After 30 years of treaty talks, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission action agenda, and the adoption of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, First Nations still face racism on a systemic basis. Can Indigenous People ever find justice in this province?

John Price and Nicholas XEMŦOLTW̱ Claxton, co-authors in the new book Challenging Racist “British Columbia”: 150 Years and Counting, suggest that reconciliation will remain elusive unless the issue of Indigenous sovereignty is recognized as central and properly addressed. In this three-part series, the authors review how the 1871 Terms of Union that brought this province into Canada affected Indigenous peoples, how Indigenous people have fought for sovereignty before and after, and why new initiatives directed at recognizing and institutionalizing Indigenous sovereignty may be the only path leading to justice and reconciliation

The Cowichan and W̱SÁNEĆ Nations are fighting not only COVID but also COVID-related discrimination directed at members of their communities. Recent reports indicate that racism directed at Indigenous people is endemic in health care and many other sectors.

Is there a link between this racist present and our colonial past?

After researching and helping to write the new publication Challenging Racist “British Columbia”: 150 Years and Counting, we believe there is.

Though this province joined Canada in July 1871, preparatory discussion regarding the Terms of Union began much earlier. In March 1870, 21 white, male members of the legislative council of the colony of “British Columbia” debated and drafted terms for a proposed union of the colony with Canada. The draft terms omitted any mention of First Nations, even though Indigenous people constituted nearly 80 per cent of the population at this time.

To some, such an omission is not surprising — after all, this happened over 150 years ago. To expect more might easily be construed as “presentism,” of imposing today’s values on the past.

As it turns out, however, the Legislative Council’s erasure of “Indians” in 1870 was a wilful, vile act that was challenged even at the time.

The British colonial office appointed Arthur Musgrave as the colonial governor of “British Columbia” in the summer of 1869. His predecessor, Frederick Seymour, had been ill for some time and died suddenly in Bella Coola.

Musgrave’s instructions were to bring the colony then ruled from London into the Canadian federation, with the governor having an important role, since “the constitution of British Columbia will oblige the Governor to enter personally upon many questions—as the condition of Indian tribes and the future position of Government servants…”

Musgrave published his imperial instructions in the Government Gazette that fall and drew up draft terms of confederation that were submitted to the Legislative Council in early 1870.

Of the 16 clauses submitted for debate by Musgrave, a number touched on the future position of government officials, as suggested in his instructions, but not one referred to First Nations.

This omission did not go unnoticed and in the subsequent debate in the legislature on confederation, the New Westminster representative, Henry Holbrook, challenged the erasure. From the onset, however, he was met with fierce resistance.

When Holbrook declared he was bringing forward a resolution “with reference to the Indian tribes,” the attorney-general of the day, Henry Crease, tried to warn him off: “On a former occasion a very evil impression was introduced in the Indian mind on the occasion of Sir James Douglas’ retirement. I ask the Hon. gentleman to be cautious, for Indians do get information of what is going on.”

Holbrook persisted: “My motion is to ask for protection for them under the change of Government. The Indians number four to one white man, and they ought to be considered. They should receive protection.”

Crease: “These are the words that do harm. I would ask the Hon. Magisterial Member for New Westminster to consider.”

Holbrook wouldn’t let go, but the desultory discussion that ensued culminated in a vote 20 to 1 against his motion. So determined were the colony’s legislators to hide any discussion of Indigenous affairs, Holbrook’s motion was scrubbed from the official Journals of the Executive Council even though other defeated motions were reported.

Other than historian Jacqueline Gresko, few scholars have probed Holbrook’s opposition to the erasure of Indigenous peoples. Instead, some scholars have focused on this period as the beginning of representative government, compartmentalizing racism as something that affected others, while dwelling on the “liberalism” of the small white minority that was usurping power for themselves.

Sent to Ottawa, the draft terms adopted by the colonial legislature consisted of 16 articles and four supplementary resolutions — none of which mentioned Indigenous peoples or First Nations. Shortly afterward, the colonial governor Arthur Musgrave appointed three B.C. delegates to travel to Ottawa for negotiations with the Canadian government.

