My father chose Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID). I was by his side through the process and supported his wish to end his life without prolonged pain and suffering.

But, in the end, our journey was complicated by the very system that sought to protect us — the system that determined exactly how, and when, my dad would give his final consent to die.

As I write, I can feel the tears and anguish rising as I am taken back to those days in hospital when my father was forced to set a date. It was a time fraught with both emotion and practical considerations, and I did not want to influence his very personal decision. But I did not want him to miss the opportunity to leave this Earth his way.

Assisted suicide, officially referred to in Canada as MAID, was what my father wanted. He was certain of his choice. But the issue we all faced was the issue of final consent, the very final request, when he was still medically competent to make that choice.

The rules are designed to protect the dying — one must give final, informed consent while completely lucid and aware, but also while very close to death, and these states are often mutually exclusive.

My dad very strongly wished for assistance in dying. He had watched my mother, the love of his life, die of cancer. Though it was decades ago, the experience stayed with him. When our 103-year-old grandmother was dying, my brother recalls that our dad made him promise that he would never allow a similar situation to happen to him. But for my dad, it was not a single diagnosis that would end his life, but rather an accumulation of illnesses, making timing impossible for anyone to easily estimate.

The day we first rushed my dad to the hospital emergency room, the doctors said he had several months to live. But after he was admitted, it became obvious to me that this may not be the case.

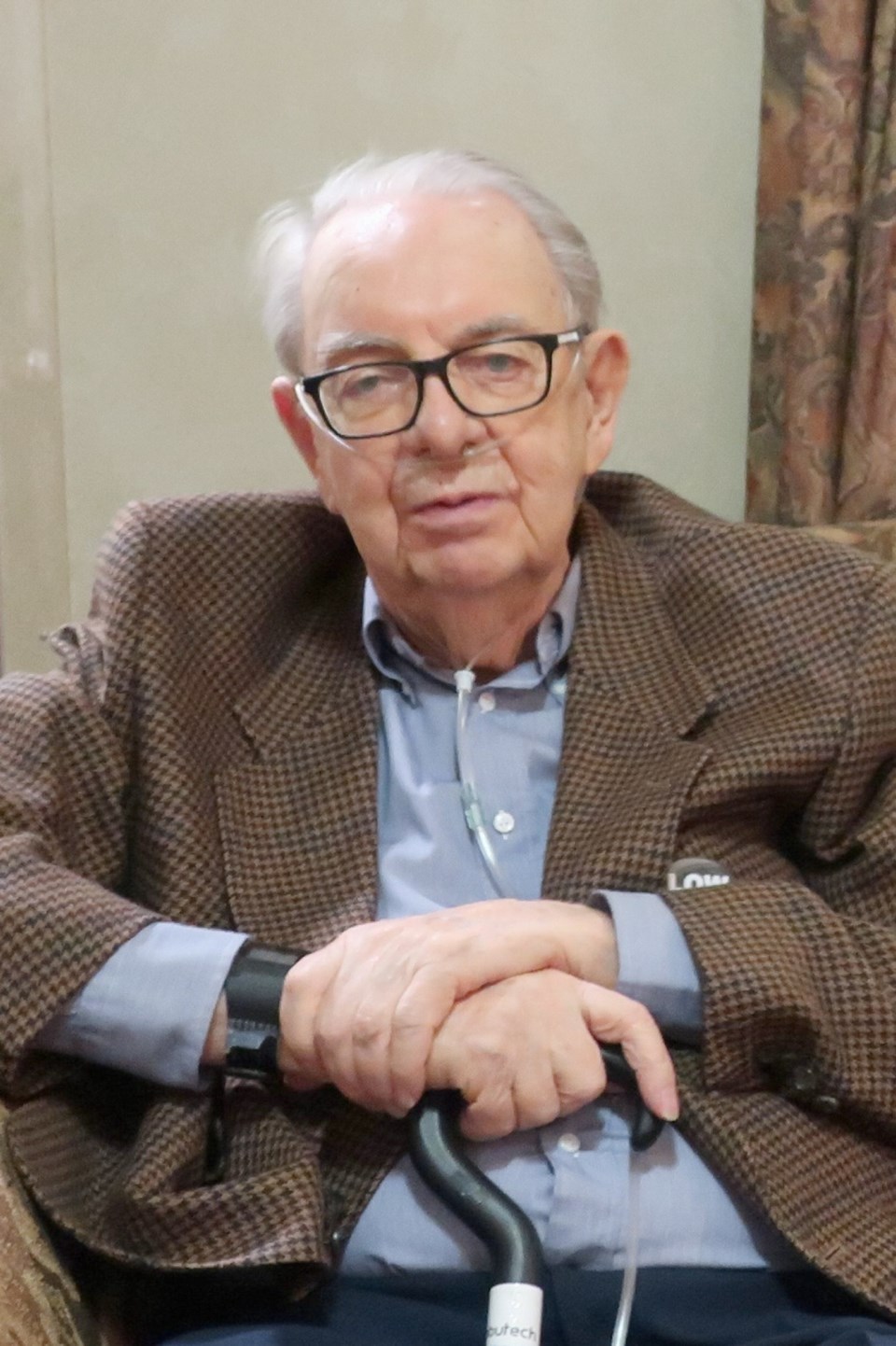

Still, it wasn’t as obvious to my father, a man with a stubborn streak, who had faced years of ongoing illness with incredible determination and stamina. He had endured pulmonary fibrosis, many heart and aorta rebuilds, and macular degeneration that left him legally blind.

