The Apollo 11 moon landing was 50 years ago today.

As Michael Collins orbited above, fellow astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin descended to the surface in the lunar module. Several hours later, Armstrong made his giant leap for mankind.

The Times Colonist asked readers for their memories of that historic day. Here are some of their stories, and we’ll run more in Sunday’s edition of Islander.

The South Pacific’s Niue Island was so isolated that Ted and Kathy Lewall didn’t see the Apollo 11 mission. There were no televisions.

They did get a preview, though.

“In May 1969, Apollo 10 flew a ‘dress rehearsal’ of the moon landing,” the Esquimalt man writes. The Lewalls, who were then living on Niue Island, were perfectly positioned to catch the end of that flight. “Our whole family were in awe as we looked to the west and saw a fiery ball traverse the breaking dawn sky, from the south to the north. The capsule was a flaming red-orange; occasionally a ‘spark’ appeared in the tail and lingered after the main fireball had passed.”

They feared the worst. “From our vantage point, it became obvious that no living organism could survive in that capsule.” Yet when they tuned in Radio American Samoa to confirm the bad news, what they got instead was a play-by-play: “We see the capsule.” “Now we see the parachutes.” “Splashdown.” “The hatch is opening.” “There is one head! And another! And another!”

“We were amazed,” Lewall writes, “that all had gone as planned, and that funerals were not being organized for the three astronauts.”

As a 22-year-old working for CP Air in Vancouver, Kathleen Martin toiled in a hectic environment, juggling the requests of reservation agents around the world. “It was an extremely busy office 24 hours a day with agents sitting on a teletype line and answering the telephone, processing the requests.”

The job was non-stop — except on July 20, 1969. “As the moment arrived, the telephone lines fell silent,” the Victoria woman says. “The teletype became still. Neither of these things had ever happened before.... No one, worldwide, took that time to book a flight with CP Air.

“My co-workers and I gathered around the black-and-white television and watched the historic moment. There was a feeling of reverence in the room as we all felt this human achievement. Then a few minutes after ‘the walk’ the phones started ringing, the teletype sprang into action and it was back to normal with one difference: A man had walked on the moon.”

NASA plucked Steven Toleikis’s engineer father Edward from RCA.

“For the Apollo 11 moon mission, Dad worked on the radios in the backpacks that the astronauts wore while exploring, as well as the moon buggy that was driven on the surface,” the Victoria man recalls.

“The day of the landing, our family gathered round the TV to watch the thrilling, historic moment of the first step, hearing Neil Armstrong’s voice, loud and crackling, live from the moon’s surface. Our dad was part of this!”

Every engineer who worked on the first Apollo moon landing was later given a memento: an Apollo 11 tie clip with a miniature lunar module. “I am wearing it (with my Star Trek tie!) on Saturday July 20, 2019,” Steven says.

The landlady at Barrie Bolton’s bed-and-breakfast in Bergen, Norway, translated the Norwegian-language commentary for the Victoria man and another Canadian as they watched the black-and-white broadcast over coffee and delicious apple cake. In return, when the voices from NASA’s mission control in Houston were heard, they translated Texan into English for her.

Serving with the military in Germany that summer, Larry Travis and a buddy watched from a small fishing village south of Barcelona, in a hotel with the only television in town. “The place was packed, with every man, woman and child sitting or standing looking at the not-so-clear 15-inch TV high up in on corner of the room. The people were mesmerized and talked in quiet whispers as if it were some form of ghost or God instead of a real person from planet Earth.

“We were pretty proud and for the only time during our travels were happy to be referred to as Americans.”

Saanich’s Dennis Minaker was living out of a backpack in P.E.I., picking strawberries by day, sleeping rough at night.

July 20 found him on lovely Cavendish Beach, where all were glued to their transistor radios. “Instead of beach-chatter we all listened to the live, moment-by-moment broadcast leading up to Neil Armstrong’s declaration ‘The Eagle has landed.’ It was a memorable moment on a sunlit afternoon, highlighted by a pale moon visible in the blue sky above.”

Victoria’s Paul Houlston and the other car hops were crowded around a small TV that someone had brought into the kitchen of the White Spot near Vancouver’s Stanley Park.

“There were very few, if any cars in the lot but one lone fellow drove in and ordered a hamburger. I told him that no one was going to serve him until the moon event was over. He said that he wasn’t interested and just wanted a hamburger.

