Lightning Rock is a sacred site to the Semá:th (Sumas) First Nation in the Fraser Valley.

Thousands of people could be buried nearby, including victims of two smallpox epidemics that decimated First Nations in the 18th and 19th centuries.

But it isn’t designated a provincial heritage site, because it slips between the cracks of heritage regulations.

“It’s not clearly been modified by people. Therefore, it doesn’t follow under provincial recognition as a heritage feature,” said archaeologist Dave Schaepe of the Stó:lo Resource Management Centre.

“To the province, that doesn’t qualify as a form of archaeological site. [And] outside of the individual cultural features or individual artifacts that were found there, they don’t recognize the intangible side of the cemetery, which is the field. ”

This is why when developer John Glazema purchased the site in 2011, the B.C. Heritage Branch said there were no issues with the land. Glazema spent three years planning a $40-million industrial development, and it sailed through the Abbotsford planning department.

“They said we were good to go, Glazema said. We had done third reading, everything was a bit of a formality. And then at one final public hearing, (a Semá:th elder) stood up, and it came to light there was a sacred burial ground at that site.”

Abbotsford declined to let the project proceed, and Glazema approached the B.C. government about buying the land and giving it back to the Semá:th.

“We had gone through the process with the Heritage Conservation Act,” Glazema said. “We had spent a significant amount of money doing traffic studies and engineering and all that kind of stuff. Had we known [about the heritage issues] at the get-go we could have made better decisions.”

But five years later, the province still hasn’t cut a deal.

“I’m not upset with the Natives,” Glazema said. “The Natives have the ability to claim this land. I don’t want to be digging up sacred sites. That being said, the province has to take responsibility for this. If this comes up and they want to protect these sites, then they have to write a cheque.”

Glazema wants to be reimbursed for the money he has put into the project.

“We just asked for the money that we have spent, not a penny more, and nothing for our time, he said. It was basically the hard costs. Right now we’re out close to $12 million.”

“[But] we’re not making any headway. We’ve had numerous meetings, but I believe we have people there who don’t have the capacity to make the decisions that need to be made. And everybody, the politicians included, keep passing the buck.”

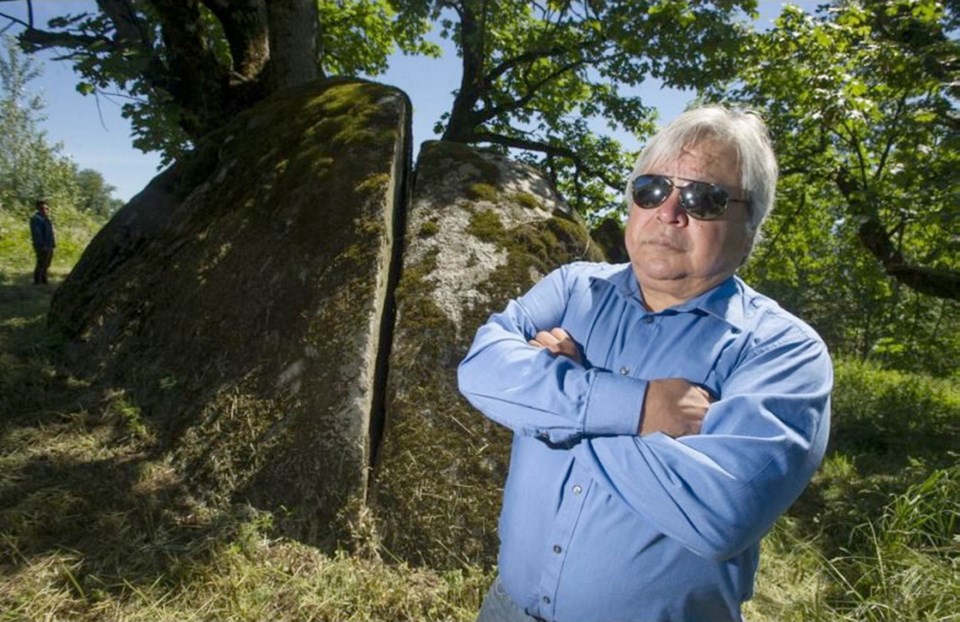

Chief Dalton Silver of the Semá:th First Nation echoes Glazema’s concerns. In 2017, the province signed a “memorandum of understanding” with the Semá:th to resolve issues around Lightning Rock. But two years later the issues have yet to be resolved.

“We’re almost there … with this site,” Silver said. “It seems the ministers, right up to the premier, all have said the right things and are talking the talk when we sit in the assemblies with leadership. But there seems to be a real hangup in the bureaucracy as to trying to actually achieve some of these things.”

On Friday, Indigenous leaders from across B.C., including former lieutenant-governor Steven Point, will gather at Lightning Rock to press the province to buy the land. Glazema will join them, in a rare display of co-operation between a developer and First Nations.

“What I’m worried about [is that] the government is looking to lowball this guy,” Silver said. “They are of the mind that he’s trying to rook the government for big bucks, and I think that he’s just trying to recover what he’s spent.

“But if that all goes awry, the Semá:th people on the heritage site are kind of left in the background. There will be no deal between the government and the guy who bought the land. And where will that leave us? Everything will be up in the air.”

Scott Fraser, B.C. minister of Indigenous relations and reconciliation, was unavailable for comment Tuesday.

In a statement, the province said it acknowledges “that Lightning Rock is a sacred place for Semá:th. We have had extensive discussions with Semá:th and the landowner, and we continue to work to find a solution to protect the Lightning Rock site.”

The site is on a bench on Sumas Mountain, directly above a historic Semá:th village that used to be on the shore of Sumas Lake. The lake was drained in the 1920s to create farmland.

The name Lightning Rock comes from Semá:th oral tradition that the rock was a shaman who got into a conflict with Thunderbird, a powerful creature in First Nations lore that lived in a cave up Sumas Mountain.

Thunderbird threw a lightning bolt at the shaman, who was split into the four pieces of Lightning Rock.