During the past year, I have heard the name Sherry Tompalski in relation to a number of art activities. With her partner in life and art, Graham Thompson, Tompalski has painted video-enhanced portraits of refugees and female boxers training in Afghanistan. I recently visited the artists in their Oak Bay apartment.

During the past year, I have heard the name Sherry Tompalski in relation to a number of art activities. With her partner in life and art, Graham Thompson, Tompalski has painted video-enhanced portraits of refugees and female boxers training in Afghanistan. I recently visited the artists in their Oak Bay apartment.

Tompalski retired from her career as a psychiatrist, working for the Canadian Armed Forces and then the federal government. She and her husband moved to Victoria 18 months ago, from their home on 20 acres near Stittsville, outside Ottawa. But painting is by no means a hobby she picked up in retirement.

In fact, after high school in Saskatoon, she says she “horrified” her parents by enrolling in the art program at the University of Saskatchewan. Later, sound sense prevailed and she switched to medicine, graduating from the University of British Columbia. An internship led to a residency in Ottawa.

“It was really quite fantastic,” she told me. “There is a large psychiatric community, easily 300 psychiatrists, in Ottawa.” But when she finished her training in 1992, she couldn’t get a billing number in B.C. “So I stayed in Ottawa.”

In Ottawa, she started painting again.

“I got involved with a group of senior artists outside of Stittsville,” she explained. They shared 13,000 square feet, with large studios for all and two exhibition spaces. A huge benefit was the community of senior artists. The mentorship of Ken Finch led her to create big portraits with a strong narrative tendency.

As an outgrowth of life-drawing sessions, she began her Band-Aids series.

“Band-Aids hold you together while you heal,” she realized. “It was natural that I started painting about various psychiatric concepts.”

With the confidence that came from her full-time employment, she was able to ignore the art marketplace.

“I never really focused on whether it was commercial,” she told me. As it turned out, a great deal of the work was funded on grants.

That’s where Thompson came in. The two have been partners since undergraduate days. In the 1980s, with the emergence of the internet, he found work that led to desktop publishing, video, graphics, websites and then social media. His special skill was preparing video grant proposals.

Tompalski produced the content — the Wet Nurse series, the Reassembled Self series. And Thompson took the material to the world with a multi-tiered approach. His presentation of her paintings online with strong search optimization led to the publication of her images in a magazine in Brazil. Thompson’s video of her paintings in production was shown in film and video festivals as far away as Croatia.

His early videos resulted, to their surprise, in an invitation to present their work in the Philippines — all expenses paid.

“Things would start clicking,” Tompalski recalled, “and the more they clicked, the more they clicked. It worked really beautifully.”

Tompalski did not wait until she retired to take up art. At first she was well-supported by her friends in the psychiatric community, and submitted applications for every show going.

“Each time you write a grant,” she said, “it’s like having an art show. A jury of senior artists looks at your work. There is a lot of rejection, but they do look at it. And, before you know it, you start getting calls.” The Museum of Civilization in Ottawa heard about her and, out of the blue, asked to present her portraits of Pierre Elliott Trudeau.