“I remember being somewhat incredulous that someone would want to just eat a hamburger rather than watch this piece of history unfold.”

Registered nurse Linda Bitterman was working on the maternity ward at St. Joseph’s Hospital when her kid sister Donna came in to have her first baby that day. “Her husband, the fine military man that he was, was glued to the TV in the waiting room (along with their doctor). His thinking was that there would only be one first moon landing, but that he could always have more kids.”

The baby was born between the touchdown and Armstrong’s walk. The doctor got there just in time for the delivery.

“I took my little nephew into the nursery, gave him his first bath, then took him out for his debut. The staff tried to convince them to call him Apollo, but they resisted as Apollo Pahl didn’t sound like a great name to saddle him with.”

Victoria’s Ruth Marshall also spent the day glued to the screen — “except when giving birth” at St. Joseph’s.

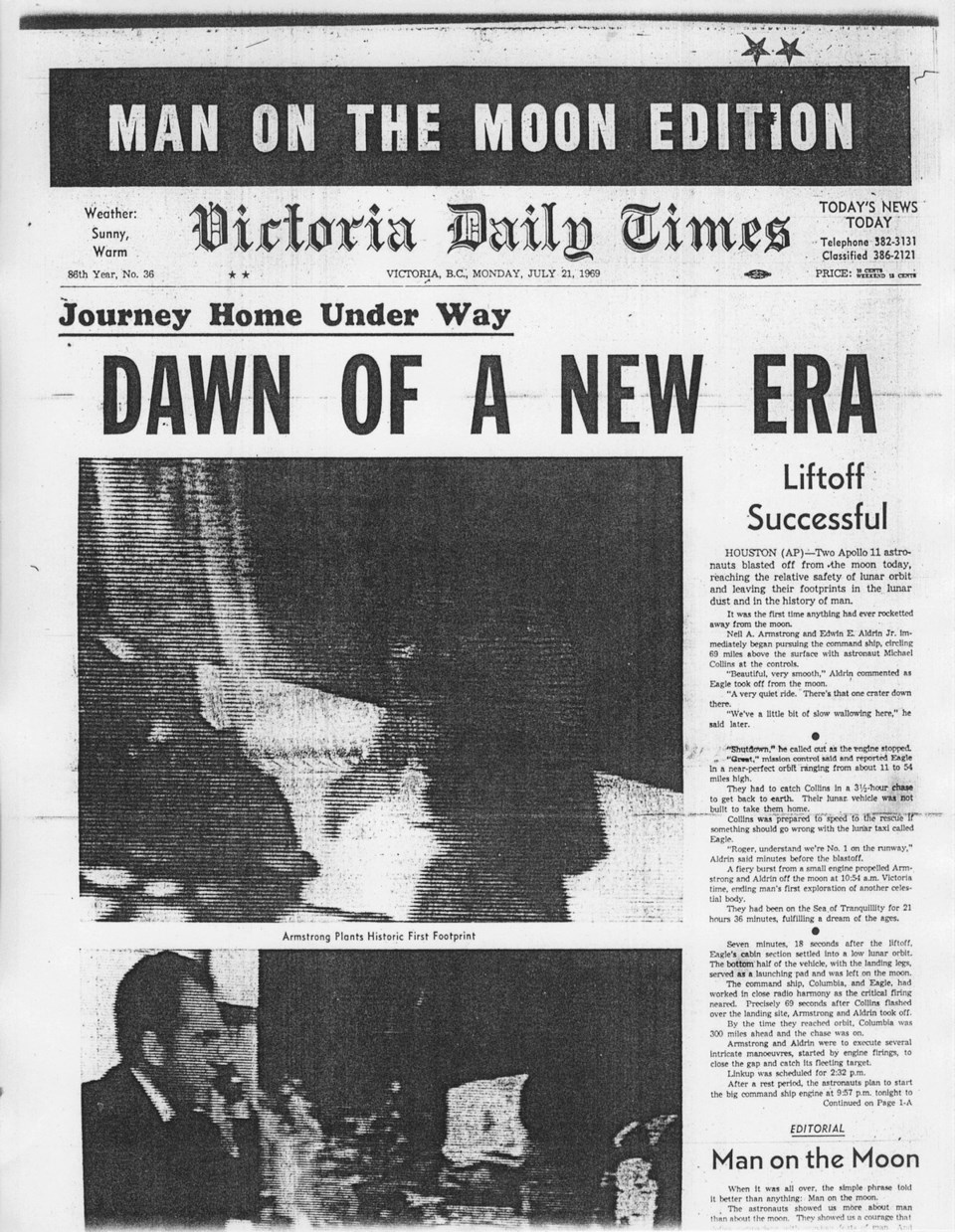

Marshall and her husband saved copies of the Daily Colonist and a commemorative booklet for their daughter.

