Late on June 26, 2012, with just a few days left in the school year, the B.C. Teachers Federation reached a surprise deal with the government. It ended a year’s worth of labour headaches in schools.

Late on June 26, 2012, with just a few days left in the school year, the B.C. Teachers Federation reached a surprise deal with the government. It ended a year’s worth of labour headaches in schools.

There had been a three-day walkout, cancellation of some report cards and months of low-grade job action that frustrated many.

The deal was obviously portrayed as good news. It was presented as the result of a lot of hard work by negotiators and a special mediator (Charles Jago) trying to do the right thing.

But a B.C. Supreme Court judgment released Monday rewrites that story. It’s a tale of a government secretly wanting to provoke a strike that year for political reasons. There are always cynics who read political motives into big public labour disputes. But it’s startling to see a judge blame months of disruption in schools firmly on the crass political motivations of a government.

Justice Susan Griffin, who has been dealing with the differences between the government and the BCTF for a number of years, concluded “the government did not negotiate in good faith .... Government representatives were preoccupied by another strategy. Their strategy was to put such pressure on the union that it would provoke a strike .... The government representatives thought this would give government the opportunity to gain political support for imposing legislation on the union.”

The origins of this chapter of the 100 Year War that characterizes education bargaining in B.C. started in 2002, when the government introduced the Public Education Flexibility and Choice Act, which stripped the union of some bargaining rights. They did much the same thing with health workers the same day.

Health workers went all the way to the federal Supreme Court and won an overwhelming victory in 2007.

That case informed the B.C. Supreme Court decision (by Griffin) in 2011 that found Bill 28 unconstitutional and unfair.

She gave the government a year to fix the problem. It responded with the Education Improvement Act. The BCTF condemned that legislation and took it to court all over again.

That bill was part of the low-grade job action that filled the 2012 school year. And it’s the bill that Justice Griffin rejected Monday as an unconstitutional response to the earlier ruling that it had acted unconstitutionally in the first place.

Essentially, it did much of what the first bill did all over again, under the guise that it was OK this time because there’d been some consultation.

Griffin ruled: “From the start ... the government had a strategy in mind that it would be to its benefit if negotiations failed and if collective bargaining resulted in a strike and impasse.”

She said the government saw that a failure of negotiations “could be a useful political opportunity.”

She said the employer’s negotiator — Paul Straszak — co-ordinated and executed the strategy, partly by wasting four months of time and taking “manifestly unreasonable” stands.

“When a full strike did not materialize, so important was a strike to the government strategy that in September 2011, Mr. Straszak planned a government strategy of increasing the pressure on the union so as to provoke a strike.”

That included cancelling leaves and professional days, and trying — unsuccessfully — to cut their pay.

It didn’t work. The BCTF never declared a full strike.

Straszak was later promoted to head public-sector negotiations, then left government to work for the deep-pocketed B.C. Medical Association.

The other key player on the government side did all right, too.

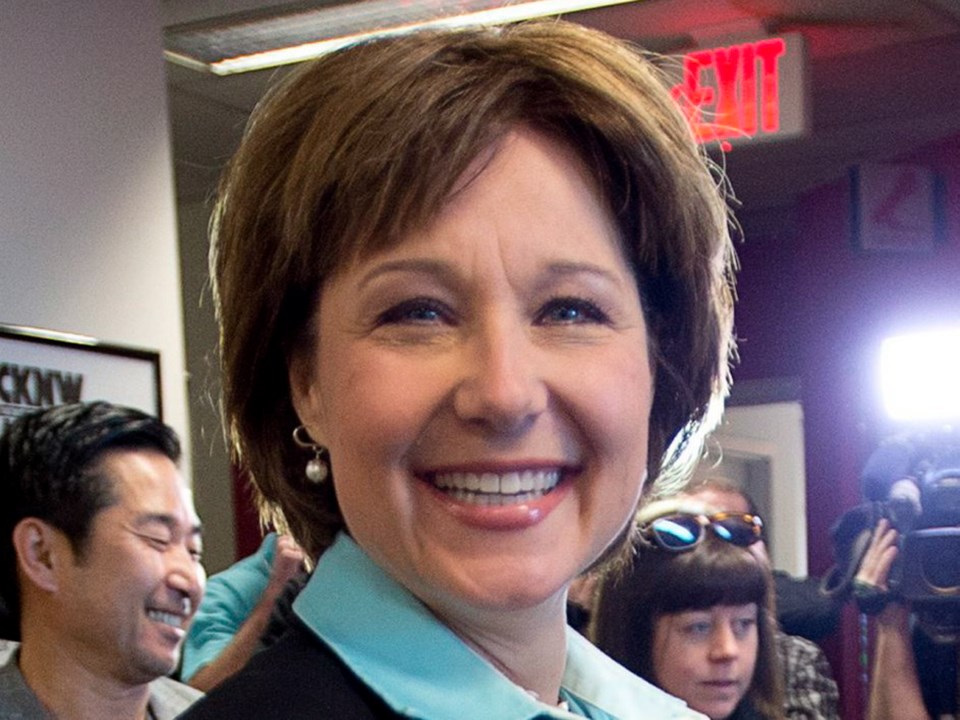

That would be Christy Clark, who was the education minister when Bill 28 was introduced in 2002. She stood up then and said it would help guide how children learn best, as opposed to being forced to decide by mathematical formulas set out in contracts done “by people we don’t even know.”

Ten years later, she was the premier of a government that, according to the B.C. Supreme Court, ran a lengthy con on parents and children to engineer some dim political advantage out of the argument created by the first bill.

Families first, indeed.