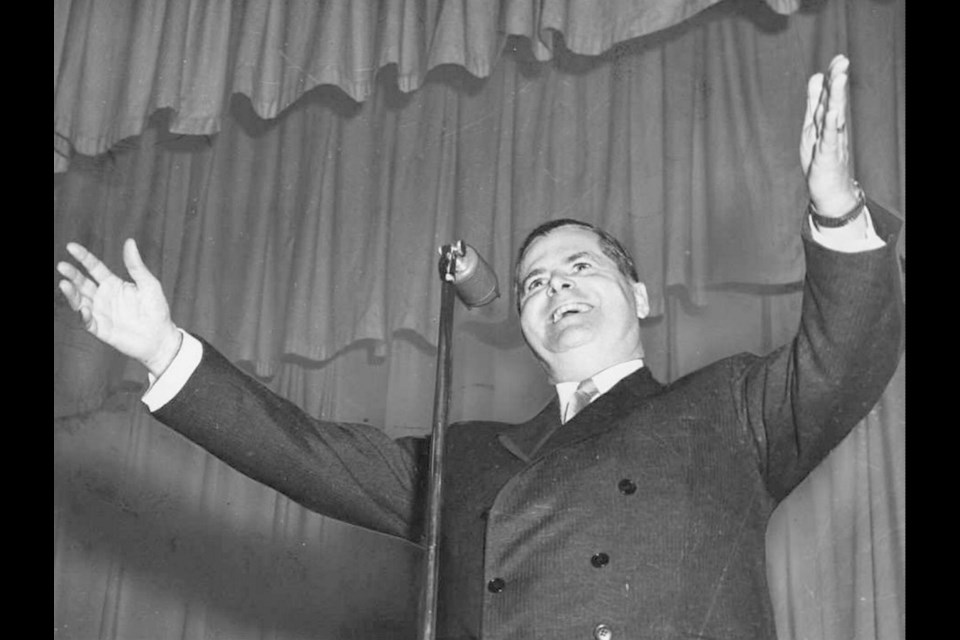

1952: W.A.C. Bennett

W.A.C. Bennett, a businessman from Kelowna, was elected to the provincial legislature as a Conservative in 1941, but twice his bids to lead the ruling party were rejected. Disgruntled, he resigned to sit as an independent in 1951, and then joined the Social Credit Party, which made a surprise breakthrough, forming government the next year.

Bennett was chosen to lead the party, and became the longest-serving premier in B.C. history, from 1952 to 1972.

“Campaigning on a shrewd populist platform of fiscal restraint, fervent free enterprise, anti-socialist zeal, western chauvinism and unrepentant Ottawa-bashing, he developed a chameleon-like ability to adapt policy to either and sometimes both sides of any contentious issue,” Vancouver Sun columnist Stephen Hume wrote about Bennett.

Bennett, who died in 1979, was known as Wacky to friends and foes.

1988: Brian Smith

B.C.’s first attorney general to resign over differences with the premier was Sir Richard McBride, who left James Dunsmuir’s government in 1901.

Brian Smith quoted McBride in his resignation speech in 1988, saying: “When Richard McBride resigned on a point of principle in the Dunsmuir administration in 1901, his father said: ‘My boy, resign everything but your honour.’… I am resigning as an act of honour.”

At the time, Smith complained Vander Zalm had a “fundamental misunderstanding” of the need for an independent attorney general in relation to two cases he was handling, including a legal investigation into one of the premier’s close friends.

“I had all kinds of threats around me that I should back off that investigation, but I didn’t. And as soon as that investigation was finished, I stood up in the house and resigned,” Smith recalled. “It was a terrible thing to have to give up the job you loved.”

He remained in the Socred caucus for more than a year, secretly trying to persuade enough backbenchers to leave as independents so they could force Vander Zalm out and reform the party. The ploy didn’t work, and Smith left politics to become the chairman of CN Rail.

Smith believes Wilson-Raybould will be given a rough ride if she tries to remain in the Liberal caucus, and predicts she has a bright future as a significant leader — but perhaps not one involving politics. “She is principled, and she ain’t no pushover. That is what the Trudeau government found out to their surprise.”