“Although we lost Kory at age 17, she lived life to the full, leaving us with sweet memories of her life and the times in which she was born. All those commemorative papers are out on display as we remember those 50 years since her birth and the wonderful team who expanded our knowledge of this wonderful world.”

The news was so big that Nairobi’s Daily Nation published an updated, second edition. Francisco Moises remembers another refugee from Mozambique waving the newspaper around House Number 14 on Ngara Road while repeatedly shouting in Portuguese, “the Americans have landed on the moon.”

Having just arrived in Kenya from Tanzania after leaving Mozambique to avoid being forced into the Portuguese military, Moises could not yet read the English-language newspaper, but he could see the pictures: “I and other refugees milled around him to gawk at the photos of the astronauts bouncing on the moon, their feet hardly touching the lunar surface.”

It had lasting effect on the Victoria man. “The moon landing by Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins was a feat of great courage and an unbelievable scientific achievement. I was very excited while feeling dizzy because of the magnitude of the event which dwarfed me.

“The event changed me profoundly from being a boy overcome with a sense of hopelessness because of the earlier difficulties I had gone through in Tanzania. It convinced me that I too could overcome odds and triumph.”

In London, England, watching the moon walk meant staying up until the wee hours.

“We gathered in the landlady’s living room for hours waiting for those first steps,” says North Saanich’s Doug Row, who was 18 at the time. “There were many bleary eyes at work the next day, but that was not a problem because the bank’s customers were in no better shape.”

Ann Hadaway got up at 3 or 4 a.m. to watch the moon mission from her bedsit, a short distance from the 2,000-bed London, England, psychiatric hospital where the second-year nursing student lived. “It seemed so unreal, not only watching that hazy picture of Neil Armstrong taking those first steps on the moon, but also the fact that we were actually watching it in real time on television,” the Mayne Island woman recalls. “I think that made more of an impact on me than the actual landing.

“I made it to my 7 a.m. start at the hospital, but the rest of the day was such a contrast, dealing with patients so seriously ill with mental health issues who neither knew or cared there had been a moon landing, that by the end of the shift I was actually wondering if the whole thing had actually happened.”

Linda Jones sat her 10-month-old daughter in front of the TV in their Gordon Head home. “I told her that she wouldn’t remember any of this, but I was making sure she saw it nonetheless.”

As the moon landing played out on the television of her Tsawwassen home, Elaine Evans rocked her two-month-old son and told him what was happening.

“I took him outside to where we could see the moon, and told him that when he was 50 he would be able to tell everyone that he has seen the real man on the moon 50 years ago,” the Nanaimo woman says.

“I’ll be with my son this July 20, not holding and rocking him, but hugging him and sharing a happy memory of a momentous event.”

Not everybody got to watch history unfold.

Victoria’s Natasha van Bentum was a city-slicker living in a no-electricity, no-running-water cabin in Atlin, population 325, when her boyfriend was among the able-bodied men whisked away to fight forest fires in the nearby Yukon. That left her chopping wood and tending to a team of huskies.

“I heard about the moon landing two days later, when a visitor from ‘outside’ stuck a copy of the Whitehorse Daily Star on a store window.”

Janna Ginsberg Bleviss listened to the moon landing via short-wave radio in the rural part of Liberia, Africa, where she was teaching.

The reaction from her students knocked the Victoria woman back, though. “They all thought it never happened … or that it would disrupt the natural order.

“Even when one of the U.S. agencies came up-country to show a film on the landing, the students replied ‘fake news’ [today’s lingo].”

Nor were the Liberians the only skeptics.

“I’d just moved to London, England,” writes Saanichton’s Michael Rice. “I was still overwhelmed from seeing the Stones at the Concert in Hyde Park, so the moon landing was underappreciated.

“My thought at the time was that the whole thing was filmed on a movie set ranch, and I’d expected to see a shot of lunar landscape on a billboard that fell over, revealing cars streaming along a Nevada highway in the background, with John Wayne peeking out of a fake lunar pothole.