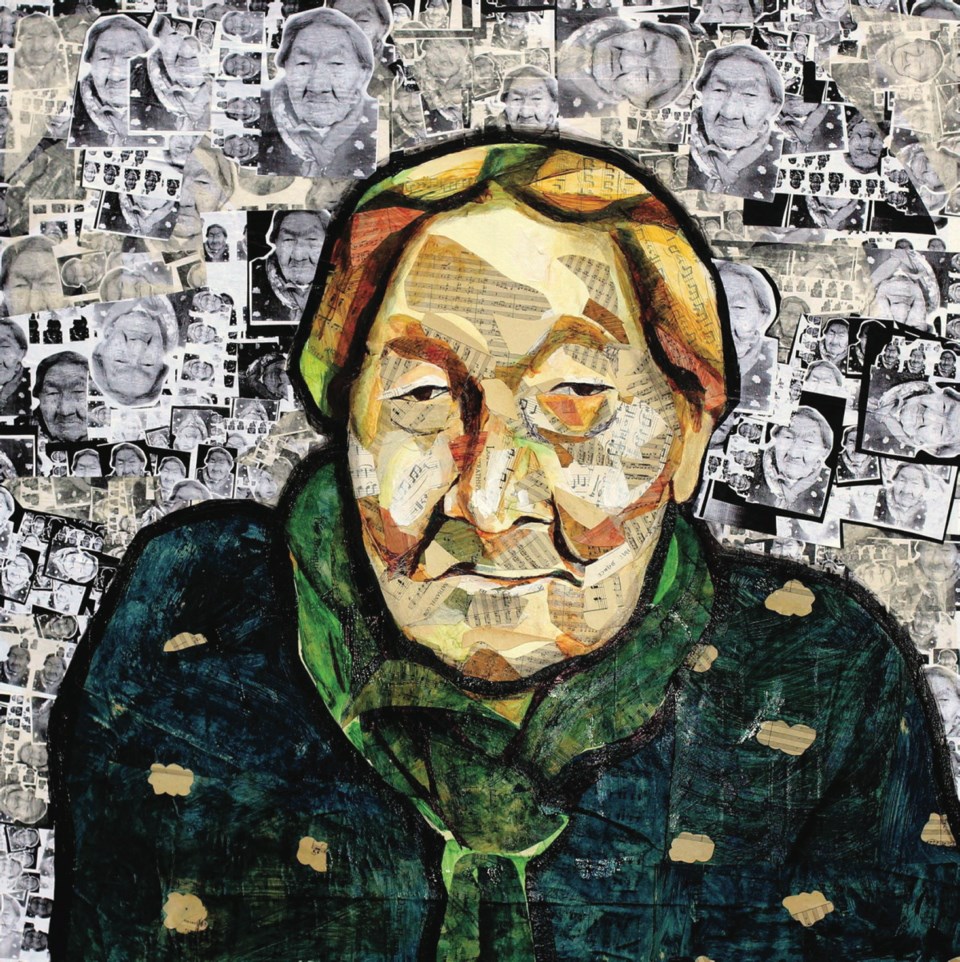

Her Refugees series is striking. Beginning with refugees from Afghanistan, the series eventually included people from many continents and backgrounds, including “internally displaced” First Nations and Métis people. And the series required much grant writing, as subjects were paid to sit for their portraits for three days. And later, there was translation to English and French.

In many cases, the artist did not understand what the model was saying, but, all unbidden, the sitters began to talk.

“They were trying to sit still,” Tompalski remembered. “It was meditative, with no one talking to them. And people would just start.” Thompson recorded the progress of the painting on video while Tompalski painted.

Regarding the video, “we would include a sample, just a minute or two, from three hours of tape, to enrich the portrait,” Tompalski said. “This was not an interview. They’d come in and just start talking non-stop, for three hours. Many of the sitters wanted people to know what they went through. For some, it was their first opportunity to really talk about what happened. They can’t talk about it with their families, who just want to put it behind them. And they can’t share it with other Canadians, who don’t really understand … and it’s just such a downer. So they’re just sort of left with it.”

The portrait sittings were the beginning of the processing of what happened to them. The subjects seem to be happier people just for the fact of having been heard.

“As a psychiatrist,” Tompalski reminded me, “I was trying to help people discover their own narrative and to figure out their own story. This started to manifest itself in the art.”

The artist had spent a summer here long ago. In retirement, she and Thompson have come back, and they are already part of the Victoria art scene. They are producing work for a show at the Gage Gallery (2031 Oak Bay Ave., Feb. 14 to 27). Featuring collages and paintings, costumes, online presence and performance, it’s entitled Sex and the Single Seagull. See you there.