This is the fifth in a series of columns about the First World War, leading up to the 100th anniversary of the armistice on Nov. 11. Today’s piece examines the after-effects of the hostilities, some of which continue to this day.

Seen at the outset, the Great War appeared no different than countless conflicts that had gone before. It was a war to shore up an empire (the Austro-Hungarian); it was a war to seize territory; it was a war to settle long-standing animosities between neighbouring countries.

That it was marked by staggering loss of life was certainly new. But the animating forces were as old as human civilization.

However, as the conflict ground to a halt, an entirely novel phenomenon stood waiting in the wings — the rise of aggressive, ruthless ideologies.

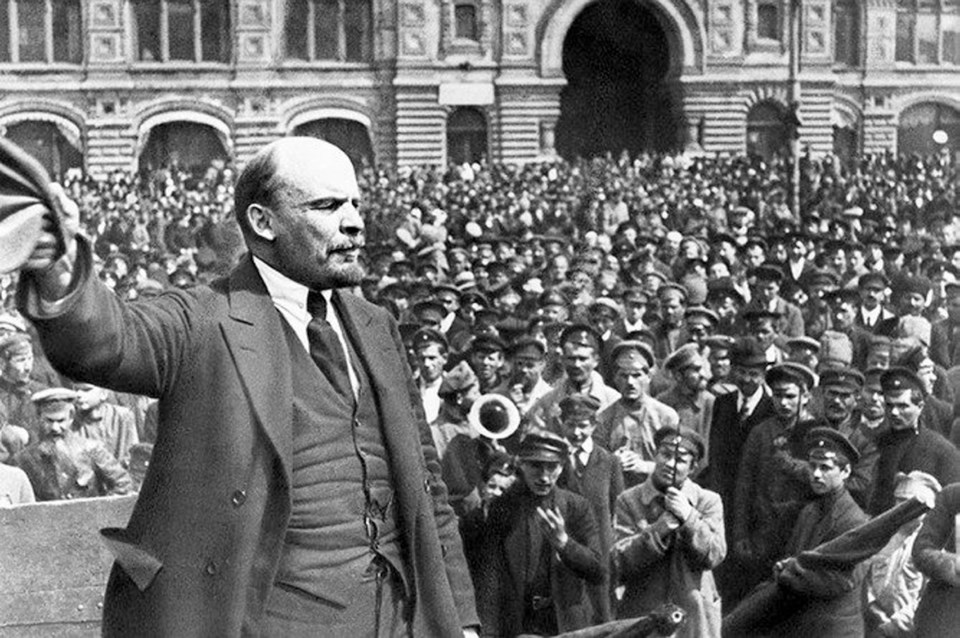

First to come was communism, as Vladimir Lenin seized power in Russia. Never a man to let a crisis go to waste, he saw in the exhaustion of the Czarist regime an opportunity to force an alien ideology on a country of peasants.

So unpopular was the enslaving of an entire population that his successor, Joseph Stalin, starved or outright murdered an estimated 20 million of his countrymen to maintain his hold on power. In China, 45 million civilians lost their lives as Mao Zedong imposed his own version of Marxism (though he spared the prettiest young women to act as his courtesans).

Now, you could say, wait a minute, what about all those wars between Protestant and Catholic states in the Middle Ages. Weren’t those wars of ideology?

But there is an important distinction. Nothing in New Testament liturgy contemplates, far less validates, the murder of non-believers or the use of violence to expand borders. (The Old Testament is another matter, but it long ago ceased to be a motivating cause of war, if ever it was.)

Those values are inherent in communism. It is to be spread by whatever means are necessary. Hence the imprisonment of central Europe after the Second World War.

Hence, also, the bloody effort to unify the Korean Peninsula under a Marxist regime. Ditto Vietnam and the killing fields of Cambodia. Thus also the seizure of Cuba and countless uprisings in African states.

Then came fascism, first in Italy, and later with appalling consequences in Germany. Here, too, the very nature of this ideology legitimized, indeed demanded, ruthless and exterminating policies.

And it is here that the after-effects of the First World War proved most destructive. It became thinkable, after the slaughter of that conflict, to impose monstrous ideologies that had never previously been contemplated, and which would have been rejected had anyone tried.

The stakes these ideologies played for were so high, they not only entailed the death of scores of millions, but today they threaten the planet.

True, fascism as a political reality subsided, as Italy and Germany were crushed. Communism, of course, lives on.

But here is the point. The issue is not the specific form these new ideologies take, or how many countries wield them at a given point in time.

The issue is that we have become acclimatized to living with threats that far exceed anything in our history. The price somebody, somewhere, is willing to pay to advance a perverted dogma has gone up exponentially.

And, of course, we now have the weapons to pursue such goals, though it’s unlikely anyone would survive to brag about it.

This, then, was the true cost of the First World War. It so deadened our senses that even humanity’s most basic instinct — the instinct for self preservation — can no longer be counted on to act as a restraint.

It almost came to that during those 13 fearful days in October 1962, when the Cuban missile crisis peaked.

That we walked up to the brink of annihilation and lived to tell the tale says nothing about the future. The forces let loose by the Great War still endure.