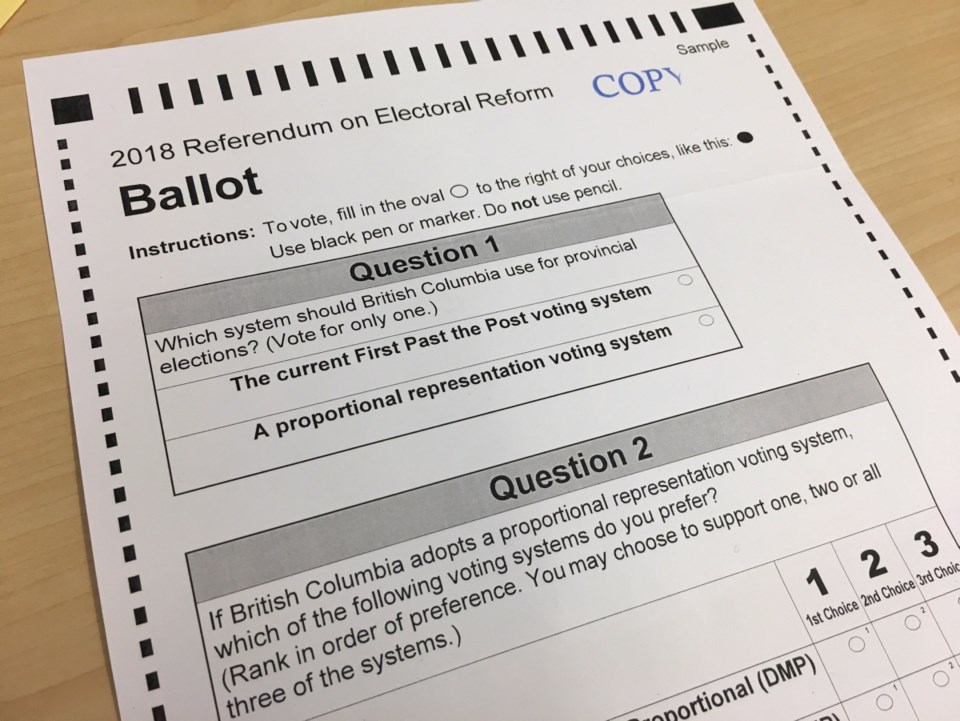

For the third time since 2005, British Columbians will vote on whether to change the way we elect our governments.

In normal circumstances, the Times Colonist does not support candidates or parties in elections. But on this occasion, we will take a position: B.C. should reject proportional representation.

Our present system has its faults, and proponents of change have raised important issues. It can be frustrating to see a party form a government with less than 50 per cent of the vote.

But the question before us is how we wish governments to be formed and administered. At present, political platforms are laid out in the weeks preceding election day. That means voters can make a reasonably informed choice.

By and large, we get what we vote for, and if we don’t, we elect someone else next time around.

But with proportional representation, that assurance ends. The problem is that PR leads to endless and ever-changing coalitions.

Under PR, policy is hammered out after the election is over, not before it. Backroom deals and bargaining sessions determine the path forward, in some cases dictated by fringe parties who would never be elected to govern. This is not democracy.

It is understandable that people want every vote to have statistical equality. Proportional representation promises that.

But elections are about more than expressing a preference, with every ballot counting the same. They are also about forming a government, and ideally a government that is stable, middle of the road and ultimately accountable.

In a coalition of four or five parties, who do we hold responsible if promises are broken?

There are also serious procedural concerns. The minister in charge, Attorney General David Eby, has admitted that there are least two dozen unanswered questions about how any new system would work.

This is not just asking us to buy a pig in a poke. It is asking us to buy a poke with little idea what might be inside.

We don’t know what the newly formed electoral districts would look like if the referendum succeeds. We don’t know how many people each MLA would represent. That raises questions about the ability of voters to know and trust their elected representatives.

Then again, the government has declared that a yes vote of only 50 per cent plus one will suffice. But there are serious constitutional issues here.

When the question of Quebec seceding arose, the government of that province claimed 50 per cent plus one would be sufficient. The Supreme Court of Canada disagreed.

The court did not impose a precise requirement, but it made clear that any yes vote would have to represent a substantial majority of voters. There will be court challenges if a referendum of such fundamental importance passes with a paper-thin majority.

Lastly, no provision has been made to protect the interests of lightly populated regions, some on Vancouver Island, many in the Interior. Essentially, residents of the Lower Mainland will likely determine the outcome of the referendum, regardless of what voters elsewhere might think.

But this is contrary to one of the indispensable features of any democratic system. It is well understood that the needs of large urban centres can differ significantly from more remote areas.

Currently, we protect that principle by including fewer residents in rural electoral districts than in urban centres. Thus during the 2017 provincial election, about 10,000 votes were cast in the Nechako Lakes riding. In Vancouver-Fairview, nearly 30,000 votes were recorded.

Does that make rural votes worth more than urban votes? Individually, yes. Collectively, no. That is how we preserve the urban/rural balance. If this referendum passes, that balance will be destroyed.

Premier John Horgan argued, in the referendum debate last week, that our current system dates back more than a century, and something more “hip” is required.

Yet Canada is consistently acclaimed one of the most attractive countries on the planet. Why change the very system that made us so attractive?

We need to be clear about the choices at stake here — stable and accountable government, or government by backroom deal-making.

To us, the answer is clear. Proportional representation deserves to be defeated.