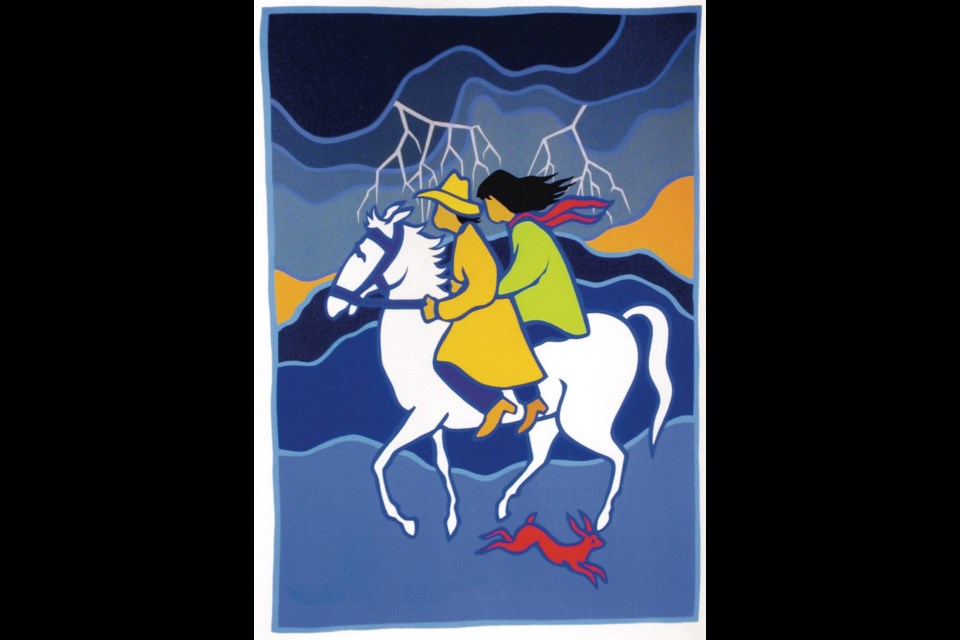

Ted Harrison is gone, but in his 88 years, he gave us much to remember. In hundreds of joyful paintings in his unique style, the uninflected colours he used seemed to shimmer and glow.

Ted Harrison is gone, but in his 88 years, he gave us much to remember. In hundreds of joyful paintings in his unique style, the uninflected colours he used seemed to shimmer and glow.

Rollicking curves define lakeshores and distant hills, swirling clouds and dancing Northern lights. These paintings don’t exactly look like the Yukon, but somehow they convey the essence of Canada’s North.

When he arrived in Carcross in the Yukon in 1968, Harrison brought a world of experience. From the slag heaps of Hartlepool, his hometown in the English midlands, he brought a classical art training. The discipline continued during his war years in the army, but the British greyness became infused with the colours of tropical climes where he was stationed.

He later taught elementary school with his wife Nicky and, in those classrooms in Malaysia and New Zealand, the reluctant scholars forced him to develop drop-dead comic timing. Harrison was the finest raconteur I ever met.

One day in the Yukon, a revelation changed this mediocre traditional painter into an inspired original. The first show of his new style, at the public library in Whitehorse, was fortuitously discovered by a visiting civil servant from Ottawa, who took the news back to our nation’s capital.

Harrison’s subsequent show in Ottawa in 1973 was a huge hit, and his “happy paintings” found a receptive audience among well-heeled civil servants. A followup show in Vancouver in 1974 sold well and he soon gave up teaching — an overnight success at 48 years of age.

Harrison’s unique style was adaptable. His illustrations for Children of the Yukon (1977) won him fame at the Frankfurt and Bologna Book Fairs. The Cremation of Sam McGee (1986) was named a Best Book by the New York Times. Hundreds of editions of handmade screen prints sold strongly; stained glass windows were commissioned for the Whitehorse cathedral; a giant walk-through Harrison painting was the Yukon pavilion at Expo 86 in Vancouver. Ted enjoyed the success and made himself available worldwide.

The Harrisons came to Victoria in 1993, in search of better health care for Nicky’s advancing Alzheimer’s disease. At first, they were lonely for the Yukon, but after Bob Wright of Oak Bay Marine Group introduced Ted to the whales and fishing off our west coast, he accepted Victoria as home. Harrison was active in the Rotary Club, volunteered for years as “artist in the school” at Monterey Elementary, and was always a feature of the Moss Street Paint-In.

Social service was natural to Harrison. During his first year in Canada’s north, in Wabasca, Alberta, he noticed his students were puzzled by the urbanism of their “Dick and Jane” readers. So he created A Northland Alphabet (1968), based on their tundra frame of reference. Nicky soon organized the other private kindergarten teachers and arranged for the Yukon school board to take responsibility for five-year-olds.

I got to know Ted later, at the annual Painters at Painter’s Lodge event at Campbell River. With his dog Maggie curled at his feet, wearing a Cowichan sweater and paint-spattered apron, he sat at his easel and told stories while he painted between the lines.

Amazingly, Harrison visualized his paintings entirely in his mind, while he lay in bed (he suffered from sleep apnea). So every line and colour was ready when he sat down to his canvas the next day. Though fans constantly interrupted him, Harrison painted on. In his latter days he made himself available in his studio in the front window of his shop on Oak Bay Avenue. His early discipline served him well.

Harrison was probably Canada’s most popular artist. Once I asked his business manager (for he truly needed one) if she was involved in promotion.

“Ted doesn’t need any promotion,” she laughed. “Every school child in this country knows him.”

They’ve all read his books, painted in his style and a surprising number of them have met him. It seems that this undeniable popularity made it hard for the high and mighty curators to accept him — our National Gallery doesn’t own any of his work … yet.

But that will surely change. His paintings are magic, even better “in the flesh” than in the cheerful reproductions or prints. And, with his prices going up and up in the auction houses, he must be accounted for. His work and his words are a hymn of praise for the country he came to love. Who else but Harrison could have successfully illustrated O Canada (1992), a book whose text is our national anthem?

Recently, I indexed the Ted Harrison papers, which were deposited in the University of Victoria’s Artists Archives. For months, I sorted through his correspondence, read his reviews, arranged his photographs and even laid out his paints, brushes and the paper plates he habitually used as palettes. I catalogued his editorial cartoons from the Whitehorse Star, his (as-yet unpublished) poetry singing praises of the Yukon and heaps of his correspondence, written in a neat italic hand, with more than 20 galleries that hosted his sell-out shows. The man was loved.

Harrison received honorary doctorates from four universities, was elected to membership in the Royal Canadian Academy of the Arts and was awarded the Order of British Columbia. Personally, my memories of him centre on his fund of naughty limericks and the irrepressible twinkle in his eye.

Ted Harrison is gone, but his was a life well-lived. We are all better for having known him.