Leanne Rooney is trying to decide what to plant above her husband’s grave. Will it be a Douglas fir or a red alder? A big-leaf maple, perhaps, or a native shrub?

Three weeks ago, John Rooney was laid to rest in the Woodlands section of Royal Oak Burial Park in Saanich. The Rooneys are from Vancouver — so why was John buried on Vancouver Island?

Woodlands is B.C.’s only green burial site, and John was buried in a simple pine box, built with no nails, glue or varnish.

“We didn’t want to cause more pollution,” Leanne said. “We wanted to be a positive thing for the world, not a negative.”

She sacrificed proximity so that ethically and environmentally, her husband rested at a better place.

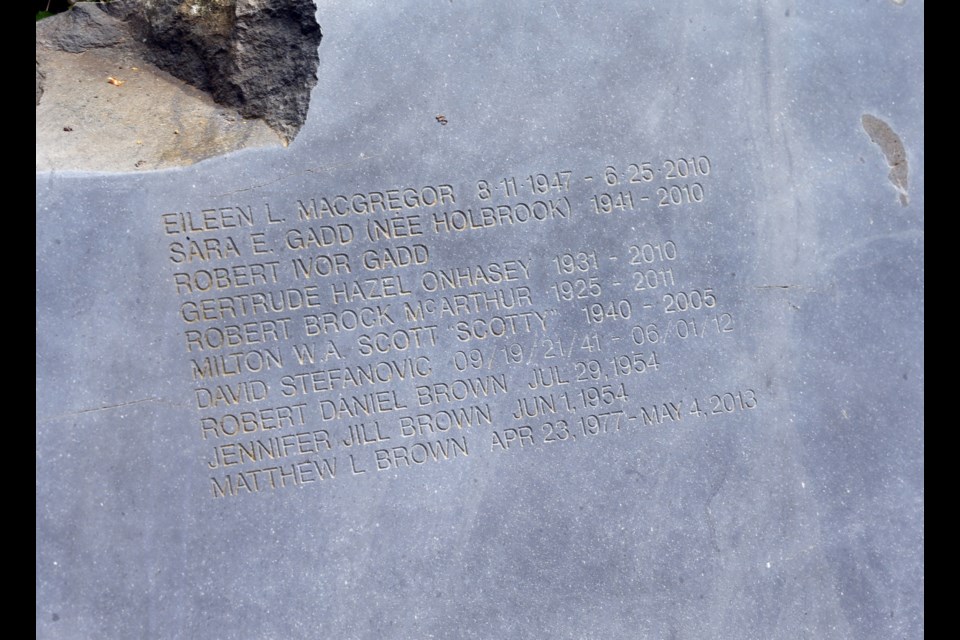

Her husband was the 102nd person to be buried in the quiet forested grove. Without the boulder memorials, it is hard to tell Woodlands is the resting place of more than 100 people, especially as recently planted trees and bushes mature and meld into the natural landscape.

“I can just imagine how beautiful it will be,” Leanne said. “It’ll be a very small footprint. There are no markers. I’m OK with that. I took GPS co-ordinates so I can visit him when I can.”

The Rooneys represent a segment of the population — environmentally conscious people who lived their lives green and are seeking greener alternatives in death — that is fuelling the growing popularity of green burials, forcing cemeteries to consider new approaches.

Typically, green burials ban the use of embalming fluids and concrete vaults. Bodies are laid to rest in biodegradable shrouds or caskets and in shallower graves to aid natural decomposition. Instead of individual markers, names are often inscribed on a common marker, or in some cases, no markers are used.

There have been 103 green burials at Woodlands since it opened in the fall of 2008. Another 83 people have prearranged their burials at the site. Plans are underway to expand Woodlands to two-thirds of an acre, doubling the current 254 lots to about 500.

Executive director Stephen Olson is so certain demand for green burials will increase he has committed to dedicating half of Royal Oak’s yet-to-be-developed 64 acres to natural burial in the future.

“That’s how convinced we are that this is going to be so widely adopted,” he said.

So far, green burials have been slow to catch on in Canada. Aside from Woodlands, there are three other green cemeteries in Ontario. In comparison, there are more than 200 green cemeteries in the U.K.

Contrary to predictions that green burials are a fad that will die out, many believe the back-to-basics practice is here to stay.

Michael de Pencier, director of the Natural Burial Association, is calling for a departure from modern burial practices, which with their granite or marble headstones and exotic-wood caskets can be expensive and wasteful.

“All this opulence is fairly recent, driven by the industry and society,” he said. “We have to get people to picture, what would you like when you die? Would you rather be buried under an oak tree or under a big slab of marble?”

The Ontario-based association is working toward raising awareness of eco-friendly burial practices, but also wants to push the concept further. So far, all green burial sites in Canada are attached to traditional cemeteries, de Pencier said. He would like to see the creation of natural cemeteries that become unprotected parkland.

Even though green burials are less costly than traditional burials — forgoing concrete vaults and headstones can cut about $2,000 from the bill — for those who opt to go green, it is never about the money.

“It resonates with them on a very philosophical or spiritual level,” Olson said.

About 90 per cent of people who choose green burials had previously expressed a preference for cremation, Olson noted. It suggests that even though green burials make up only a small fraction of interments in B.C., they could nibble away at Greater Victoria’s cremation rate, which at 90 per cent is considered to be the highest in North America.

Most people choose cremation over traditional burials because it is simpler and less expensive, and is considered to be more environmentally friendly. But cremation releases carbon emissions and mercury toxins from dental fillings into the air.

Of course, green burials are not new. In the past, most burials were green by necessity.

Over the last century, the practice was eclipsed by modern funeral practices with shiny caskets, formaldehyde in embalming fluid and manicured green lawns held up by underground concrete lining the norm.

But the tide seems to be changing.

Green burials are becoming very “au courant,” said Catriona Hearn of landscape design firm Lees+Associates, which designed the Woodlands area as well as many other cemeteries in B.C.

“Every municipal cemetery is talking about this,” she said. “Virtually every community doing cemetery planning is having to consider green burials. They may choose not to offer it, but they are talking about it.”

In Salmon Arm, the city’s conceptual plan for its new cemetery site include green burial “pods” in wooded areas, rather than clear-cut zones. On Denman Island, a group of residents has been working since 2009 to establish a natural cemetery on land protected by a conservation covenant.

But so far, the interest doesn’t seem to be translating to green-burial cemeteries — at least not yet. One obstacle is the uncertainty whether there is a sufficient market for it.

“No one really knows where it is going right now,” Hearn said. “It’s hard to offer it when they’re not sure about the uptake.”

Another obstacle, especially in urban areas, is the cost of land and geography.

The biggest hurdle, however, could be lack of public awareness.

The Rooneys first read about green burials in 2008 when Woodlands opened. Despite the distance, Leanne said choosing Woodlands for her husband was the right decision.

When she visited the site, she was struck by the natural setting and remembered thinking it will one day smell like rain-scented forests.

“It felt right this is where John would be,” she recalled.

“It was the most comfortable decision I had to make in this whole process of losing him.”