This is the fourth in a series of columns about the First World War, leading up to the 100th anniversary of the armistice on Nov. 11. Today’s piece focuses on the Versailles Treaty, which ended the war, but on terms that ultimately proved calamitous.

The British economist John Maynard Keynes, who attended the peace talks after the First World War, offered this appraisal: “Moved by insane delusion and reckless self-regard, the German people overturned the foundations on which we all lived and built. But the spokesmen of the French and British peoples have run the risk of completing the ruin.”

That France and Britain did exact a ruinous price is beyond dispute. Germany was required to pay reparations on a fabulous scale, reparations no defeated country could ever have paid after four years of unprecedented carnage.

Specifically, restitution was set at a massive $33 billion US. Although only $5 billion was ever paid, the settlement triggered a tidal wave of hyperinflation in Germany. By November 1923, the Deutschmark had collapsed from nine per U.S. dollar, to 4.2 trillion.

Making matters worse, while the allies slowly backed away from the original terms, their citizens continued to clamour loudly that Germany be squeezed “till the pips squeak.” This ensured that no gratitude or even recognition of the easing would be forthcoming.

The smouldering resentment engendered by the treaty played a leading part in the coming of the Second World War.

The question, then, is not whether Versailles was a disaster. The question is why the allies imposed such hate-inducing demands.

Previous conflicts had usually been settled for the losing country on manageable terms. Julius Caesar was a master at defeating his opponents, then offering a generous resolution. (Although Vercingetorix, leader of the Gallic tribes, might have differed with that assessment. He was dragged to Rome behind an ox cart and strangled in the public square.)

But no war in centuries had imposed such massive economic damage and such dreadful loss of life. It was inevitable that the victors would demand restitution on a commensurate scale.

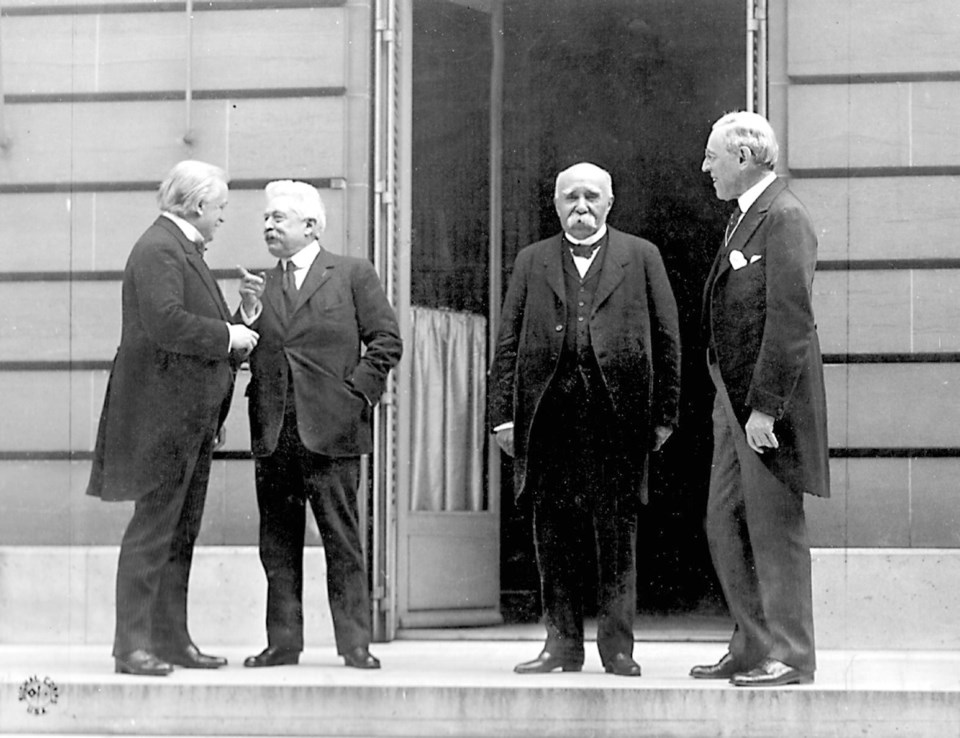

Although Britain’s prime minister, David Lloyd George, and his French counterpart Georges Clemençeau drove most of the negotiations, a moment is needed to dispose of U.S. president Woodrow Wilson’s contribution.

Wilson was an idealist with delusions of grandeur. He arrived at the conference with his “Fourteen Points” for achieving lasting peace (critics noted that even God had needed only 10).

Lloyd George said afterward that he had not done badly, “considering I was seated between Jesus Christ and Napoleon” (meaning Clemençeau).

But among the allies, Wilson had next to no skin in the game. France had suffered 1.4 million military deaths. A quarter of the country’s male population between the age of 17 and 27 lay dead. So, too, nearly a million British combatants.

Even Canada, with its small population, lost 65,000 killed in action — the highest casualty rate of all the combatants. But U.S. casualties numbered just 117,000.

Wilson’s role was, therefore, largely ceremonial. The big dogs were Clemençeau and Lloyd George.

And that is where the trouble began. Half the French countryside had been torn up, littered with barbed wire, pockmarked with shell holes and criss-crossed with entrenchments. Mines had been flooded, factories destroyed, farms wiped off the face of the Earth.

Worse still, this was the second time in two generations that Germany had attacked France (in 1870, Prussian troops defeated their neighbour and seized the French province of Alsace-Lorraine).

Clemençeau was in no mind to be generous, or even reasonable. He wanted Germany reduced to a non-industrial state, and set about trying to achieve it.

Lloyd George had slightly more negotiating room, though his countrymen were yelling for the Kaiser’s head. Yet the country was brought close to bankruptcy in paying for the war. The decline of Britain as a world power began around this time.

Thus, although the British PM was able to talk Clemençeau out of his more bloodthirsty schemes, in essence both leaders faced the same reality. Each man had behind him an enraged population that would not, could not, see sense. Any serious efforts at mitigation would have led to the instant downfall of both the French and British governments.

This is the real toll inflicted by the First World War. It brought such unthinkable horrors that even thoughtful people lost their moorings.

Next week’s column attempts a broader reckoning of the weregild (in ancient German, the cost of an offence) imposed on humankind by the Great War.