John Ogilvy was a customs officer in 1865 when he was murdered trying to arrest a man for selling whisky to indigenous people in Bella Coola.

Four years later, his wife, Mary, writes a desperate letter imploring newly appointed colonial governor Anthony Musgrave for an extension to her pension. She is in poor health and caring for an eight-year-old child.

Mary’s letter, with a little note scrawled by Musgrave himself asking his secretary to look into the issue, can be read in the colonial government correspondence now made available online by the Royal B.C. Museum and Archives.

It’s just one of the gems to be found in about 90,000 letters, written between 1849 and 1871, the year B.C. joined Confederation.

Ember Lundgren, preservation manager at the museum, said the colonial correspondence is the largest amount of records the museum has ever put online.

Previously photographed and preserved on 75 reels of microfilm (a process completed in the 1970s), they have now all been preserved for easy access online.

And they contain countless clues, leads and stories for researchers and history buffs.

“There are all these interesting stories,” Lundgren said. “You start reading and think: ‘Oh, what is this all about?’ and you can delve deeper.”

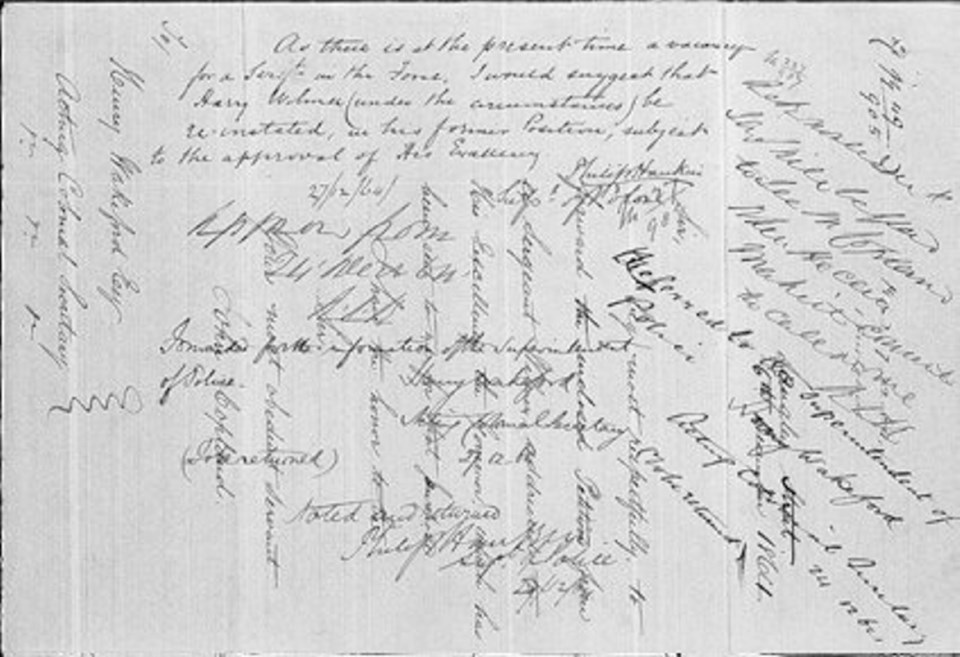

All the correspondence is handwritten, some more legibly than others. Also, letters are sometimes written over top of earlier letters. So a query might be written horizontally and the reply would be written vertically over top.

It is a sign, said Lundgren, how expensive and precious paper was in the 19th century.

From a professional archivist’s point of view, the task was complicated by a rearrangement move undertaken, for some unknown reason, in the 1920s and ’30s.

All the correspondence was rearranged alphabetically, according to last names of senders. Previously, it would have been arranged by government department and date.

But people can still search the digital database by name, for example “Smith,” and find pieces of a story. That’s the way details of the Ogilvy tale were revealed.

Lundgren said the museum collection has long contained an old, memorial photograph. It was set behind glass, encased in concrete and had once resided in the Customs Building. On its back, the photo simply had the name and a note: “Murdered May 6, 1865.

A search of the colonial correspondence, for the name Ogilvy, revealed the widow’s pleas.

Further searches of old newspapers revealed more of the story, including a $1,000 reward for the murdering whisky trader. He was Antoine Lucanage, widely known simply as Antoine, skipper of the schooner Langley.

“We were the Wild West back then, shootings, whisky-trading schooner captains, dead customs agents,” said Lundgren.

A researcher, or curious citizen, can also delve into correspondence from the two former British colonial governments, the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia. The records also include the period when the two colonies were united in 1866 as the United Colony of British Columbia.

A person can find letters from offices such as the commissioner of lands and works or the attorney general.

There are petitions for land-title transfers, or applications for contracts to build roads, even personal letters of introduction from people hoping to join the colony.

There are letters written by a settler to the colonial government complaining aboriginal people were breaking into his home and camping on his land.

Other correspondence reveals the settler was handed several acres previously set aside for First Nations people. But when the settler was made owner, nobody bothered to tell the original residents.

“It shows the colonial attitudes toward the First Nations,” Lundgren said.

It also shows the progress of the colonial administrations as they hired contractors to build infrastructure, such as roads and trails.

For example, one letter is from a man petitioning the government for $1,800 (about $28,000 in today’s dollars) insisting he is owed for beef supplied to feed the crews constructing the Cariboo Trail.

“It seems the people who were contracted to build the trail, for a large amount of money, too, weren’t paying their bills,” Lundgren said.

“There are all these interesting little details about infrastructure and how they constructed the early infrastructure and the early building of roads and things,” she added.

To check out the colonial correspondence, go to the museum website at royalbcmuseum.bc.ca, click on B.C. Archives and then click on Search Archive Collection. For a shortcut, type in “gr-1372” (including quotation marks) into the box marked “Browse.”

rwatts@timescolonist.com