Three decades have passed since 18-year-old Tanya Van Cuylenborg and her 20-year-old boyfriend, Jay Cook, were slain in Washington state. They were on a trip from their home in Saanich.

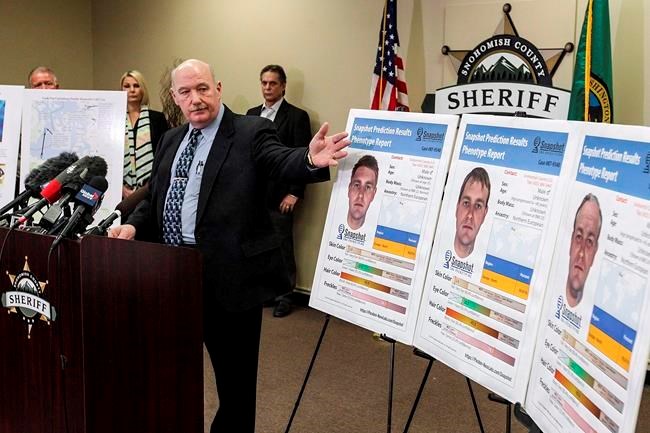

But now, as the result of a novel form of investigation, law-enforcement authorities in Snohomish County, Washington, have made an arrest. A 55-year-old American, William Earl Talbott II, has been charged with two counts of first-degree murder in the case.

It’s a welcome break in the case, but it raises legal and moral questions that society must answer.

DNA was recovered at the scene of Van Cuylenborg’s killing, using a rape kit. But without some idea of who the offender might be, that evidence was useless. And so it remained for 30 years.

But the rise of online genealogy sites gave local authorities a new search tool. The suspect’s DNA was compared with every sample held by one of these sites, and two matches were found. They turned out to be second cousins of Talbott.

Using this hint, police followed Talbott and recovered a sample of his DNA from a discarded coffee cup. It matched the DNA in the rape kit. Talbott is now in jail awaiting trial, and he is innocent unless proven guilty.

This isn’t the first such instance. A California man, accused of being the Golden State killer, was arrested this year using the same technology. A retired police officer, he had allegedly killed at least 11 victims.

But the procedure is contentious on several grounds. First, there is the question of legality. Do police have the right to troll through such sites?

The answer in the U.S. is yes, as long as the site is open, meaning anyone can access it.

In Canada, the situation is less clear. At a minimum, two conditions must be met. As with the U.S., the site must be open. But under our Charter of Rights, there is an additional consideration.

Constitutionally, each of us has a right to privacy. On that basis, the federal Justice Department has said that with the exception of a threat involving imminent bodily harm or death, any such search would require judicial approval. On those grounds, the RCMP do not search genealogy databases.

While understandable perhaps, this decision is open to dispute. In previous cases, the Supreme Court has ruled that each of the Charter rights, privacy included, is subject to such limitations as can reasonably be justified in a free society.

Some eminent legal scholars have concluded that DNA trolling meets the test of reasonableness, if no other practical options are available to solve a major crime. Do we really want to abandon such a powerful new technology?

It’s possible numerous unsolved murder cases might benefit from this form of investigation. A decade has passed since 24-year-old real estate agent Lindsay Buziak was killed while showing a home in Saanich. Police have reported no real progress.

We don’t know whether unidentified DNA was left at the site, and, understandably, Saanich police will not comment on their methods of investigation. But might searching genealogy sites provide a clue?

The second question concerns reliability. There are two issues here. The first has to do with the probability that a relative of the suspect will share enough DNA for a connection to be detected. This is essentially a practical matter when conducting a police investigation.

The odds must be manageable, and there are differing opinions about how far down the family tree matches can be found.

However, some experts give the following probabilities: For first and second cousins, there is a 99 per cent probability that a match can be made. For third cousins 98 per cent, and from there downward to 0.002 per cent for 10th cousins.

The second question about reliability is more important. Suppose a family match is found that leads police to a suspect, as happened with Talbott. How reliable is the comparison between DNA collected from the suspect and DNA left at the crime scene?

In a rape case currently before the B.C. Supreme Court, the odds of the suspect’s DNA being wrongly matched were said to be one in 1.1 trillion. That sounds pretty convincing.

But numerous errors can arise. Cross-contamination caused by mishandling the evidence can occur. DNA erodes over time.

And sloppy lab work is an issue. If the technician who reported those one in 1.1 trillion odds had a 20 per cent error rate, the chance of being wrong is far higher.

Lastly, there is the privacy issue. It’s unlikely that clients who sign up with a genealogy site expect police to look at their DNA.

And indeed in both the U.S. and Canada, if a site explicitly assures clients their data will not be shared, that’s pretty much the end of the matter. It would take exceptional circumstances for police to get a search warrant.

But what if the site is open? It comes down to a balance of needs: The need for personal privacy versus the need of law-enforcement agencies to find violent criminals.

This new technology offers, potentially, a huge opportunity to bring justice to the families of countless victims. However, a public debate is required, if only to give our police forces greater clarity. Perhaps the arrest of Talbott will prompt such a debate.