“OK, I was 21 and a bit cynical, but I’m not yet 100 per cent convinced.”

Nor were the Liberians the only ones worried about disruption of the natural order.

As Armstrong set foot on the moon, Pervez (Perry) Bamji sat in front of his Banbury, England, television and recited the Mah Bokhtar Neyayesh (literal translation: Great Moon Recital).

“I prayed that man, having made this achievement by reaching the moon (a planet which is so important to all our lives on Earth), does not destroy it in any way,” the Victoria man says.

Bamji is a Parsee Zoroastrian. Zoroastrianism, the world’s oldest continuously practised monotheistic religion, emphasizes the preservation of nature. “The sacred texts known as The Avesta emphasize protection of the Earth, sun, moon, fire, water, air, flora and fauna making it, in effect, an ecological religion.”

Having only spent a few months living and working in East Germany, Barry De Silva’s language skills weren’t that great. So when a crowd packed a square in the city of Erfut, their eyes glued to the illuminated text moving across a ticker-tape display mounted on the corner of a building, the 23-year-old Englishman had to ask a bystander what had them transfixed.

East German TV wasn’t showing the moon landing, he was told — remember, this was the heart of the Cold War — so people had to make do with this running written account.

“And so, like the rest of the crowd, I watched the scrolling text,” writes De Silva, who now lives in Cowichan Bay. “My new friend read it out aloud to me so that I could follow along. When the lander was reported as having safely settled on the surface of the moon, the crowd let out a big roar and a spontaneous prolonged round of applause.

“I noticed in among the crowd a few Russian soldiers, who were a common sight when off duty, and even they applauded when it was announced ‘The Eagle has landed.’ It seems that a tremendous human achievement can transcend all kinds of boundaries — technical, national, political and even linguistic.”

On holiday from his NATO base in Germany, Peter Pellow and family were setting up a tent in a campground near Venice when “an excitable group appeared wildly signally us to follow them to their campsite.” The Pellows did so, albeit warily, as this was at the height of the Cold War and the strangers’ car had Romanian plates.

“Soon we were surrounded by other campers, all of us watching the moon-landing events on their portable TV,” the Comox man recalls. “What a show, everyone enthusiastically cheering the moon landers in their own languages, occasionally looking up at the brightly lit moon on a beautifully clear night.

“When Neil Armstrong stepped onto the moon the applause from all around was fantastic, everyone cheering for the U.S.A. and centred on us as we were Canadians who pretty well shared the same place in the world, right?”

“An unforgettable night that my children — then five, 10 and 11 — have also retained in their memories. For me, it was an eye-opening experience that these East Bloc citizens were so genuinely supportive of our Western space accomplishments.”

In the coastal city of Durban, 17-year-old Peter Houghton was envious: “South Africa had no TV in those days and we were jealous of what the rest of the world was watching.”

“But it didn’t really matter,” the Victoria man says, “because we could still have that feeling of wonder that they had finally done it, got to the moon that we could see shining brightly in the night sky. It was unbelievable that humans were up there.”

Jim and Betty Hesser had just moved to Chile, where Jim was a young staff astronomer at the new Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, when the Eagle touched down.

“Because the astronauts were supposed to sleep after their late-afternoon landing, we went off for an early dinner at a Chinese restaurant,” writes Saanich’s Betty. “Throughout our meal, our young waitress was listening to a transistor radio held tightly to her ear. Mid-way through our dinner she approached to ask (in Spanish), ‘You are Americans, right?’ ‘Yes, we are; why?’ ‘Your countrymen are walking on the moon!’

“After hurriedly paying the bill, we rushed the five blocks back to our hotel, where we found all staff and guests crowded into the common room where the hotel’s single black-and-white TV was showing the grainy, but awe-inspiring, images of the first moon walk.”

Gillian Bloom and her new husband, tired from the journey from Canada to a new job in Peru, were being treated to a drink in Lima’s Gran Hotel Bolivar when she happened to glance at the television and see the pictures of the moon landing.

“The commentator was very excited and was talking very fast in Spanish. My Spanish was not fluent at this point so I could only just get the gist of what was said, but what was most frustrating was that I could almost hear the American commentator, but could not make out what he was saying.”

The pictures were amazing, though.

> Sunday in Islander: More moon memories.