Anne Underhill was just 10 months old when her father was killed.

It would be another 80 years before the Oak Bay woman learned that he died heroically.

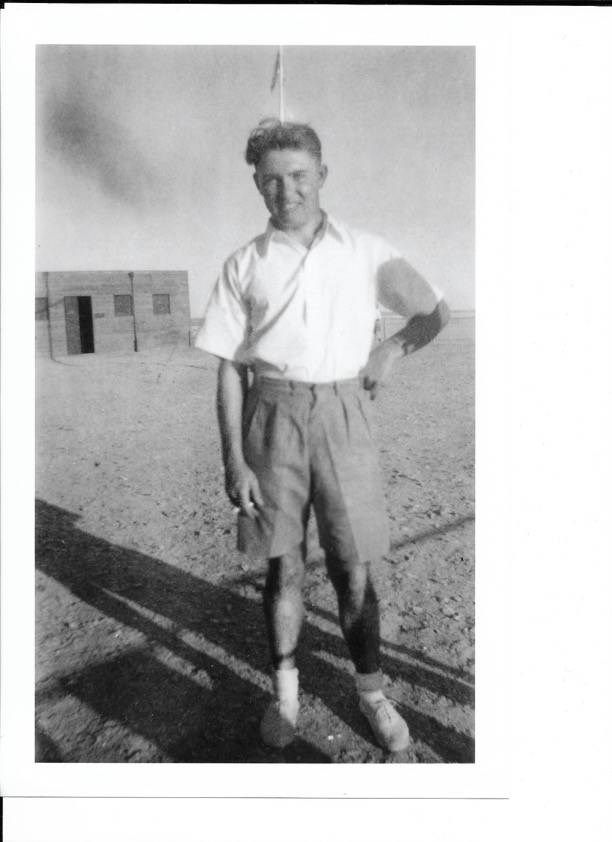

All Underhill knew growing up what that her father, Flight Lieutenant Robert Coventry, 27, was piloting a Bristol Blenheim bomber when it lost power and crashed near Gloucester, England in September 1940.

What she just discovered recently is that he stayed at the controls to prevent the aircraft from plowing into a school in the tiny hamlet of Quedgeley. And now that community plans to honour his memory.

Coventry was the grandson of the 9thEarl of Coventry and the son of the Hon. Thomas George Coventry, a charming, adventurous, Eton-educated Englishman who served as Conservative MLA for Saanich in the 1920s but whose love of gambling on horses caused grief.

Robert, born in 1913, attended Willows school and lived on Falkland Road in Oak Bay, where he was raised by his mother after his parents separated.

He was just 17 when, at the beginning of the Depression, he signed on with the Royal Air Force in Britain.

It was there that he met Underhill’s mother, whom he married in 1936. Underhill was born in Bath in November 1939, just after the Second World War began.

As a child, she would visit her father’s grave outside a pretty 15thcentury church in Down Hatherley, Gloucestershire, but really didn’t know much about his death, other than that it came after something went wrong on a training flight. “The bit about avoiding the school I knew nothing about.”

Frankly, she says, her circumstances didn’t seem all that unusual in those post-war years. “My mother was a widow, but there were a million widows in the U.K. bringing up their children.”

Eventually, Anne married Canadian journalist Jamie Underhill and moved to this country in 1970 (arriving in Montreal just in time for the October Crisis) before ultimately landing in Oak Bay in the late 1990s.

It was there that, in mid-February, she was stunned to get a call from the BBC, informing her of a move to recognize her father’s bravery. The broadcaster had interviewed 90-year-old Peter Hickman, who had witnessed the crash.

A woman named Helen Tracey, whose mother had been a six-year-old at the school, was pushing for a permanent memorial. Coventry was being hailed as a hero.

Underhill’s reaction? “Astonishment, actually.”

How did it make her feel? “Very proud.”

She has learned a lot since the BBC story aired, pieces being added to the puzzle. She heard how people in the area, which was dotted with airfields, could tell something was wrong as her father’s aircraft approached. “They were so used to planes coming and going that they could tell when things didn’t sound right.”

A maid in a nearby house rushed to the crash scene with a pair of shears. So did a farmer’s wife. Together, they cut the tail gunner out of the burning aircraft. Another crew member survived, too.

Coventry didn’t make it, though. His name is on the cenotaph at Cattle Point, along with that of his brother, Reggie, who also died while serving in the RAF during the war.

Steve Smith, the chairman of Quedgeley town council, says the story has had quite an impact in what is now a community of 26,000.

“Anne’s dad could have bailed,” Smith says. Instead, Coventry stayed at the controls of the stricken bomber, managing to steer it away from the school.

“Had he crashed in the school, those kids, maybe all of them, would have been killed,” Smith said. That means their children and grandchildren, the ones who live in Quedgeley today, would never have existed. That resonates.

So, what began as a simple plan to erect a memorial stone has grown into a more elaborate affair, with two local charities covering the costs. Accounts of the incident are being affixed to the walls of all five local schools so that students will grow up knowing about it.

There will be two services in September, one at the crash site and one at Quedgeley’s memorial garden, with a parade in between.

The current Earl of Coventry plans to attend. So does the daughter of one of the crewmen who survived the crash. “I would really like to go,” Underhill says, though she knows COVID-related travel restrictions put that in doubt.

But even if she’s not there, others will ensure that her father’s story — one that Underhill waited 80 years to hear — will live on.

“He will be remembered,” Smith says.