Niaz Hussaini had his legs blown off because he worked for our army, but he still couldn’t get into Canada on Friday.

That means the Afghan man couldn’t join his friend, Comox Valley’s Maureen Eykelenboom, at the charity bike ride she founded in memory of her dead son, the medic who saved Hussaini’s life.

And it meant Mike Rude, the retired soldier who had paid to fly his old friend here from California, was left at the Victoria airport with no one to greet.

To be fair, it was an inability to get paperwork done in time that stopped Hussaini from flying to Vancouver Island for a visit this weekend. But, his friends say, that paperwork wouldn’t have been necessary had Canada welcomed him as an immigrant a decade ago, as was the case with so many others whose ties to the Canadian military meant they could no longer live safely in Afghanistan.

Canada still won’t accept Hussaini, arguing the 33-year-old, his wife and five children are no longer in danger now that they live in the U.S. That upsets those who, like Eykelenboom and Rude, argue that we owe him.

“That’s a guy who lost his legs for our country, right?” said Rude, standing in the arrivals area of the airport. “He was serving with us and he got nothing from us.”

Rude befriended Hussaini in 2005 in Kandahar, where Hussaini, the son of an Afghan police colonel, was already working as an interpreter by the time Canadian troops arrived. It was in a May 2006 ambush that Hussaini lost his lower legs to a rocket-propelled grenade fired into his G Wagon.

He wouldn’t have survived were it not for the intervention of Andrew (Boomer) Eykelenboom.

“It was my son who saved his life,” Maureen said this week.

Reached by phone in California on Friday, Hussaini described what happened after the attack as he propelled his wheelchair out of the ICU at the Kandahar base hospital: “I see this tall, skinny kid with this big smile on his face. I said: ‘Do we know each other?’ He said: ‘I was your medic.’ ”

They hit it off. “I have so many wonderful memories of that guy.”

It was a couple of months later, on Aug. 11, that Andrew was killed by a suicide bomber in Spin Boldak. His death came just three days before his tour was due to end. He had already completed what was supposed to be his last foray outside the wire and had nothing much to do except pack for home when the call came in for a medic to join a patrol. He went.

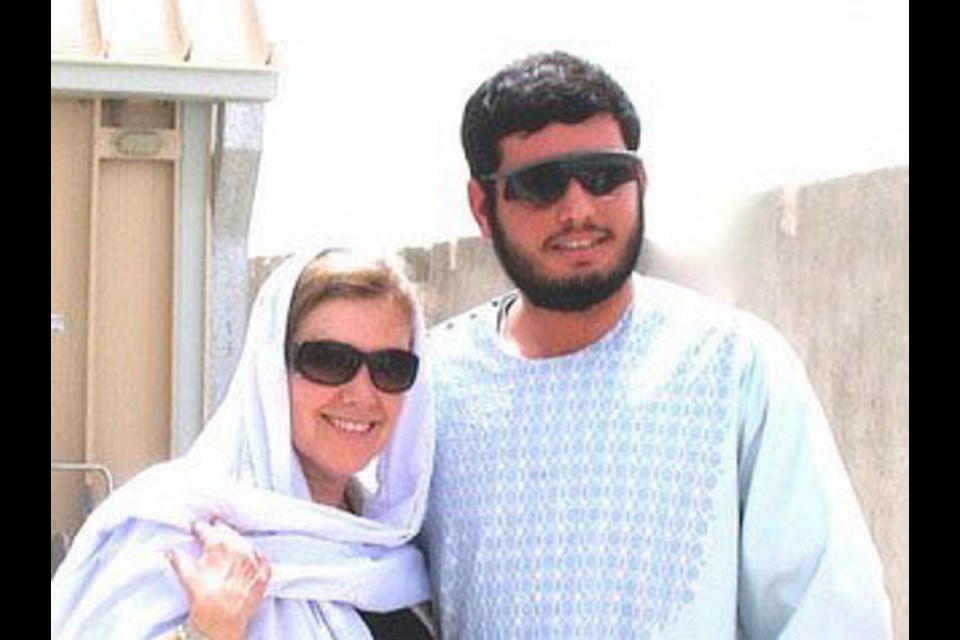

Hussaini kept working for the Canadian Army, and met Maureen when she visited Afghanistan in 2008. She has her son’s smile, he said Friday. “Very nice woman.”

They were to reunite at this weekend’s Boomer’s Legacy bike ride, which raises money for Canadian military members to distribute for humanitarian purposes. Cyclists will leave Comox for Nanaimo today, then make the return leg Sunday.

It’s disappointing that today’s visit didn’t work out, but what really bothers Hussaini and friends is the immigration question.

Beginning in 2009, the Canadian government allowed entry to Afghan interpreters who could prove they were in real danger because of their work for our army. (In November, Legion Magazine wrote of what interpreters who worked for Canada could expect from the Taliban. “They don’t finish an interpreter’s life with just a single bullet,” one told the magazine. “They torture interpreters to death.” The severed head of one interpreter was left on his chest on the Kandahar-Kabul highway.) By the time the program ended in 2011, several hundred interpreters and family members had come to Canada.

For some reason, Hussaini wasn’t among them. He still doesn’t know why his application didn’t get the green light. “I’ve been wondering about that question for the past nine or 10 years,” he said.

It’s not like he hadn’t been threatened multiple times.

After our soldiers left, Hussaini went to work for the Americans, who eventually did what Canada would not, flying him to the U.S. in 2017.

This is where he wants to be, though. “Canada is a better place for me and my kids.” Alas, immigration authorities rejected his bid to move here from the U.S. in 2018: “They said I’m in a safe country.”

Safe, but with a difficult life in which he and his family barely get by. His old Canadian Army friends sent a Walmart card to help clothe the children. His support network is here. Besides, Rude said, Hussaini had his legs blown off serving Canada, not the U.S. “It’s just not right that we’re not looking after Niaz.”

“The government isn’t looking after him like it’s looking after me,” Rude said. When Rude, one of many soldiers left battling demons after Afghanistan, needs help, he turns to the services offered by Veterans Affairs. “Who does Niaz have to turn to?”

Up in Comox, the woman who lost her son in the country to which the Hussainis can never return knows what she would like to see.

“I would bring them into Canada in a nanosecond,” Maureen Eykelenboom says. “They’re good people, the best kids ever.”