The irony, says Tim Hobbs, is that Ottawa directly affects the day-to-day lives of up-Island people way more than it does those city-dwellers whose voices carry loudest.

The irony, says Tim Hobbs, is that Ottawa directly affects the day-to-day lives of up-Island people way more than it does those city-dwellers whose voices carry loudest.

If your job touches salt water, or if you’re aboriginal, it’s hard to take three steps without the blessing of some far-off bureaucrat.

“We’re federally controlled individuals. Our rules are written in Ottawa. The heads of department are all in Ottawa.”

Hobbs is leaning on the sales counter of Redden Net, a Campbell River shop catering to all manner of mariners: commercial fishermen, boat drivers, sport fishing guides, ecotourism operators, hatchery workers, fish farmers, crabbers. …

All of his customers are wrapped in regulation by Fisheries and Oceans, or Transport Canada, or Aboriginal Affairs, or whomever, yet it’s the urban voices that have Ottawa’s ear. “Government works for them. It doesn’t work for a fisherman, or a tugboat operator, or a little oyster farmer.”

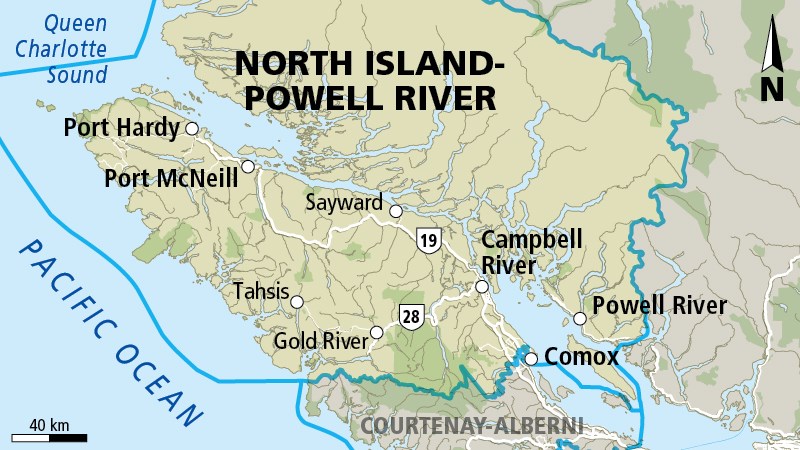

North Island-Powell River feels far from the centres of power. Once you’re past Campbell River, this is a wilder, more remote island than the tamed, uncalloused and Walmart-ed south.

It’s a hard-to-get-around riding, the bulk of it across the strait in an all-but-unpopulated expanse of coast sweeping north of Powell River. In area, it’s not much smaller than the entire Republic of Ireland.

The distant relationship with Ottawa was evident at a recent all-candidates meeting at the Thunderbird Hall on Campbell River’s Wei Wai Kum reserve. One of the common themes: Why are we always fighting bureaucratic entanglement and top-down, once-size-fits-all solutions from afar? Why do we have to resort to protracted court battles like the fishing-rights decision won by five Nuu-chah-nulth bands in 2009, but which the feds are still fighting?

The frustrations were not a surprise to any of the four candidates who attended, three of whom have aboriginal links.

The Green Party’s Brenda Sayers belongs to the Hupacasath First Nation and is the financial administrator of the Haahuupayak School in Port Alberni. New Democrat Rachel Blaney, executive director of Campbell River’s Immigrant Welcome Centre, had a grandmother in residential school and is married to the former chief of the Homalco First Nation. Conservative Laura Smith spent three years in Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada while working as a policy adviser for area MP John Duncan when he was minister. The fourth candidate, Liberal Peter Schwarzhoff, is a former federal government scientist who says the loss of environmental safeguards has left First Nations and others with little faith in Ottawa’s ability to protect their interests.

Duncan, a Conservative, has been the member of Parliament for Vancouver Island North for all but two of the past 22 years, but opted to run in neighbouring Courtenay-Alberni when the electoral boundaries were redrawn.

Transposing the 2011 results on the new boundaries results in a two-horse race in North Island-Powell River, the Conservatives outpolling the New Democrats 46 per cent to 42 per cent of the vote, with the Liberals and Greens trailing with six and five per cent, respectively.

Campbell River is home to almost a third of the riding’s 103,000 people. The city had its feet kicked out from under it five years ago when the Elk Falls pulp and paper mill, which once employed more than 1,500 people, was officially declared dead. That came on the heels of the loss of the TimberWest sawmill and 260 jobs in 2008.

Those blows were softened by the $1.1-billion reconstruction of B.C. Hydro’s John Hart generating station, which will continue for three or four years. This was a good year for tourism, too, but tourism jobs are seasonal. Housing prices have edged up since 2011, pushed in part by retirees who haven’t missed the fact that at $294,000, Campbell River’s median single-family house price was $50,000 less than that of the Comox Valley last year.

The new boundaries keep Comox and its Royal Canadian Air Force base (where Duncan announced a $30-million upgrade three days before the election was called) inside the riding but carve off the town’s Siamese twin, Courtenay. Comox has a population of 14,000. Ditto for Powell River, where the economy still relies heavily on Catalyst’s century-old, 440-employee paper mill (though note that the company just sold 600 acres of adjacent surplus land to a development company for $4.5 million).

It’s on the road to the northern tip of the Island that the reality gap with the urban world becomes more apparent: long stretches of lonely highway, road signs admonishing drivers to report poachers, bear-proofed garbage cans in the rest stops. Good luck getting a cellphone signal.

To steal a line from Cleve Dheensaw, there are two types of vehicle on the north Island: trucks and bigger trucks. The pulp and paper mills might be gone, the sawmills might be gone, but the logging trucks still pour out of the forest. This remains a resource-based economy. (It’s rocky, though. In Port Alice, word is that what was announced in February as a six-month shutdown at the Neucel mill — the village’s big employer — will extend until mid-2016.)

The First Nations presence is more pronounced in the remoter areas, too. Overall, nine per cent of the riding’s population is aboriginal (represented by a score of bands whose diversity isn’t always recognized in Ottawa) but in the north Island it’s closer to 20 or 25 per cent. The non-native population might fluctuate with the fortunes of the resource industries, but indigenous people have deeper roots. “We’re all here to stay,” says Nuu-chah-nulth vice-president Ken Watts, who is urging aboriginals to vote.

Overall, though, the population on the northern end of the riding has both fallen and greyed as young families chase jobs to the oil patch and elsewhere.

The shift is not lost on Nicole Reusch, a teenager who works in the Cable House Cafe in Sayward, a little village 70 kilometres north of Campbell River. Ask her about the election, she brings up a question that has been gnawing at her: How are today’s young people supposed to provide the taxes to pay for the care of Canada’s aging baby boomers? “It does feel a little like we’re being set up for failure.”

None of the parties have spent any time talking about that problem, though — or about many of the issues that really matter to young people in general or North Island-Powell River in particular. Reusch turns 18 — federal voting age — exactly a week before election day. Is there any point in casting a ballot for a kid from the end of the Earth?

Yes, says Hobbs, back in Redden Net.

“The system is not perfect,” he says, “but it cannot get any better if you don’t vote.”

> More information about the North Island-Powell River riding and its candidates