The Spencer Mansion, now home to the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, was once inhabited by some of Victoria’s most notable families and served for a short time as British Columbia’s Government House. In his book about the mansion, Victoria’s Robert Ratcliffe Taylor describes the building and the families who once called it home — beginning, of course, with the founding family, the Greens.

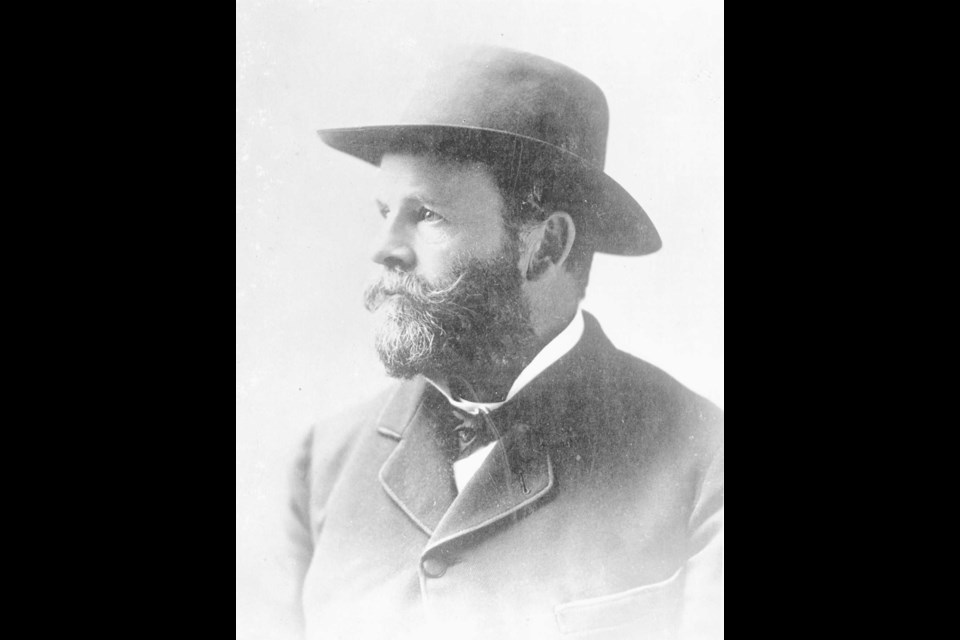

Alexander Alfred Green was born in England in 1833 in Ixworth, Suffolk. His father, William, and his grandfather were medical doctors. Young Alexander Alfred attended the Woodbridge grammar school and is said to have studied medicine with his father.

Around 1860, at the age of 27, he sailed from Britain to Australia in search of gold. Described as “a youth with a brilliant flair for answering when opportunity knocked,” he made a fortune in the Antipodes, and then went on to Nevada and California, where he joined Wells Fargo.

In the later 19th century, Victoria was a relatively short step away from San Francisco, linked more closely by geography and communication to that city than to the rest of Canada. The two coastal communities also shared some similarities. White settlements had begun in both places in peaceful isolation, only to be suddenly transformed by a gold rush.

When offered a post in Victoria, Alexander Green would have seen the similarities as well as the important difference: Victoria was British. After leaving California, he seems to have visited Victoria briefly, then travelled to England, where he married Theophila Rainer, before eventually settling in Victoria with his bride.

Alexander Green, with his wife and baby daughter, arrived in Victoria as a representative of Wells Fargo in late 1873, and his previous work experience won him a position as an accountant with Francis Garesche in the Victoria branch of Wells Fargo, which would eventually become part of the services of Garesche Green & Co., a private bank.

Founded in 1852, Wells Fargo Express employed the stagecoaches that became iconic symbols of the American West. The business had expanded to Victoria by 1860. The company established its local banking service in 1866.

Alexander Green used the fortune he had accumulated in Australia and Nevada to build (or maybe purchase) a house in the most attractive and fashionable residential neighbourhood of the city, James Bay, which was also home to Garesche, David Spencer, Emily Carr’s family, and, of course, Sir James Douglas.