His legs could no longer hold his dwindling weight, and now there was suspected stage-four lung cancer (which could not be formally diagnosed, as his lungs could not have withstood a biopsy).

His lungs and heart were petering out, leaving him bedridden.

But he was in good spirits and seemed at peace with knowing his life was coming to a close.

My father’s time in hospital was playing out like a movie in slow motion, yet the day-to-day changes in his health were coming at us too quickly. MAID allowed him to choose when and how his life would end, rather than await the inevitable, drugged and delusional in a hospital bed. And that is where things were headed.

And so the formal planning for MAID began in earnest. It was done with relative ease, thanks to the incredible team at Royal Jubilee Hospital. The doctors and nurses went over and over the plan, ensuring that he was certain about his wishes. The paperwork and corresponding interviews were difficult, but understandably so. It also gave my father and me the opportunity to ensure I was carrying out his wishes to the best of my ability and that I did so with clarity.

Though there is a 10-day waiting period from the time paperwork is signed to the date you can choose to die, we were comforted by knowing that this could be waived under certain circumstances. We were taking things day-by-day, sometimes hour-by-hour. No one was rushing his decision, but the fear of not being able to give final consent was hanging over it all.

Often of clear and sound mind throughout the day, my father sometimes became confused by evening. I experienced his downward spiral of irrational thoughts, in and out of sleep.

The nights were the hardest. I stayed to comfort him in these times, but I’m not sure I was doing a lot of good. I learned to go with it, crying silently in the dark, hoping that we hadn’t left his decision to set a date for MAID too late.

Dad might have hung on for weeks and weeks, but what kind of end would that have been for him or for his loved ones? Pain medication can help, but it often increases the confusion one experiences.

I worried constantly about what might happen. Would he be left in that bed — delusional, irrational and miserable — unable to give his final consent and hanging on for who knows how long? But does one really need to be rushed?

In the early mornings, often before it was light, Dad would awaken. From the couch beside his bed, I’d watch him stirring, eventually eyes wide open. He’d speak to me with clarity, ready for a new day. I’d finally exhale, relieved that we hadn’t left setting a date too long.

The doctors and nurses were also concerned that he might lose his opportunity for what he truly wanted if he waited much longer. With their gentle help, he finally set the date, just two days away. He requested a time later in the day but was discouraged, since he was always more aware in the earlier hours. They decided on 1:30 p.m.

Two days later, at 1 p.m., the house doctor arrived to get the final consent that was key to carrying out my father’s wishes — the final consent that I was so scared he wouldn’t be able to give if we waited much longer.

The doctor asked my father if he knew why he had come. My father simply said: “Yes.”

When the doctor asked for more detail, my father replied: “Let’s get this done.”

The doctor explained that my father needed to say what “this” was.

I don’t know what his exact reply was, because it stung. There was my father, so sure of himself — so sure of his fate. He gave his final consent as required. I could barely breathe in that moment. Twenty minutes later, I said goodbye to my father for the final time.

We are fortunate to live in a country where one can make the decision to end their terminal illness on their own terms.

I considered MAID a gift, as did he. But my father’s experience with MAID leads me to ask more questions about the process.

Why is Medical Assistance in Dying only available to those diagnosed with a terminal illness such as cancer and heart failure, and not to those whose illnesses will inevitably end in death — a long, slow, painful one? What about those people who are suffering from dementia or Alzheimer’s or multiple sclerosis, people who can’t give final consent at the end of life? Why is prior consent not enough?

Many may truly wish to end their lives and end their suffering, but they cannot give their consent as the law currently stands.

No one should find themselves in a situation where they have to make such a serious decision sooner than they really want to, because of a flawed system around final consent. But in your final days, you can’t always expect to be spry and thinking clearly. You’re dying!

My dad’s final wish was granted, but I have my own wish — that the government will change the process of consent around MAID, to ensure that others and their families have less to endure.

Canadians have the opportunity until Monday to voice concerns about MAID. Take the time to complete the online questionnaire to help ease the pain of dying. It’s our right. It’s our privilege.

> Online: justice.gc.ca/eng/cons/ad-am/index.html

Kathy McAree is a passionate advocate for dying with dignity. She is a professional marketer who loves all things culinary.