It is 2020, and evidence of the applications of artificial intelligence is everywhere.

I turned on my email program this morning, and there was a message from Netflix reminding me that last night I had watched only half the movie. That, for me at least, is a scary proposition.

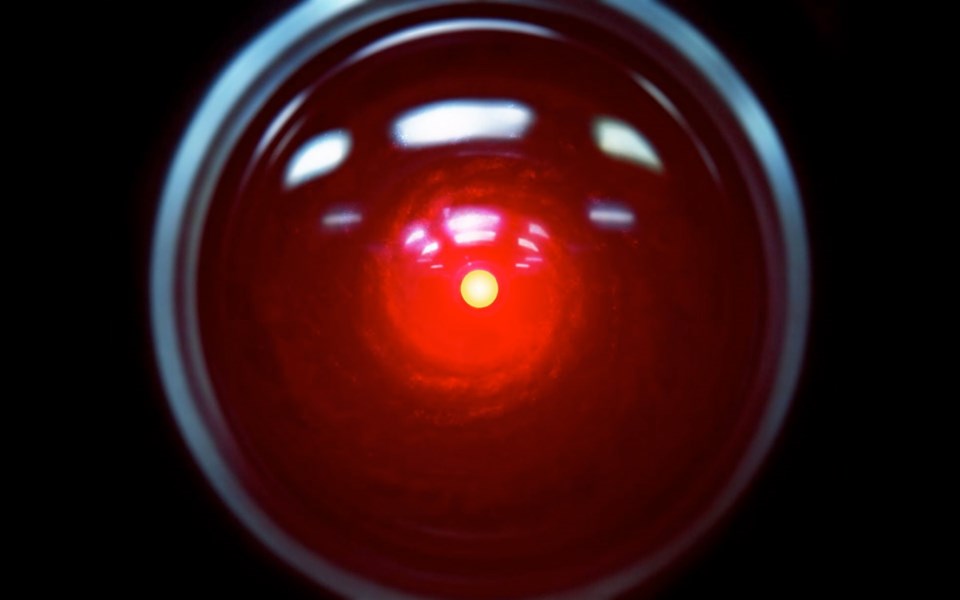

It reminds me that some kind of AI software, not a Netflix gnome, is monitoring my TV habits.

The only thing missing was an accompanying analysis of my social traits, motivations, personality strengths and weaknesses.

For all I know, Netflix could be already analyzing that information, because it persists in recommending other movies I “might enjoy.”

Although the term “artificial intelligence” was first tossed around as a field of study in 1956, it is only in the past 20 years with the everyday presence of gadgets such as Siri, Alexa, smartphones, streaming TV channels and plug-ins for AI-controlled houses that the term has achieved common usage.

The problem is that even the term “artificial Intelligence” implies that thinking can be reduced to a binary process. In fact, artificial intelligence is a great oxymoron because, while AI covers a multitude of technical applications, it is not actually “intelligent.”

As cognitive psychologist Howard Gardner explained in his book Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences, actual intelligence, human intelligence, is not just a series of on/off switches, but can be a combination of as many as eight or more different kinds of intelligence: Musical-rhythmic, visual-spatial, verbal-linguistic, logical-mathematical, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal and naturalistic.

In 2009, Gardner went further and suggested that existential and moral intelligences might also be added to the list.

Artificial intelligence simply refers to the ability of computers to mimic some human-like feats of cognition, including rote learning, logical problem-solving, basic yes/no decision-making, even simulated speech and language — all at the most rudimentary level.

The kind of artificial intelligence used in today’s everyday applications is considered “weak AI,” because it is generally designed to perform just one or two specific tasks more or less as well but sometimes faster than humans.

There are even limited applications of AI for teaching and learning.

It’s now possible for teachers to spend more time actually teaching and less time grading most kinds of multiple choice and fill-in-the-blank tests.

AI programs can do that instead.

While grading essays and poetry requires the higher-level thinking skills of critical analysis, and software for that is still in its infancy, it will probably improve over the coming years, although it might struggle comparing Shakespeare and E.E. Cummings side by side.

More interesting right now is the possibility that some AI-driven educational software can be tailored to fit individual student rates and styles of learning.

With teachers facilitating learning activities, using programs such as Khan Academy could supplement but not replace the work of human teachers, because AI cannot replace the intuitive relationship that exists between the best teaching and the needs of the individual learner.

Recently, while coaching a teacher trainee sitting beside me, I had the opportunity to observe an excellent math teacher in a Grade 11 classroom.

As the class worked independently, a student put up her hand and the teacher came to her desk. Her specific question was about a five-stage process to solve an algebraic problem.

“When you ask me a question like that, I know you are on the right track with this,” the teacher replied.

My teacher trainee was dismayed. “He did not answer her question,” he said.

I explained that the teacher had done a lot better than that. In commenting positively on the student’s progress, he had indicated that he had every confidence that the student could solve the problem given a little more time.

That teacher intuitively understood his student and her needs at that point in the lesson. It was not the answer she needed, it was a boost to her confidence.

AI can’t do that.

A teacher also understands that fluctuations in student performance, while measurable by an AI program, might well be due to factors and events outside the classroom; a family argument at the dinner table, the absence of any kind of breakfast before school, a playground confrontation that left the student nervous and unable to focus.

AI can’t “understand” students, but a human teacher can.

The best teachers see their individual students as whole, complex human beings.

In the same way that Netflix’s AI programs might have some insight into what kinds of movies I enjoy, at this point, thankfully, it does not know why.

As Paul Allen, co-founder of Microsoft put it: “There’s a long history of artificial intelligence programs that try to mimic what the brain is doing, but they’ve all fallen short.”

Hallelujah for that.

Geoff Johnson is a former superintendent of schools.