In 1874, the Greens lived in a one-storey bungalow with a veranda at 15 Birdcage Walk, just east of the Birdcages, the first legislative buildings of British Columbia. (The Spencer family lived just across the street at the corner of Belleville and Birdcage Walk.) The house, which the Greens called Ferndale, sported wrought-iron decorative birdcages, replicas of the ones in Kensington Gardens in London. Emily Carr grew up a few blocks away from Ferndale and was best friends with Edna, the Greens’ eldest daughter, for many years. Carr describes life at Ferndale in the 1870s:

“The Greens were important people. Mr. Green was a banker. They had a lot of children so they had to build more and more pieces on to their house. The Greens had everything — a rocking horse, real hair on their dolls, and doll buggies, a summer house and a croquet set. They had a Christmas tree party every year and everyone got a present.”

The Greens lived at Ferndale until 1889. When plans for the new Legislative Buildings were being developed, they took the opportunity to build Gyppeswyk [Old English for “Ipswich,” the village in England where the Greens married]. In leaving the once-fashionable James Bay area, they were part of a trend: the Worlocks and the Spencers, among others, eventually forsook James Bay for the more spacious lots, better views and healthier air of Rockland.

Alexander Green was a typical 19th-century self-made man. He obtained his wealth and relatively high social position not because of any connection to the Hudson’s Bay Company or the Royal Navy, nor because he was in a profession needed by the colonial government. He did, however, qualify as a gentleman, an advantage that David Spencer did not have. Despite this leg up, Green could be said to have succeeded on his wits alone.

Once settled in Victoria, with the fortune that he had amassed in Australia and the United States, he achieved a social position that would have probably been impossible for a man even of his bourgeois background in class-ridden Britain. His new Moss Street home and its extensive property reflect his achieved social status, which was almost the equivalent of a country squire or gentleman farmer on a large estate in the Old Country. As on such properties elsewhere, Green’s estate had stables and a paddock for horses.

The Green family was conscious and proud of having achieved a social eminence they could not have attained back in Suffolk or Norfolk. This is illustrated by the size and opulence of the family’s monument in Ross Bay Cemetery. A large, gleaming, red marble pedestal dominates the Green family plot, which stands directly on one of the major carriageways, making a statement to any passersby.

Certainly, by the time of his death in 1891, banker Alexander Green had become, as his obituary observed, “a respected citizen.” He was what his contemporaries called a progressive, “go-ahead” businessman. By 1880, for example, he was one of the directors of the Victoria and Esquimalt Telephone Company, which established the city’s first telephone connections.

He was said to have enjoyed “popularity” and to have possessed a “positive integrity,” which no doubt enabled Garesche Green & Co. to prosper. He may also have indulged in land speculation because he applied to buy 100 acres at Bamfield Creek in 1882, and was co-owner of several hundred acres of the Nicola coalfields near Merritt.

Soon after his arrival in Victoria, Green joined the first congregation of the Reformed Episcopal Church. He was elected a warden. Throughout the 1870s, Green served as people’s warden and was active on the church committee. In 1887, he served on the local committee organizing the celebrations for Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee. He was also on the directing committee of the British Columbia Benevolent Society and was a director of the new Royal Jubilee Hospital.

As well, Green was co-manager of the bequest of John George Taylor (an Irish immigrant also affected by gold fever), who had set up a fund for the welfare of the city’s children. In this capacity, Green was, for a time, president of the board of directors of the Protestant Orphans’ Home (now the Cridge Centre for the Family) near the corner of Cook Street and Hillside Avenue, where he would possibly have crossed paths with David Spencer, who served on the board of management. Green was also a Freemason.

Alexander Green must have hoped to live another 10 or even 20 years beyond his allotted “three score years and ten” in what later generations would call his dream house. But, after suffering for several years from “an internal cancer,” he died in 1891 at the age of 58.

His funeral was an important local event that year. Between 300 and 400 friends and acquaintances personally called on his widow at the mansion to express their condolences. The funeral was “of more than ordinarily impressive character,” according to the Colonist, reflecting the opinion that Alexander Green was “a kind and sympathetic friend and a public and philanthropic citizen.”

Excerpted from Spencer Mansion: A House, a Home, and an Art Gallery, TouchWood Editions. ©2012 Robert Ratcliffe Taylor