It was former Quebec premier Lucien Bouchard who coined the expression “winning conditions” after the 1995 referendum to describe what it would take for his Parti Québécois government to again test the will of Quebecers to leave the federation.

Bouchard never actually spelled out what the list entailed.

But control of both the national assembly and the provincial levers of power, along with a strong contingent of like-minded Bloc Québécois MPs on Parliament Hill and, from poll to poll, the steady support of more than 40 per cent of Quebecers for independence did not, in Bouchard’s book, add up to a strong enough pro-sovereigntist combination to chance another referendum.

By the time he retired from active politics in 2001, the man who had been sovereignty’s leading referendum champion no longer believed he or anyone of his generation was likely to see the day when Quebec became an independent country.

In the aftermath of last month’s federal election, talk of secession is more prevalent in the Prairies than in Quebec. But from the distance of the province that has been the ground zero of a significant sovereignty movement for half a century, that talk seems grounded in a very selective reading of current and recently past political realities.

Take “Wexit,” the word that has become popular to describe the movement to take Alberta and Saskatchewan out of the federation. A group purporting to become Alberta’s version of the Bloc Québécois seems intent on using it as its party label.

And yet the term draws its inspiration from a political mess that most serious secessionist movements have come to see as a deterrent to their own independence ambitions.

When a slim majority of voters opted to have the United Kingdom pull out of the European Union in 2016, there were those in the ranks of Quebec’s independence movement who saw Brexit as a development that would reflect well on their cause.

But three years later, few leading Quebec sovereigntists would be caught dead using the U.K.ís ongoing political adventure as proof of the feasibility of separation, let alone its economic benefits.

Watching Britain’s divided political class as it struggles to arrive at a consensus on a road map to an orderly exit from the EU, it is harder than ever to argue that there would be a smooth path to separation from the Canadian federation.

Closer to home, the Bloc is the other main source of inspiration for Wexit promoters and their Prairie supporters. But when it comes to leveraging gains for a region or a province, there is less than meets the eye to the usefulness of a permanent opposition berth.

On the week after the federal election, Premier François Legault took a pass on a meeting with Bloc Leader Yves-François Blanchet.

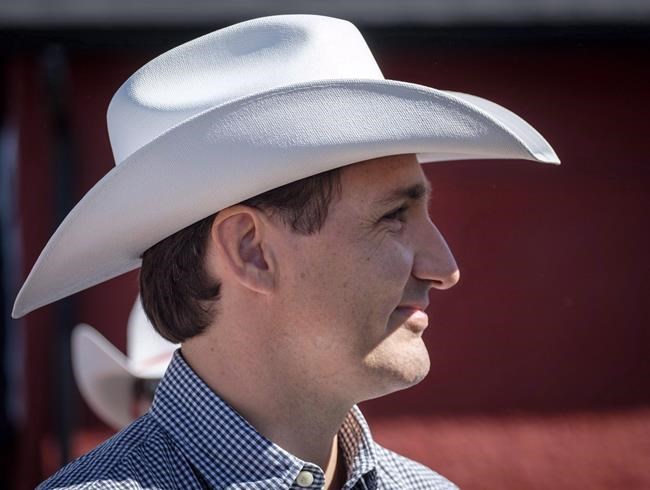

The premier wanted to make it clear he did not need a Bloc intermediary to deal with Justin Trudeau’s re-elected Liberals.

Going forward, Legault fully intends Quebec’s relationship with Ottawa to be based on direct, government-to-government dealings.

And while the Bloc will echo the province’s concerns in the House of Commons, its return to strength only makes it harder for a rival national party such as the Conservatives or the New Democrats to pry power out of the hands of Trudeau’s Liberals.

Looking at the Oct. 21 results, a successful Western-based separatist party would achieve gains almost exclusively at the expense of the federal Conservatives.

The latter, and not the Liberals or the New Democrats, would bleed support — and if not fatally, at least enough to be drained of the political energy required to come back to government. Voters in the Prairies would be trading a party vying to form a non-Liberal federal government for an opposition rump in the House of Commons.

The net result would be to increase the Liberal hold on federal power.

The Bloc would not have lifted off the ground as impressively as it did were it not for Lucien Bouchard’s charisma and popularity.

But even in the heady pre-referendum days, when support for secession was running at over 60 per cent in the polls, Bouchard kept insisting that the Bloc should not become a permanent fixture on Parliament Hill.

If Quebecers opted to remain in the federation in the referendum, he believed, they should not consign themselves to the opposition sidelines in the House of Commons.

Those words, of course, fell mostly on deaf ears.

Almost three decades on, the Bloc is still alive and kicking, but Bouchard has remained steadfast in his opinion.

Asked to comment on the resurgence of the party he founded, the former premier said he would rather have three ministers at the federal government’s table than 30 Bloc MPs.

Chantal Hébert is a political columnist with the Toronto Star.