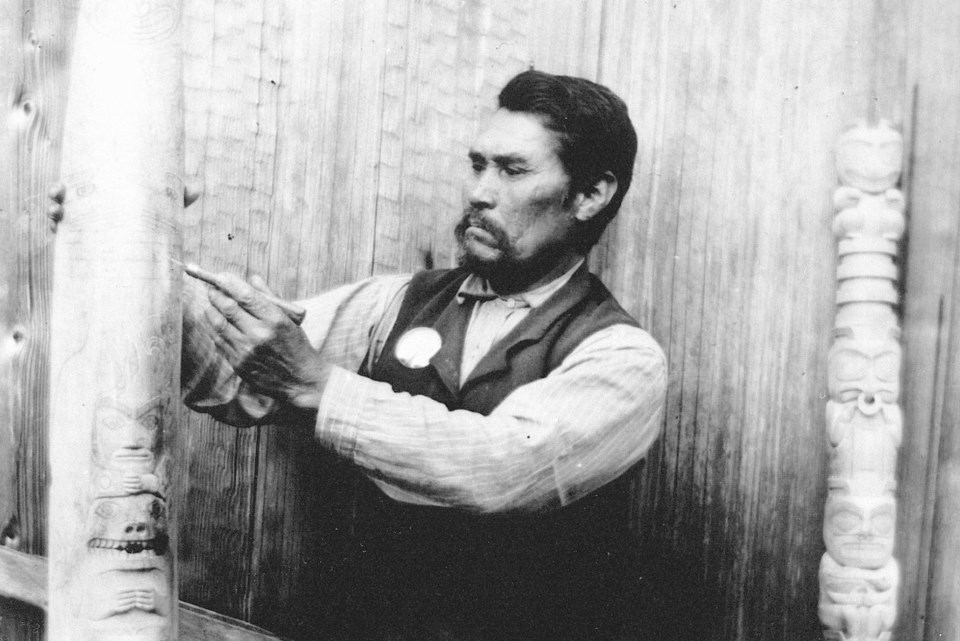

Techniques in handling large logs rapidly improved with the introduction of iron. Native people used new metal parts to fashion tools such as the axe, adze and curved knife following the form of their earlier implements. Their art forms, story figures and heraldic crest traditions were already many centuries old and well developed. The new tools were used to produce traditional art forms on a larger scale.

John Jewitt, a sailor captured in 1788, was forced into slavery by the Nootka people. He later escaped and in 1791 wrote a book — a bestseller in Europe. His writings talk of “great wooden images” on Graham Island and of “large trees carved and painted.”

John Barlett, artist aboard the Gustavus in 1791, made the first rough pen drawing of an outdoor heraldic pole. It is a house support in front of a Haida longhouse. This adds the second bit of visual information showing that house-front poles were under construction among the Haida people.

Clearly, widespread potlatching was afoot. Since iron tools made wood carving simpler and faster, and since newfound wealth made necessary the giving of potlatches, the beams of longhouses began to show more decoration both inside and outside, new forms of carvings were produced, and new surnames, new ceremonials, and new crests were sanctified. However, the right to give a potlatch and to own heraldic crests remained firmly in the hands of a few upper-class elders.

Meanwhile, in 1793, Alexander Mackenzie arrived on the Pacific coast. Having made the first overland trek across what is now Canada on foot and by canoe (a decade before the famed Lewis and Clark expedition), his report makes no mention of totem poles among the Bella Coola people. He did, however, report that some people decorated their interior house posts. Mackenzie was surprised by the number of iron pots and tools the natives owned.

In 1792, only one year earlier, Capt. George Vancouver reported seeing many gigantic wooden human mortuary statues. That same year, Etienne Marchand, leading a French sailing expedition, reported “paintings everywhere, everywhere sculpture, among a nation of hunters.” He also reported that “every man is a painter or a sculptor.”

In 1794, resourceful U.S. Captain Roberts of the Jefferson commanded his own carpenters and crew to plane, paint and erect a freestanding imitation “totem pole” of their own on the tip of Dall Island. Though they erected the structure to aid in their trade negotiations, there is no written report of the Haida reaction to the first non-native simulated pole.

In 1799, American William Sturgis visited the Haida in the vessel Eliza. He reported the Haida’s love of ornamentation in every aspect of their life, from their clothing to elaborately painted designs inside and outside their longhouses. He makes no mention of interior or exterior totem poles, leading historians to speculate that while tall poles did exist, they were still not common in all the villages.

By 1800, mortuary carvings were being consistently reported, not only in Haida Gwaii, but sporadically for 1,500 kilometres up and down the West Coast. Furthermore, the carvings seemed to be more numerous and more elaborate with each passing season. From 1803 to 1805, a Russian expedition under the command of Captains Krusenstern and Liansky packed up a significant collection of Tlingit art and removed it to St. Petersburg. It is not known whether these articles survived later Russian upheavals.

The first documented date known to outsiders involving the formal adoption of totem crests is 1808. A party of inland Gitksan natives celebrated their recent visit to the new Fort St. James fur-trading post by adopting crests and building a detached totem pole. That particular totem pole featured representations of European breeds of dogs, the fortified fort and wide wagon roads.

While it was not the Gitksan’s first freestanding pole, scholars disagree on when the people of the Skeena and Nass rivers started building detached poles. Some guess as early as 1775, though by following the path of iron tools that date could be some decades later.

In 1820, a black soft stone called argillite was discovered (or revealed to the outside world) at Slatechuck Mountain on Haida Gwaii. With the sea otter trade in rapid decline, the Haida eagerly began to fashion the material into carved pipes, bowls and small copies of totem poles.

Curio dealers, just beginning to discover the beauty of West Coast art, snapped up the items from mariners. As soon as argillite items were put up for sale in 1826, a Finnish trader in the service of a Russian-American company assembled a collection and sent it back to Finland. Sadly, the assemblage was later destroyed in a museum fire.

Though the objects were made strictly for sale to outsiders, argillite subjects are based on ancient traditions and are closer to the size and scale of native art before contact. In 1822, artist Ludovic Choris, who had travelled on a 15-year voyage around the world, published, in Paris, a detailed drawing of an intricate Haida argillite Raven tongue-thrusting pipe. His illustration is significant because it is the first to show the intricacy of design so well developed among the people.

From 1830 to 1840, the land-based Hudson’s Bay Company founded Fort Simpson and replaced the declining sea otter trade with an expanded market for marten, bear, otter and beaver. Native settlements soon began to spring up near these newly established trading areas, and a prolific period of totem-pole carving began along the Northwest Coast.

Excerpted from Totem Poles, by Pat Kramer, 1998, Heritage House Publishing.