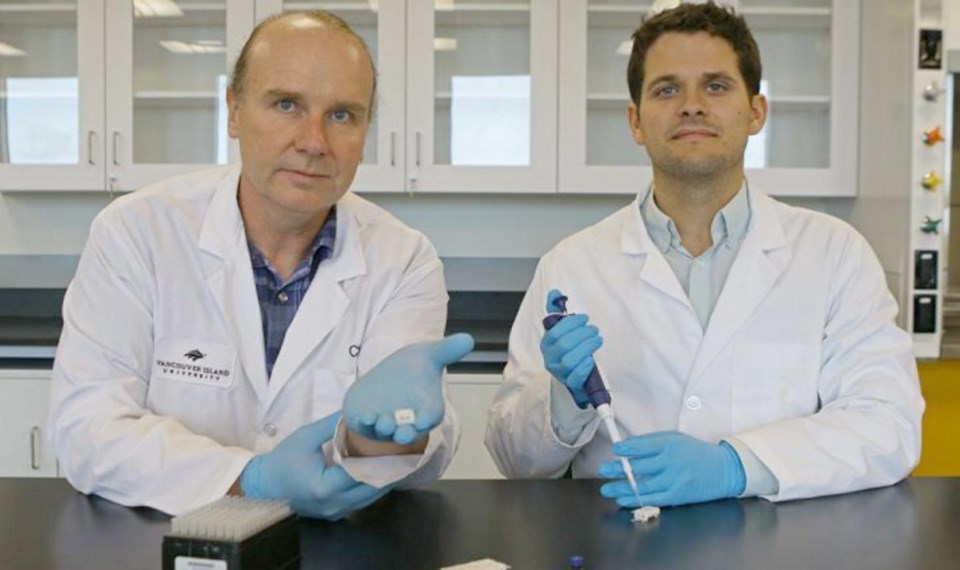

A team of researchers from Vancouver Island University have made a breakthrough that could save lives amid B.C.’s opioid epidemic.

Led by chemistry professor Chris Gill, researchers have developed a drug-testing method that, within minutes, could tell an opioid user whether the drugs they’re about to take contain a lethal dose of fentanyl. A sample of the drug is analyzed using a paper spray mass spectrometer, which breaks down the molecules to identify which toxic substances are in the drug and how much, down to a tiny fraction of a percent.

“We can tell not only what’s there in a contaminated drug sample, but how much is there,” said Gill, co-director of VIU’s applied environmental research laboratories. “And in harm reduction, it’s important to let the patient know what’s present in their drugs sample to hopefully modify behaviour in the hope of preventing deaths and overdoses.”

Carfentanil is so potent, one crystal is enough to cause an overdose, Gill said.

“So trace detection is key.”

The rapid drug testing strips currently used at some downtown Victoria pharmacies only give a positive or negative reading for the presence of fentanyl or carfentanil, which might not be enough to deter someone from consuming the drugs, Gill said.

Mass spectrometer technology is already being used to detect chemicals in other substances, for example in environmental testing, but Gill’s team partnered with Island Health, LifeLabs and consulted with the B.C. Centre on Substance Use to apply the method to harm-reduction drug testing.

About 85 per cent substances out there which are sold as heroin or opioids have fentanyl in it, said Dr. Paul Hasselback, medical health officer with Island Health.

Giving substance users more information could prevent them from taking heroin that could kill them, Hasselback said.

“The fact that we have this cutting edge research happening here on the Island is phenomenal,” Hasselback said.

Gill wants to see the development of a compact mass spectrometer the size of a small microwave, that could be used in overdose prevention sites, in community health centres and by mobile harm reduction teams across the country. The machine, Gill said, could be easily used by community health nurses and harm reduction specialists who are already connected to people using drugs.

“Providing them with accurate information about the cocktail of toxic drugs in a sample they're testing, they will be armed with the knowledge of what would be considered a dangerous or lethal amount of fentanyl,” he said.

To mass produce this technology, the team needs money and Gill has put in funding requests for several federal research grants.

He estimates one mass spectrometer would cost about $300,000, but Gill said you can’t put a price on the number of lives that could be saved, the number of overdoses prevented.

Fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid at least 50 times more potent than heroin, has been the primary factor in the spike of fatal overdoses since 2012, according to the B.C. Coroners Service.

The drug was detected in 84 per cent of illicit drug overdose deaths in 2017 and 81 per cent of deaths to the end of June this year.

B.C. is the epicentre of a public health crisis that has spread across the country, Gill said.

“I want to help B.C. lead the way in terms of what we can do to help in the opioid crisis.”