What: Amadeus

Where: Phoenix Theatre

When: To March 21

Rating: 4 1/2 out of five

There’s a bumper crop of good theatre blossoming in Victoria right now, such as Blue Bridge Repertory Theatre’s Waiting for Godot and Langham Court’s The Mystery of Edwin Drood. The latest bloom is an impressive production of Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus, which just opened at the University of Victoria.

Many of us know Amadeus from the 1984 film adaptation, which starred Tom Hulce as a hyperkinetic (and ultimately annoying) Mozart. No doubt aware of the danger of competing with big-budget cinema, UVic’s theatre department has opted for an interpretation that makes no attempt to replicate the movie’s visual fireworks.

Indeed, the opposite is true. Allan Stichbury’s terrific set resembles a giant dungeon — a dark, forced-perspective vault that encourages us to consider the serious themes underneath the comedy. But don’t worry — it’s far from doom and gloom. The costumes are sumptuous, a feast for the eye. And the pathos is evenly leavened with humour and hijinx.

With astonishing impudence, Shaffer presents one of classical music’s towering geniuses, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, as a vulgar, adolescent imp. We first see him playing chase-me-Charlie with his fiancée, Constanze, making childish scatological jokes and blowing raspberries. Sporting loud red breeches and striped stockings, Mozart is annoying in the manner of a randy 13-year-old who has missed one too many doses of Ritalin.

No one is more disgusted than Antonio Salieri, the Italian court composer, who correctly deems Mozart an “obscene child.” Despite its title, the play is really about Salieri — who historically was a popular opera composer in 18th century Vienna. In Amadeus, he’s the only one who can fully comprehend Mozart’s artistic genius . . . and his own musical mediocrity. Instead of giving him pleasure, the new rival consumes Salieri with a jealously that descends into madness.

Angry with a God who chose a spoiled boy as a conduit for His most heavenly sounds, Salieri gives up any pretense of being a good man. Instead, he devotes his life to undermining Mozart, an excruciating act of sadism (perhaps this explains the torture-chamber set) that’s both horrific and fascinating.

Salieri is a gargantuan role — the character never leaves the stage. Jenson Kerr does a commendable job, on Thursday night playing the role with confidence and brio. Kerr, whose handsome voice projects well, succeeded in making Salieri a sympathetic (albeit despicable) character, something that’s essential to the play’s success.

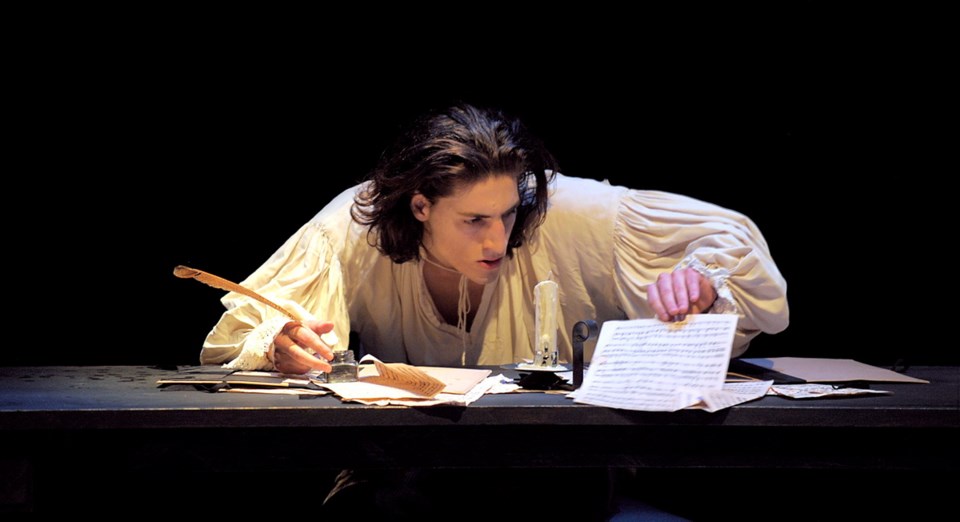

The other lead roles are also played by strong performers. Aidan Correia captures Mozart’s immaturity and eccentricity, his inappropriate laugh, love of silly jokes (sticking a wet finger into a courtier’s ear) and adolescent conceitedness. The physical vitality Correia displays on stage contrasts well with Kerr’s staid movements. Both actors have done fine work here.

Constanze, Mozart’s fiancée and then wife, is a more two-dimensional role. She’s almost a plot device, an intermediary between Mozart and Salieri. So it’s to Samantha Lynch’s credit that she skilfully brings out the life in this character; she finds Constanze’s pragmatic grit and ordinary-gal likability.

Director Chari Arespacochaga — who has imbued the show with wonderful vitality — has reset the opening and closing scenes of Amadeus in an insane asylum. The conceit is that Salieri, an elderly fellow who has lost his marbles, is narrating his life story from the loony bin. One can assume necessity was the mother of invention here, as this device eliminates the need to present myriad scenes (courts, opera houses, music halls, etc.). It’s an intelligent approach that works well.

The notion is further reflected in the superb costumes, designed by Pauline Stynes. For instance, the emperor (well played by Markus Spodzieja) wears aristocratic clothes, yet upon closer inspection, his breeches are tattered — the implication being he’s an asylum inmate transformed by Salieri’s fevered mind. The other members of the court are similarly attired.

The costumes are all rooted in the 18th century, yet the look is theatrically heightened. The singer Katherina wears a fantastical rainbow-hued dress that might have been borrowed from Cirque du Soleil.

Overall, this is an entertaining, satisfying production well worth seeking out.