Prescriptions of antipsychotics to youth for off-label uses in B.C. are soaring — most often for depression, even though there is no evidence to support their use for this disorder in children — according to a new study.

The population-based study looked at antipsychotics prescription trends in children and adolescents in B.C., from 1996 to 2011. It does not include prescriptions for youth in hospital.

“The high rate of [antipsychotics] for depressive disorders in our study requires further exploration given that there is no evidence to support the use of second-generation antipsychotics for depression in children and adolescents,” the study says.

Published Monday in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, the study is unique in that it shows who is prescribing the drugs, for what purpose and to which age groups, using information from B.C.’s PharmaNet database and the Medical Services Plan.

The study shows that it’s not just psychiatrists behind the “exponential rise” in prescriptions of antipsychotics for off-label diagnoses.

Family doctors and pediatricians who are also writing the prescriptions. One-third of third of antipsychotic prescriptions are written by general practitioners.

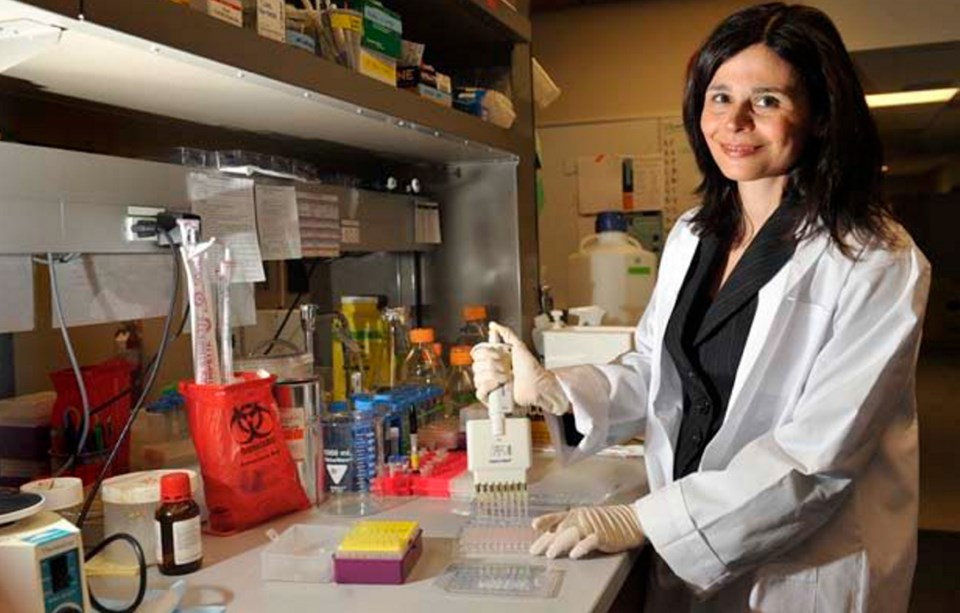

Constadina Panagiotopoulos, a pediatric endocrinologist at B.C. Children’s Hospital who co-authored the study, said the number of general practitioners prescribing antipsychotics to children for depression is a cause for concern.

“There is no data to support the use of second-generation antipsychotics in adolescent depression, so the fact depression was one of the top things is very concerning,” Panagiotopoulos said.

So-called first-generation antipsychotics (during the 1970s) and second-generation antipsychotics (1990s) were prescribed most commonly in the province for depressive disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and neurotic disorders, in that order.

Meanwhile, the labels recommend the use of these drugs in adults to manage psychoses — including delusions — particularly in people diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Only aripiprazole, or Abilify, is approved for use in teens 15-17 — and only for schizophrenia. “All other prescribing is off label,” Panagiotopoulos said.

As of 2010-11, B.C. general practitioners were prescribing antipsychotics most often for depression and anxiety. Pediatricians prescribed them most for behavioural and emotional-type disorders, as well as developmental delays. Psychiatrists prescribed antipsychotics most often for psychoses, anxiety states, depressive disorders and behavioural disorders.

“The exponential rise in off-label, second-generation antipsychotics prescriptions to children and adolescents is of clinical concern given the literature demonstrating that these medications can lead to serious metabolic side effects,” the study says.

Second-generation antipsychotics gained popularity mainly because they were thought to have better side effects.

Panagiotopoulos was in involved in research published in 2009 showing the metabolic side effects of second-generation antipsychotics: Children have more than double the risk of being overweight or obese and three times risk of developing diabetes.

Alan Cassels, a drug policy researcher at the University of Victoria and author of the book Seeking Sickness: Medical Screening and the Misguided Hunt for Disease, says antipsychotics play havoc with the body’s endocrine system.

Drug marketers “play down the metabolic stuff, but in the real world they are seeing the nasty effects of these drugs,” Cassels said. “And the probably more rare and serious effects are restlessness and ticks ... for some people it’s irreversible.”

The new study also shows the initial diagnoses were based on “the prescribing physicians’ judgment rather than by standardized research diagnostic techniques.”

“My concern is how are these drugs being marketed to the general practitioners and pediatricians,” Panagiotopoulos said. “Is it clear from the people marketing those drugs that the studies haven’t been done in adolescents and youth?”

The study recommends targeting all three physician groups to receive more information on evidence-based prescribing by age group and to better monitor antipsychotic treatments for side effects. That work is underway.

“In all these kids, are the medications the best choice here or could there have been other modalities for treatment that could have been used?” Panagiotopoulos asked.

She said the message is not that antipsychotics are bad. They can be life-saving in cases of severe aggression, true bipolar disorder and psychoses, and can help in dealing with severe autism, for example. But the drugs can come with serious side effects — significant weight gain, the increased production of cholesterol, hypertension and type 2 diabetes.

The study was conducted by: David Scott, former B.C. Health Ministry researcher; William Warburton, health and labour economist; Ramsay Hamdi, former B.C. Health Ministry senior economist; Rebecca Ronsley, University of Toronto medical student; Dianna Clare Louie, University of British Columbia resident in pediatrics; Jana Davidson, Children’s and Women’s Mental Health Centre of B.C. psychiatrist-in-chief; and Panagiotopoulos, also an associate professor at UBC.

The study showed an 18-fold increase of second-generation antipsychotics prescribed over 15 years ending in 2011. The total number of youth who received a second-generation antipsychotic prescription in 1996-7 was just 315. That jumped to 5,432 prescriptions in 2010-11.

Male teens ages 13-18 saw the highest increase of prescriptions of antipsychotics — a four-fold increase. For that age group, family doctors wrote more than 38 per cent of the prescriptions, psychiatrists wrote 39 per cent, 13 per cent were written by pediatricians and the remainder by other specialties.

“In our study males were significantly more likely to be prescribed an antipsychotic in an office visit than females,” the study says. This is consistent with other reports, the authors said.

A study from the United States showed a profound increase in prescriptions to older children was most commonly for schizophrenia and psychoses.

“In contrast, our data revealed a multitude of diagnoses for which antipsychotics are being prescribed,” the study says.

One possible theory for why depression is the most common diagnosis for the prescription of antipsychotics in children is that doctors are using the diagnostic code for depression when, in fact, other conditions are present.

For more information on second-generation antipsychotics and their side effects, see keltymentalhealth.ca