A pilot project in Vancouver is being expanded across British Columbia after more than double the number of drug-addicted people stayed in treatment to prevent them from fatally overdosing.

The initiative led by the B.C. Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS and Vancouver Coastal Health uses the same strategy that helped drive down the province’s HIV and AIDS rates and manage patients with other chronic conditions such as diabetes.

Dr. Rolando Barrios, the centre’s senior medical director, said a revamped system of care involves a team of doctors, nurses and social workers who take simple steps such as calling patients who don’t show up for appointments and work and addressing other needs such as housing and employment.

Island Health said that four Vancouver Island clinics are participating. These include the Rapid Access Addiction Clinic in Victoria, the AIDS Vancouver Island clinics in the West Shore and Nanaimo and the Health Connections Clinic in the Comox Valley.

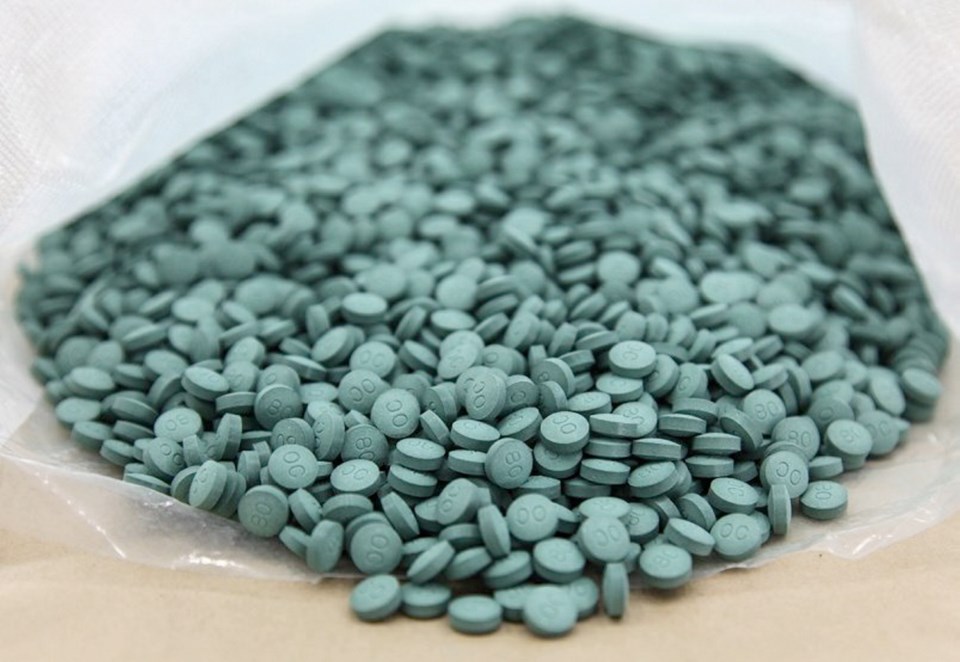

During Vancouver’s 12-month pilot project, 1,100 patients were prescribed suboxone, methadone or slow-release morphine to curb illicit-drug cravings and ward off withdrawal symptoms. After three months, seven out of 10 patients were still in treatment, up from three out of 10.

Barrios said retaining people who are addicted to opioids such as heroin and fentanyl in treatment is the biggest hurdle in the overdose crisis that has claimed 3,800 lives in B.C. from January 2016 to November 2018.

“We take for granted that people who are in treatment will come back to the office to renew their medication, then go to the pharmacy and pick it up,” said Barrios. “But we know that doesn’t happen.”

Suffering from drug use, mental illness of trauma, they might put themselves at risk of overdosing if they buy drugs from the street, he said.

The teams will remind patients when their medication is about to expire and have pharmacies connect with health-care teams when people don’t pick up their medications.

“We’re hoping that adherence to treatment will improve their overall outcomes and eventually, which we cannot document right now, will decrease overdose and mortality,” said Barrios.

People with opioid addictions tend of move a lot and migrate from place to place, he said.

“We’re actually creating a larger network of clinicians. So if my patients move to Vancouver Island, I know who to call to connect them,” said Barrios. “The whole idea is to keep them in life-saving treatment. We know suboxone and methadone actually prevent death.”

On Thursday, Health Canada approved Sublocade, which has the same active ingredient in Suboxone. It is taken once a month by injection.

“It’s still not here but there are really promising interventions that we need to get our teams ready to deliver,” said Barrios. “It takes an awful lot of time to come to the front line, for us to use it and treat people.”

Dr. Patricia Daly, chief medical health officer of public health for Vancouver Coastal, said lowering HIV rates involved setting targets to identify 90 per cent of patients in B.C. and keeping them on treatment.

“Most people who are dying are known to the health care system. They may even have started on treatment at some point in their lives but we’re doing a terrible job with retaining them on treatment, which probably needs to be, in some cases, lifelong or certainly for many years,” Daly said.

“We know that people with addiction relapse, that’s the norm, that it’s not necessarily a curable condition. They could be in long-term recovery but they need to stay on that treatment to prevent death.”

Guy Felicella battled a 20-year addiction to heroin and overdosed six times after fentanyl hit Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. He finally sought opioid replacement treatment that had him taking suboxone for nine months, starting in 2013.

“What that provided was stability so I wasn’t hell-bent on using fentanyl every day,” he said, adding he now works in the neighbourhood to help others in the same grip of addiction, alongside a nurse who once saved his life.