Victoria’s Ryder Hesjedal is winning praise, deservedly, for gutting out the Tour de France on a broken rib suffered during a crash on the first day of the three-week race.

Victoria’s Ryder Hesjedal is winning praise, deservedly, for gutting out the Tour de France on a broken rib suffered during a crash on the first day of the three-week race.

But slipping a little under the radar was the accomplishment of former Victoria rider Svein Tuft, who rode into Paris in 169th place, dead last — putting him in an exclusive club, that of the Lanterne Rouge.

That puts him in select company, including, against all odds, that of an indefatigable octogenarian from Vancouver Island.

The Lanterne Rouge — named for the red light hanging from the back of a railway caboose — is the unofficial honour bestowed on the last cyclist to complete the sport’s most famous race.

It’s no booby prize. Rather, it’s a celebration of those who refuse to quit, who keep going even when the chance of individual glory has disappeared.

Each year’s Tour sees dozens of entrants fall away through illness, injury, fatigue or a failure to stay close enough to the leaders. The last rider across the line wins cult status among hard-core cyclists, is feted for finishing despite enduring more pain, more time in the saddle, than anyone else.

This year’s hero was Langley’s Tuft, a workhorse for Australia’s Orica-Greenedge team. At 36, he had already gained note as the oldest rookie to ever compete in the modern Tour. He also had the reputation as a rugged type, an outdoorsman with a penchant for disappearing into the wilderness for extended periods, a cyclist who long lived a spartan life in pursuit of the dream. (A few years ago, he gave a talk at Victoria’s Pacific Institute for Sport Excellence in which he noted that athletes often don’t qualify for government funding until they no longer need it.) Sunday, battered and bruised, he finished a race that 29 other starters didn’t.

“Good for him. I read about him. He’s a good rider,” says Tony Hoar. “He seems like an independent-thinking guy.”

Hoar, 81, lives in Mill Bay, where he is best-known as the engineering genius behind Tony’s Trailers, maker of everything from bike trailers to racing wheelchairs.

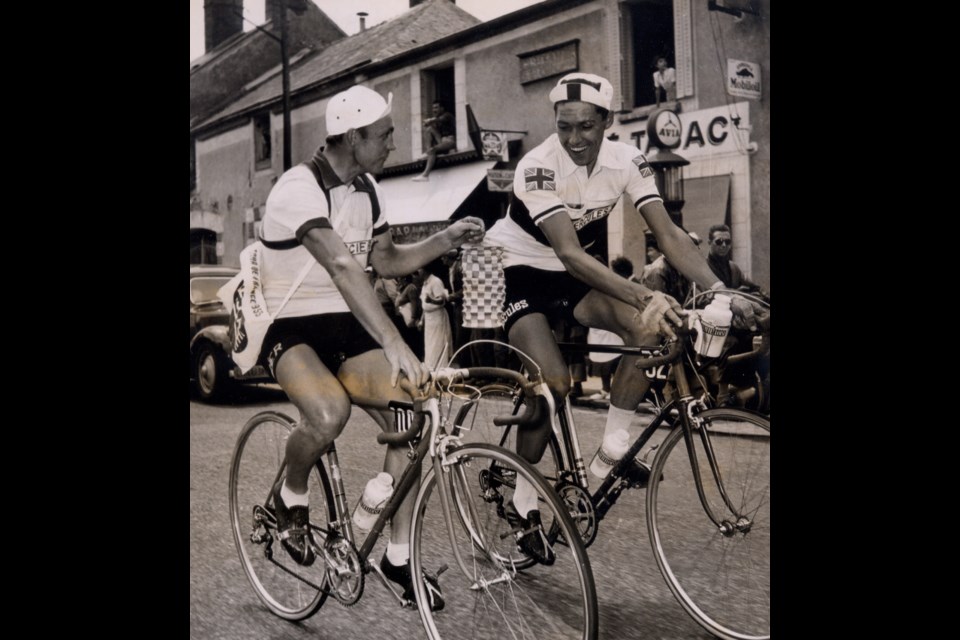

Lesser known is his past as the Lanterne Rouge of 1955, when he was a 23-year-old Englishman on the first British team to enter the Tour de France.

It’s strange to have two Lanternes Rouges with Island connections, particularly considering only seven Canadians, including the three who competed this year, have ever ridden the Tour.

It was a different sport in Hoar’s day. No helmets. No guard rails. No accepting food or water from cars. No radios to let you know where the other riders were; just pedal like hell and hope for the best. (“The radios spoil it for me,” he says.)

Ten riders set out on his team in 1955. “After nine days, we were down to two.” Hoar finished 69th overall, but 51 others didn’t finish at all.

It was brutally hard. Hitting gravel in a tunnel caused a high-speed crash. “There were no lights in the tunnel. Can you believe it?” The bike was OK, though, so he continued on, minus a good amount of flesh.

Sometimes, as he pushed his bloodied frame past the spectators, Lord Byron’s poem about a gladiator who suffers for the entertainment of others — “butchered to make a Roman holiday” — would pop to mind.

He still hears from racing fans who might have forgotten his other accomplishments, but remember his Tour result. A British journalist writing about Lanterne Rouge winners contacted him a while ago.

All living Tour finishers were invited to Paris to mark this year’s 100th version of the Tour, but Hoar stayed in Mill Bay. He followed the race in the newspaper, but doesn’t own a TV. Tony’s Trailers takes up his time. “I’m swamped,” he says.

Hoar was preparing to ship a couple of kayak trailers to the U.S. this week, was working on another for Switzerland and putting together a wheelchair for a kid in Pennsylvania. This Saturday, he plans to be in Victoria for the Tour de Disaster — part rally, part emergency-response exercise.

As ever, quitting just isn’t in the cards.

“I ride every other day. I go out for about an hour, just for fitness,” he says. “I still think I’m 39, until I get on the bike.”