Work with ground-penetrating radar is expected to resume shortly on land around the former Kuper Island residential school, after being put on hold for more than a year because of the pandemic.

In recent days, the Penelakut Tribe revealed that more than 160 unmarked and undocumented gravesites have been found on Penelakut Island, previously known as Kuper Island. It’s just the latest revelation of suspected gravesites around now-closed residential schools in Canada, after the Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc First Nation used ground-penetrating radar to locate what it estimates as 215 unmarked graves at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School.

Work with ground-penetrating radar began on Penelakut Island in 2014, said Eric Simons, a PhD student in anthropology at the University of British Columbia who joined the effort a few years ago, working with the Penelakut Tribe’s chief and council and elders. Simons is part of a team that includes his UBC supervisor Andrew Martindale, who was involved with the earlier radar work

The ground-penetrating radar device looks something like a mower.

It was designed to identify large objects and changes in the ground below. Data collected must be carefully analyzed and interpreted on a computer.

Simons said the work is based on personal relationships and trust-building, with the First Nation determining where and when it wishes to see the radar used and the researchers following cultural protocols.

It can also be emotionally difficult, he said — abuse at many residential schools has been well-documented.

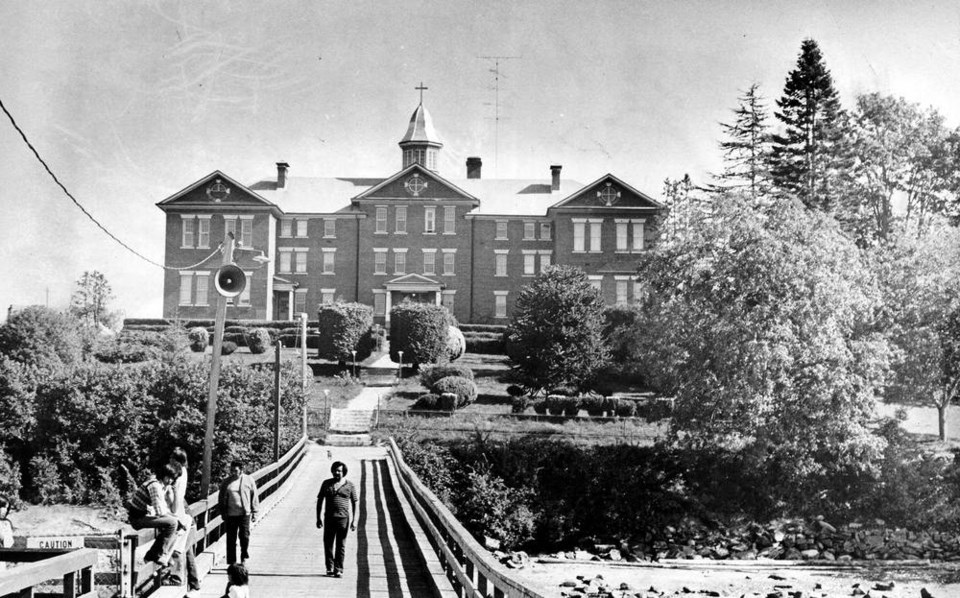

About 120 students are listed as having died at Kuper Island school, which opened in 1890 and closed in 1975.

The school was demolished in the 1980s. Simons said where it once stood is the core or centre of the main Penelakut town, which has been challenging for both researchers and the community. “That’s part of the emotional and spiritual stress caused by the fact there was knowledge of missing children buried on the landscape but without knowledge of specifically, in many cases, where they are.”

The Penelakut Tribe addressed the discovery in Kamloops in a July notice to members, referring to the work on Penelakut Island.

“Andrew and Eric are hoping to come back and continue the work they have started when it is safe to travel within B.C. Just needed to let all of our members know that we are working on this issue,” it said.

The Penelakut Tribe has not been speaking publicly on the discovery this week.

Children from southern and eastern Vancouver Island went to the Kuper Island school, as did some from the Lower Mainland, according to a UBC report on residential schools. Youngsters from close to 50 communities were taken there, the document said. According to Truth and Reconciliation Commission reports, in 1908, the Kuper Island school’s principal described the facility as “insanitary” and “ruinous.”

The Penelakut Tribe is holding a March for the Children in Chemainus on Aug. 2, along with healing sessions on July 28 and on Aug. 4.

Simons said there are plans for an upcoming meeting with Penelakut officials. “We will proceed from there.”

• The National Indian Residential School Crisis Line is available 24 hours a day at 1-866-925-4419 to help survivors of residential schools.