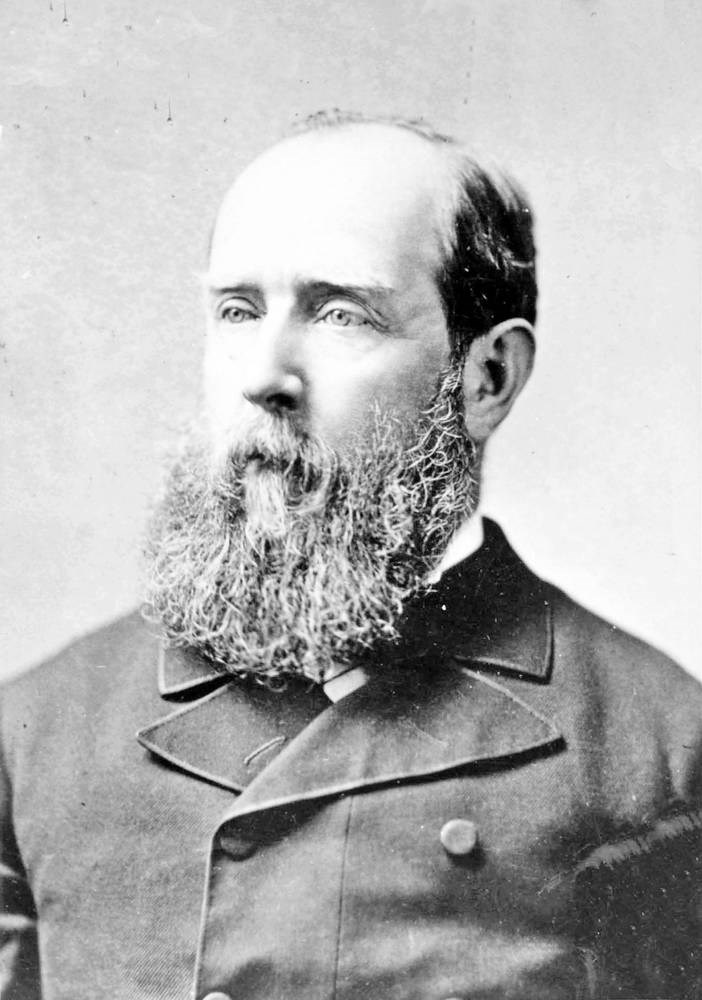

B.C. delegates Joseph Trutch, R.W.W. Carrall and J.S. Helmcken met with Ottawa cabinet ministers George Cartier (acting PM), Francis Hincks and Leonard Tilley with the goal of finalizing the Terms of Union.

Suddenly, on the last day of the talks, what became Article 13 of the Terms of Union made a dramatic appearance:

“13. The charge of the Indians, and the trusteeship and management of the Lands Reserved for their use and benefit, shall be assumed by the Dominion Government, and a policy as liberal as that hitherto pursued by the British Columbia Government, shall be continued by the Dominion Government after the Union.

Article 13 also specified that the B.C. government was obliged to hand over to the federal government land for reserves “of such an extent as it has hitherto been the practice of the British Columbia government to appropriate for that purpose.”

Who introduced Article 13 remains a mystery. Cartier may have suggested it since the British North American Act (1867) that governed Canada at the time specified that Indigenous affairs was a federal responsibility. But most historians point to the head of the B.C. delegation, Joseph Trutch, being responsible for the wording.

Unfortunately, Article 13 as a cure for erasure turned out to be worse than the disease.

In specifying that the federal government had to continue a “policy as liberal” as that of the B.C. government, and that the B.C. government only had to provide land for reservations to the extent it had in the past, Article 13 provided the B.C. government with a constitutional chokehold over Indigenous affairs.

It would allow the province to go rogue, refuse to recognize any form of Aboriginal title, refuse to enter into treaty talks, and to allocate the smallest amount of land for reserves in all of Canada.

First Nations have been fighting for justice ever since.

(Next Week: Part 2, “A Policy as Liberal as that Hitherto Pursued”)

John Price and Nicholas XEMŦOLTW̱ Claxton are co-authors with Denise Fong, Fran Morrison, Christine O’Bonsawin, Maryka Omatsu, and Sharanjit Kaur Sandhra of Challenging Racist “British Columbia”: 150 Years and Counting, available as a free download at https://challengeracistbc.ca.