The sailors, paddlers and rowers — no engines or support allowed — who set out on June 13 on the Race to Alaska’s first leg, from Port Townsend, Washington to Victoria, had to demonstrate when they registered for the race that they had the skill and experience and their crafts were seaworthy to survive the journey.

That day, they met a 30-plus-knot wind, a strong tidal flow rushing through the Strait of Juan de Puke-a, and standing waves with heights about equal to the length of the smaller race boats.

Four official rescues occurred in the race’s first few hours. One mast snapped, two vessels capsized and one did backflips in the heavy seas. Eleven teams didn’t finish within the first leg’s permitted 24-hour time frame.

The fun continued during the second leg, from Victoria to Alaska. Driftwood damaged hulls, medical emergencies took out crew members, sails ripped and more masts broke.

The winning team, sailing around the west side of Vancouver Island — thereby bypassing most of the driftwood hazards — won the race in about four days.

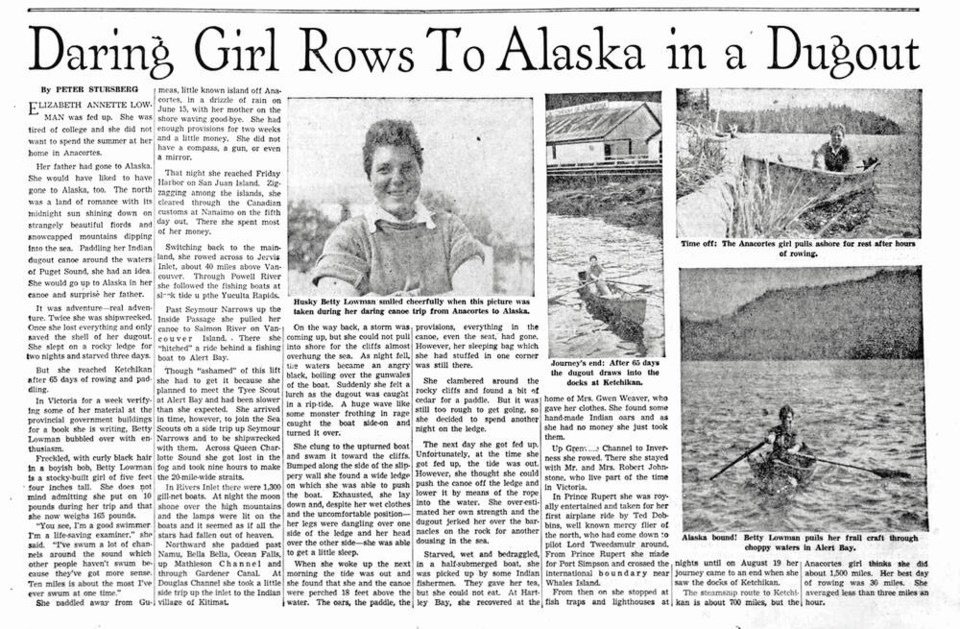

Contrast that to Betty Lowman’s adventure. In 1937, almost 85 years to the day before the Race to Alaska 2022 started, Lowman put in near Anacortes to row to Ketchikan in a 14-foot cedar dugout canoe.

“On June 15, four days after my father left for the north… I pulled away secretly from the north beach of Guemes Island, eagerly anticipating the surprise I should give him at Skowl Arm, Alaska,” her account in The Daily Colonist says.

Her father, despite setting her challenges to prepare herself, had told the 23-year-old he would never allow her to make the journey. Her friends and family warned her of grizzly bears, starvation, exposure, fog, getting lost, drifting to China, and so on.

But Lowman was young, unconvinced and confident that she could reach Alaska unharmed. So she snuck away.

Accompanying her for the first week was a friend who had prepared herself for the journey by being vaccinated for smallpox the week before, reacted badly to the vaccine and returned home.

Lowman wrote: “I had no money after the first two weeks, no compass, no gun, no mirror, no watch, and in the last two weeks I had only the hulk of the canoe and the sleeping bag.”

She also had minimal safety equipment — no location tracker, no VHS, no personal locator beacon, no duct tape and, at best, a 1930s life jacket. No Canadian Coast Guard was around to help her out, either.

Her expectations of B.C.’s coast were uninformed and romantic, drawing heavily on popular adventure books, film and radio series, such as those featuring Inspector Douglas Renfrew of the RCMP as a dashing, McGyver-like, prevailing-over-wilderness (Caucasian) hero. They also reveal prejudice and lack of knowledge that were common and accepted at the time.

“The vague picture in my mind of the island-dotted sea ahead had in it no people except mildly savage Indians and possibly American fishboats on the way north, no shelters, no bathtubs, no radio, no medical aid. But, yes, I did hope that somewhere along the way I’d meet a Royal Northwest Mounted Policeman, like Renfrew, out tracking down his man.”

Instead Lowman found dozens of busy communities, logging camps, fishing camps and hospital and fish boats and many kind people up the Inside Passage, all connected and up to date on news and current events by radio. She came to rely on them for hospitality, food, baths, comfortable beds and, sometimes, her safety.

Swamping several times on the journey, she lost everything but her life, dugout and sleeping bag in a gale and rip tide in Douglas Channel. There, she spent the next three days on a narrow ledge five metres up a cliff until the storm blew out.

When the weather calmed, she found a slab of cedar and used it to paddle out against wind and tide. That evening, she was rescued by a passing fisherman.

Lowman’s time to Ketchikan: 66 days.

She wasn’t the first person to use only muscle or wind power to travel from Washington to Alaska, but she may have been the first Caucasian woman to do so.

Twenty-six years later, she retraced her path, in her dugout, in the other direction.

keiran_monique@rocketmail.com