There was a time, not so long ago, when a respectable high-school graduation opened doors to a career of some kind. That has all changed. In fact, a university degree or college qualifications no longer guarantee anything.

According to a recent CBC News report, recent university or college graduates are finding a post-secondary education is not an automatic promise of stable employment.

In the fall of 2018, there were 1.7 million students in Canada heading back to post-secondary schools. In a volatile economy and an era of technological change, these students will have to apply knowledge and skills to meet very specific and sometimes unanticipated employer needs in a changing world in order to succeed.

An undergraduate (bachelor’s degree) university education was always thought to be one of the best ways to adapt to a rapidly evolving global workforce and launch lifelong career success.

It is in that context that nowadays something like a post-graduate degree in, for example, business management, seems essential and on most most lists of post-grad career opportunities that level of qualification assumes something beyond a bachelor’s degree in finance.

Upon graduation, grads will be eligible to work in a variety of financial roles, such as security analyst, market-research analyst, bank manager, mortgage broker or portfolio manager.

After two years of post-grad foundational business courses, students who specialize in finance management will learn how to plan, manage and analyze the financial aspects of businesses, banks and other organizations.

The problem is that for many students (including me), advanced business-management degrees are more tied to math than commerce, which involves students learning about theories and models in statistics and programming, and how to apply them to a variety of business problems.

The average compensation for these jobs is quoted by Statistics Canada at about $110,000.

At the other end of the salary scale are careers in civil engineering ($80,000), nursing ($84,000) and careers in payroll and market-research kinds of situations.

Teaching doesn’t even rate a mention.

So, what is a soon-to-be high school grad to do?

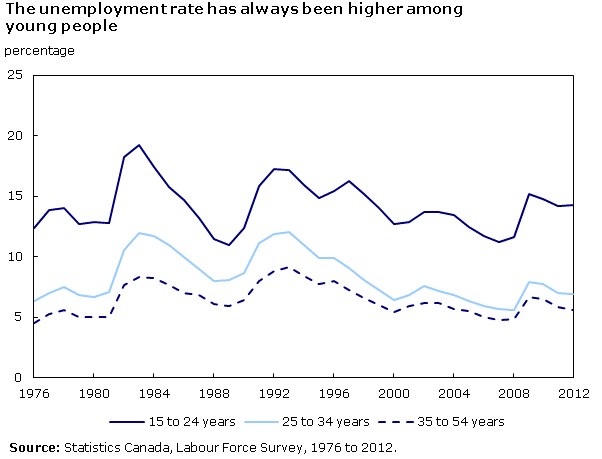

The bad news in all this is that more than 12 per cent of Canadians between the ages of 15 and 24 are unemployed and more than a quarter are underemployed, meaning that despite planning that results in undergrad degrees, kids end up in jobs that don’t require them.

Again, numbers from StatCan show the unemployment rate for 15-to-24-year-olds is almost twice that of the general population.

For them, being unemployed while having a degree is kind of a setback. They are now in debt, sometimes serious debt, but cannot find a job.

Sandro Perruzza, the chief executive officer at the Ontario Society of Professional Engineers, is familiar with the problem and advised applying for co-ops or apprenticeships while still involved with post-secondary classes.

The idea is to avoid what has become known as the “the millennial side hustle” (also known as the gig economy), meaning no steady job but also no safety net. Other economic indicators that track employment reveal a trend toward more precarious jobs, especially in the service industries.

The good news is that some institutions, such as the University of Regina, recognize the problem as one partly of their own making and, if they want to stay in business, need to come up with alternatives.

U of R’s Guarantee program, launched in 2009, turns the unwritten promise of post-secondary education into an actual guarantee. If a student enrolled in the program doesn’t get a full-time job in their field within six months of graduation, they can return for a year of undergraduate study tuition-free.

“The reason we do this is we know that if students do all the things that are part of the program, they are going to be successful,” said Naomi Deren, associate director of student success at the university.

Students from any department wishing to come back and maybe change career directions can enrol in the program and must complete career development training, including resumé reviews and job-interview seminars.

In their final year, students are required to network and complete a labour market overview in their chosen field. Their job search begins while they are still at school.

“The average student doesn’t … do that preparation, isn’t thinking about a career even by the end of second year and is sort of left scrambling at the end of it,” says Deren.

Of the 120 students who have participated in the program, only two have come back for the free year.

The further good news is that in the long run, people who graduate with a post-secondary degree or have completed post-secondary qualifications of any kind eventually will fare better in the workforce and, notwithstanding all of the above, are more likely to find a job than someone who only completed high school.

According to StatCan, they will earn considerably more as well.

Geoff Johnson is a former superintendent of schools.