1988: Grace McCarthy

“Amazing Grace” McCarthy was the backbone of the Social Credit Party for decades, and became Canada’s first female deputy premier. But McCarthy publicly broke with then-premier Bill Vander Zalm in 1988, alleging political interference by the premier and his principal secretary in the sale of the Expo lands in Vancouver.

McCarthy quit her post as economic development minister as soon as the bidding was complete and set about trying to bring down Vander Zalm before he could fatally damage the party. She urged other cabinet ministers to resign as a way to weaken the premier. When Vander Zalm finally self-immolated in a scandal in 1991, McCarthy ran for the party leadership but was narrowly defeated by Rita Johnston.

1991: Gordon Wilson

Gordon Wilson was a master at changing his political spots, serving as leader of the Liberal party for six years, as a cabinet minister for the New Democrats, and the creator of a now-defunct new party.

Today, Wilson declines to discuss his past, but notes B.C. has several leaders, including Bennett, Vander Zalm and Dave Barrett, who built support for this province by picking fights with Ottawa.

“If I were to use a Western analogy, because of the polarized left-versus-right extremes in B.C., it is as if the majority of British Columbians are caught between two gunslingers on the main street of Dodge,” he told the Vancouver Sun.

“As spectators, we try to speak truth to power before the gunfighter who is fastest to the draw slays the other and governs from the saloon.”

Wilson assumed leadership of a moribund Liberal Party in 1987, with no elected members in the legislature. Nonetheless, he secured a spot in the 1991 campaign leadership debate and rocketed the party to prominence with one of the greatest sound bites in B.C. history.

As Social Credit premier Rita Johnston and NDP leader Mike Harcourt squabbled during the televised debate, Wilson interjected: “Here’s a classic example of why nothing ever gets done in the province of British Columbia.”

The Liberals elected 17 MLAs in 1991, placing second and effectively ending the Social Credit Party’s 39-year reign as the dominant political force in B.C. Despite his success, his time as party leader would end two years later when his extramarital affair with Liberal MLA Judi Tyabji was revealed.

Wilson would be deposed by Gordon Campbell, and he and Tyabji would form their own party, the Progressive Democratic Alliance. Wilson was re-elected in 1996 as the only MLA of the party.

Three years into his term, Wilson crossed the floor to join the New Democrats as a cabinet minister and assumed the finance portfolio after the resignation of Joy MacPhail. When Glen Clark resigned in a scandal, Wilson took a run at the leadership of the NDP, but aborted that mission.

He returned to the Liberal fold in 2016, when then premier Christy Clark rewarded him with a $150,000-a-year contract to promote opportunities for B.C. businesses in the liquefied natural gas industry.

1999: Joy MacPhail

Joy MacPhail resigned from her post as B.C.’s finance minister in 1999, when party leader and premier Glen Clark had become politically radioactive. Even when Clark himself resigned over his handling of a friend’s casino licence, MacPhail’s path to redemption was far from clear.

She cited “personal reasons” for quitting, in part because Clark’s hold on the party was so strong he could easily have shut her out even in his own disgrace. While she avoided direct confrontation at the time, she would later blast Clark’s ruinous style of governing. “I do not believe in confrontation as a standard way of doing business,” she said at the time.

MacPhail would later abandon her own bid for the party leadership to back Ujjal Dosanjh in order to keep Gordon Wilson — Clark’s chosen successor — from gaining control. Dosanjh brought MacPhail back to cabinet as labour minister the next year, but that government was short-lived.

In 2001, the New Democrats were swept from office, leaving MacPhail with one of just two NDP ridings in the entire province. She served her final term as the party’s de facto leader in the legislature.

2012: John van Dongen

John van Dongen, a one-time Liberal solicitor general, shocked British Columbia in 2012 when he defected to the tiny B.C. Conservative party, and on his way across the floor blasted premier Christy Clark and his former Liberal colleagues with a long shopping list of ethical violations. “What I believe people expect from political leadership are core values that include integrity and a genuine commitment to public service,” he said at the time.

Van Dongen was incensed when the Liberals wrote off $6 million in legal fees racked up by the Liberal aides accused in the Basi-Virk corruption trial ignited by the bargain-priced sale of B.C. Rail.

His former colleagues in the Liberal caucus were quick to savage Van Dongen as self-serving, nasty and self-aggrandizing. His tenure with the Conservatives lasted only a few months and he soon lost his seat altogether while running as an independent.