A box of old photographs and passports sits in the basement. I bring the box upstairs. Sitting on the rug in the living room, I turn the box upside down and spread out the contents.

I find a picture of you from the door of your room in the residence for Alzheimer’s patients, in Surrey in 1991. Your smile is sweet but vacant.

I will never forget that once, when I was visiting, you had tears on your cheeks. This image haunts me. What were you remembering? What stories can the pictures tell me?

You were born in Victoria in 1917. Your ashes are sprinkled near the city of your birth, but Japan is where the pictures begin.

You’re three years old, sitting in a European-furnished room on the lap of your Obasan, wearing an ornate white dress with layers of lace on a flowing skirt. There is a large sash tied with a bow around your waist, a delicate necklace, a simple bracelet. Your hair is in the British style of a blunt cut with a fringe.

Next, I find a school picture from Glyn House Broadstairs School for Girls in England. You are about 11 years old and are wearing a simple striped school uniform with a low-slung belt.

How was it to go from your home in Japan to a British boarding school and holiday houses? You told me very little about this life. Were you lonely?

After you finished school in England, you returned to Japan. The pictures describe the British life abroad.

There are pictures of you in tennis whites, evening gowns, simple dresses at luncheons, draped over a sofa in an amateur theatre production. In some other pictures you are wearing riding clothes, or attending parties with more than 100 people.

In one, you are holding two small dogs in a lovely garden, wearing shorts and a halter top. A picture of a young Japanese man has the caption “Cook’s son goes to war.” Why does the family cook not have a name?

I wonder how your family treated your Japanese servants. I am both awed and appalled by the extravagant lifestyle.

In 1939, you married a Frenchman. I was told this was to the displeasure of my grandparents and that you were bored with the never-ending parties.

How beautiful you are in your wedding dress, white satin over chiffon with rhinestone buttons. You are carrying a simple bouquet of carnations and wearing a wide-brimmed hat.

Then, a picture of the Kamakura Maru that sailed from Yokohama to San Francisco. After, you travelled on to Chicago, New York, Paris.

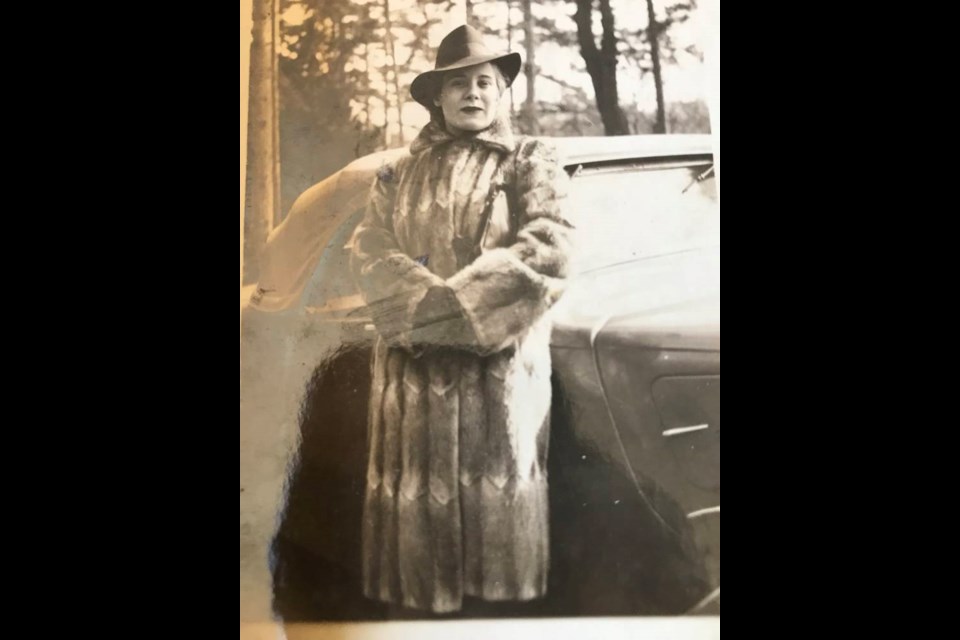

There are pictures of you wearing hats with feathers, hats with broad rims, alligator shoes and purses, furs, jackets with padded shoulders, wide-legged pants, diamonds, pearls, gold. Your life appears exotic. How did you feel about leaving Japan and moving to France? Did you have regrets?

I find a telegram dated Nov. 1, 1941: Famille Bonne Santé STOP Tous Bien STOP Presente Address Longy 254 Yamashitacho Yokohama.

You, my oldest sister and my father arrived in Japan in good health.

Japanese forces bombed Pearl Harbour on Dec. 7, 1941. For four years, there are no pictures. My family was taken to Karuizawa, an internment camp for foreigners. My second sister was born in the camp.

I know from reading stories about the internment that there was little food. The earth shook from bombs exploding nearby day and night.

Never have I understood why you and my father travelled to Japan when the world was so dangerous. You never spoke of this time. How did you deal with the fear for your children?

After the war, I was born in Switzerland and we moved to Canada. In a picture from 1950, you are in a house dress with a simple collar, a narrow belt at your waist, sensible shoes.

In 1962, at an expensive restaurant in Montreal, you are wearing a low-cut boutique dress, pearls, an exotic hat, and a mink stole. Your hair is dyed and permed.

I was a teenager concerned only with my own world. I wonder about your role as the wife of an executive. If we were to talk, I would ask you about your dreams, the challenges to rebuild your life in Canada, your role as a woman, whether you had nightmares from the war.

Then you moved away and I left for university. There is a picture of you at an elegant French restaurant in St Maarten in 1969.

You are wearing a long, flowing dress, sparkling earrings reaching almost to your shoulders, your white hair braided around the top of your head. You are so beautiful, like a radiant monarch butterfly warmed in the sun. Your letters told me you loved being part of Father’s new adventure of owning a restaurant in the Caribbean.

1975: rural Quebec. You are standing outside a double house trailer wearing rust-coloured polyester pants and a checkered shirt. Your world had collapsed.

How did you feel when the restaurant failed? Were you angry that you were back in Canada? I was far away dealing with my own life. I wish I had been nearby to share your worries.

For several years, there are only passport pictures as you moved from Canada to France and back again. Why did you go with my father as he chased his dreams? Did you want to have your own life?

I think of my own marriage and how hard it was for me to leave. Was it impossible for you? I wish we could share our fears, our joys, our regrets.

In 1992, my daughters and I sprinkled your ashes in the ocean off Vancouver Island, not far from where you were born. I packed your books and folded the Hermes scarves with your name written in indelible ink. I said goodbye to the mother I never really knew.

I put the pictures and passports back in the box. The question lingers. Why did I never ask about your life?

After moving from place to place all her life, Janine Longy of Victoria came full circle 10 years ago to live in the city where her mother and granddaughter were born.