British Columbia’s Grade 12 History curriculum covers a lot of territory, much of it relevant to an understanding of today’s news: The perils of nationalism, authoritarian regimes, Indigenous peoples’ movements and migrations.

These topics are not only part of history, but are also topics du jour.

Much of the value of history is not the names, dates and places students are required to memorize, but the light it shines on the otherwise baffling politics of current events around the globe.

The challenge for teachers is that teaching anything that touches upon politics, in our system at least, can be professionally perilous.

Teaching history and its relationship to “the now” requires maintaining an impartial point of view and a deft hand on the whiteboard.

Reassuringly for B.C. history teachers, one of the expected outcomes for Grade 12 students is to learn how “to make reasoned ethical judgments about controversial actions in the past or present,” and assess whether there is a responsibility to respond, especially for those now moving toward eligibility to participate in the electoral process.

A potentially contentious topic that struggles more and more to the surface of media coverage of world events is Democracy and, as history relates, its rise, fall and fragility.

As a theme, most of the history of the western world’s great events have occurred in pursuit of Democracy. That’s capital “D” Democracy — undefined but nonetheless regarded as the sacrosanct objective of western governments.

As Harvard political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt explain in their scholarly analysis of the subject, How Democracies Die, Democracy means far more than simply majority rule: “It involves constraints and delays on majority rule, protection for minority rights, diffusion of power, free speech, free assembly and accountability for elected officials.”

Democracies, say the authors, can and do erode slowly in barely visible steps: “Damage to a Democracy extends beyond policy differences into an existential conflict over race and culture ... and it is clear from studying breakdowns throughout history, that extreme political polarization can kill Democracies.”

Levitsky and Zinblatt provide compelling examples, down through the centuries, of how elected demagogic leaders can gradually subvert the democratic process to increase their power.

Demagogues have always thrived in democracies and have always been able strike a note that resonates with a sector of the population to the extent that they gain power.

Julius Caesar was a charismatic and unconventional politician who knew what the masses wanted to hear. He used his immense wealth to fight his way to the highest ranks of political power.

He promised to shake things up and he did, but it wasn’t long before he proclaimed himself dictator for life.

Demagogues play to popular prejudices and misinformation. The greatest danger to Democracy, suggest Levitsky and Ziblatt, is a struggling population in search of easy answers.

More recently, Hitler, Mussolini, Franco, Batista and Somoza, Diaz, Pinochet and now Putin all deserve a mention, and a brief look at the role they played in the decline of democracy in their own nation states.

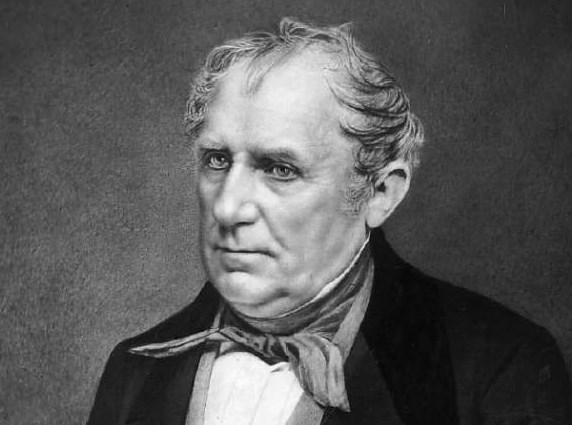

Back in 1838, author and sociopolitical commentator James Fenimore Cooper identified fundamental characteristics of demagogues: They fashion themselves as a member of the common people, opposed to the elites. Their politics depend on a visceral connection with “the people,” which greatly exceeds ordinary political popularity.

Demagogues, wrote Cooper, manipulate this “connection,” and the raging, almost mindless popularity it affords, for their own benefit and ambition.

Part of the demagogue’s attraction to those believing themselves disenfranchised by “the elite” is that he/she threatens or simply breaks established rules of conduct, institutions and even the law. Not surprisingly, history identifies that it is usually the narcissistically damaged actors who become political performers.

Other historians have identified four other behavioural warning signs of an emerging authoritarian demagogue: He/she

1. rejects, in words or action, the democratic rules of the game,

2. denies the legitimacy of opponents,

3. tolerates or encourages violence,

4. indicates a willingness to curtail the civil liberties of opponents, including the media.

In some democracies, political leaders heed these warning signs and, when faced with the rise of extremists or demagogues, make a concerted effort to isolate and defeat them.

In other circumstances, as Jonathan Rauch, a Brookings Institution senior fellow wrote in National Affairs (“Rethinking Polarization”), there is “a vast emptiness at the core of politics [that] eases the way for faith to be placed in the promises of the demagogue.”

That thought alone makes a study of Democracies and their rise and fall a significant topic at the Grade 12 level, especially for those whose future involves the responsibility of understanding what Democracy really means and voting for it.

Geoff Johnson is a former superintendent of schools.