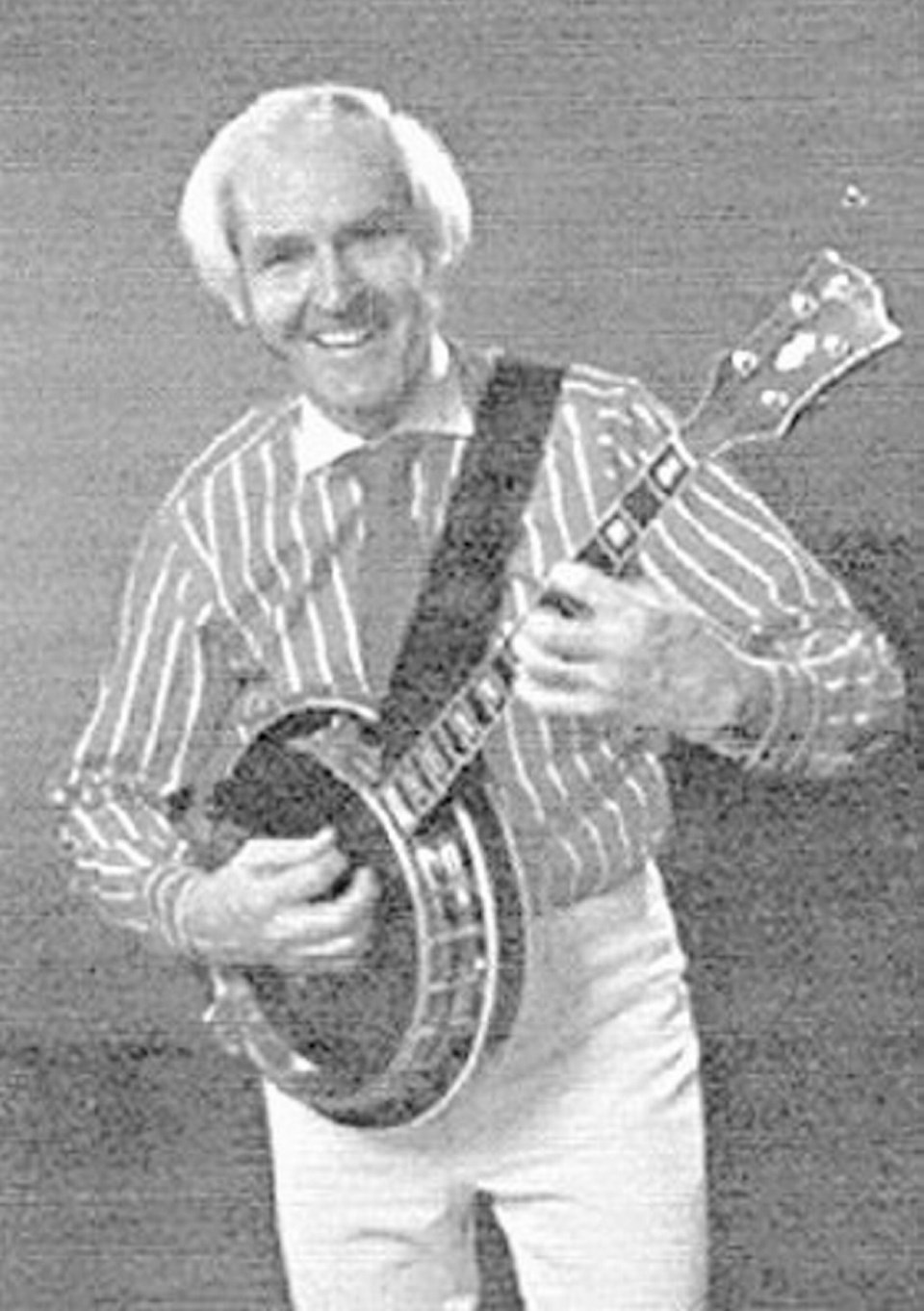

Borgy Borgerson was a 41-year-old Youbou logger when he was plucked from the bush to play banjo at Expo 67.

Half a century later, he was inducted into the American Banjo Museum Hall of Fame.

You probably didn’t know that when you passed him on the street. Victoria is full of people, mostly retirees, who quietly slip into town after leading fascinating lives elsewhere.

In banjo circles, though, he was a rock star — or at least a jazz star. Word travelled fast after he died Nov. 4 at age 93. “Anyone who has played Dixieland in Canada knows him,” says Toronto’s Ernie Mee, his longtime friend and bandmate.

Borgerson was born on Boxing Day in 1925. His real first name was Alfred, shortened to Fred, though Mee said the only people he ever heard use that name were Eunice — Borgerson’s wife of 70 years — and one bass player. Everyone else called him Borgy.

Borgerson grew up in a music-loving family of homesteaders in back-of-beyond northern Saskatchewan.

He got a banjo-ukelele at age five, and was playing guitar on stage with his fiddler father at nine. It was while listening to radio broadcasts of banjoist Eddie Peabody playing rhythm and melody at the same time that young Borgy got fired up about learning how to do so himself.

What he didn’t know, way back there in the woods, is that he was picking up an instrument that others were putting down.

The banjo was hugely popular in the early part of the 20th century. The instrument, particularly the four-string tenor version Borgerson played, was a staple of dance bands of the 1920s and 1930s.

But as dance bands morphed into Glenn Miller-sized orchestras and musical styles shifted, price and changes to amplification technology helped tilt the playing field (as it were) in favour of the guitar, which cost about a third as much to buy.

Nonetheless, Borgerson, who moved to Cowichan Lake to become a logger in the 1940s, remained entranced by the instrument.

For two decades, he’d toil as lumberjack during the week before swapping his chainsaw for a banjo at Friday- and Saturday-night dances — right up until the day he was recruited for a six-month gig at the Montreal world’s fair, where organizers wanted to feature a saloon-type band in a mock frontier setting. “Picture being at a logging camp on a Friday night and being at Expo 67 on the Monday,” Mee says.

Borgerson never did pull on his caulk boots again. He stayed back east after Expo, becoming a fixture of the night-club music scene in Montreal and then, as the Quebec separatist winds intensified, Toronto. He was not only a great musician, Mee says, but — these are separate skills — a great entertainer and a band leader with a professional approach to those who worked for him.

“He’d pay his musicians at the break and hope they came back,” Mee says.

Borgy and Eunice — Eunie to her friends — stayed in Toronto until 1993, when they “retired” to Victoria, though he was soon found playing at Hermann’s and other locales with the Dixieland Express. Another band, the 11-piece Belvedere Broadcasters, played 1920s jazz. He played jazz festivals around the Pacific Northwest and was gigging five days a week until two summers ago.

In September 2018, Borgerson was inducted into the banjo hall of fame in Oklahoma on the same day as Bela Fleck — the Jimi Hendrix of the banjo — and the late Jim Henson of Muppets fame. Poor health prevented the 92-year-old from attending, though. His health declined further after cancer claimed his son Larry in January. Borgy and Eunie had already lost a daughter, Diane, several years earlier.

Plenty of people had nice things to say about Borgerson at his celebration of life at the University of Victoria on Friday. Last to speak was a woman who told of once telling her Toronto jazz musician brother that she had just seen this great banjo player at Hermann’s.

“What’s his name?” the brother asked.

“Borgy Borgerson,” she replied.

“You have no idea,” her brother told her, “what a treasure you have there.”

No, we often don’t.